For the purposes of this review, let’s accept two axioms. 1.) Nostalgia is both seductive and inevitable, and 2.) Explaining what was once funny is a sad, sad chore.

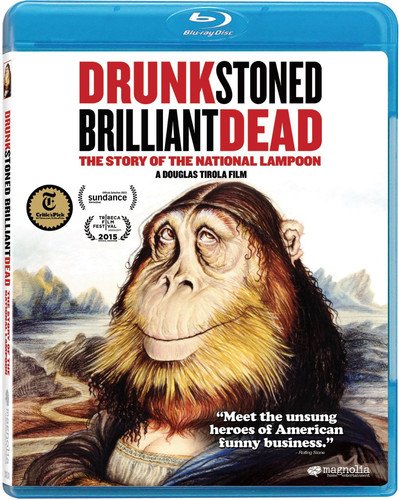

So by all rights Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead: The Story of the National Lampoon should be a bummer of the first order (as should this review, but hopefully you’ll keep reading anyway). Yet this talking-heads-plus-dirty-cartoons documentary, about the glory days and subsequent disintegration of the anarchic humor magazine, is better than it has any right to be. It often transcends its “Behind the Music” limitations to reveal the sources and inspirations for the vast majority of the comedy that’s amused, shocked, outraged and tickled us into submission for the last 40-plus years.

But Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead, directed by Douglas Tirola, is more than just an archeological dig through comedy history. The human element at its core is the story of Lampoon co-founder Doug Kenney, an unstable comedic genius who was often all three of the title adjectives and too soon (in 1980, at age 34) became the fourth, in ambiguous circumstances that still haunt his surviving friends and co-workers.

(Besides being a prolific writer/editor, Kenney played the dorky Stork in 1978’s Animal House, memorable for his line “Well what are we s’posed to do, ya mor-on?” and for hijacking a marching band and leading the instrument-toting lemmings down a blind alley.)

The film spotlights one of those comedy nexuses that coalesce every once in a while and then are fondly/ruefully remembered ever after: the Algonquin Round Table in the 1920s-30s, the Sid Caesar show’s writer’s room in the 1950s (with alumni including Neil Simon, Larry Gelbart, Carl Reiner, Mel Brooks, Woody Allen, etc.). More recently it’s the comedico-industrial complex centered on Jon Stewart and The Daily Show.

But in the 1970s the highest-grade humor was manufactured by the explosive issue-full at the National Lampoon, shoving a sharp (but extremely funny) stick in the eye of everything that anyone had ever held dear. Replete with sex jokes, drug jokes, gross-out humor, savage political satire and just plain craziness, it perfectly fit an era when the confluence of Vietnam, Watergate, rock & roll and the baby boomers’ coming of age created an insatiable desire to say the formerly unsayable and slaughter as many sacred cows as could be rounded up and shoved into the slaughterhouse.

You can see both the direct and indirect influence of the Lampoon just by the film’s roster of interviewees, who include Chevy Chase, Judd Apatow, Simpsons producers Mike Reiss and Al Jean, mockumentary titan Christopher Guest, P.J. O’Rourke, Tony Hendra, Christopher Buckley, Anne Beatts, and Animal House director John Landis and actors Tim Matheson and Kevin Bacon, just to name a few.

For those interested in the nuts and bolts of how a literally sophomoric humor magazine became a multi-media phenomenon, encompassing stage shows, comedy albums, a nationally syndicated radio show and a series of blockbuster movies, there are business guy Matty Simmons and publisher Jerry Taylor, the quasi-grownups who turned foul-mouthed hilarity into an actual moneymaking business – at least for a while.

It should be noted that the Lampoon was also a product of its time in that its creators were almost exclusively white males, that its frat-house humor was frequently demeaning to women and gays, and that it used/abused every available racial, religious and national stereotype in pursuit of guffaws. This paragraph has been brought to you by your local chapter of the P.C.F. (Political Correctness Foundation).

The film also includes heartbreaking (though very funny) archival footage of stage shows and radio recording sessions, featuring performing geniuses gone too soon (John Belushi, Gilda Radner) and recently lost (Harold Ramis). Were any of them – were any of us – ever really that young and seemingly indestructible?

As for Doug Kenney, Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead doesn’t simply blame his demise on the effects of too much money and too much cocaine, though neither one helped. Even before he lit out for Hollywood’s hills of white powder, Kenney’s mental state could be precarious – he had previously up and “disappeared” for months at a time, leaving colleagues very much in the lurch. If there’s a fault in the film, it’s that we don’t get a true sense of the demons that drove Kenney to both insanely comedic highs and irretrievable lows (his hiking death in Kauai might have been a suicide, a drug-hazed accident, or some ghastly combination). This is history told by the survivors, who have been either lucky enough, or belatedly sober enough, to tell the tale. Even had he lived, Kenney probably wouldn’t have been able to explain himself adequately – but it would have been fun to see him try.