Anyone not familiar with the family name of Band within the halls of the B movie archives probably shouldn’t be perusing such a vault in the first place. For today’s trash lovers, the formidable Band forename is Charles. If you still don’t make the connection, Charles Band is a feller who not became a major player back in the early days of home video sleaze (see: Wizard Video), but who has been cranking out one cheap ‘n’ cheesy exploitation movie after another in recent years. But long ago, when Charles was but a wee lad, his filmmaker father Albert was already hard at work making low-budget flicks for audiences to enjoy – albeit in a time when a strong sense of morals were still mandatory in movies.

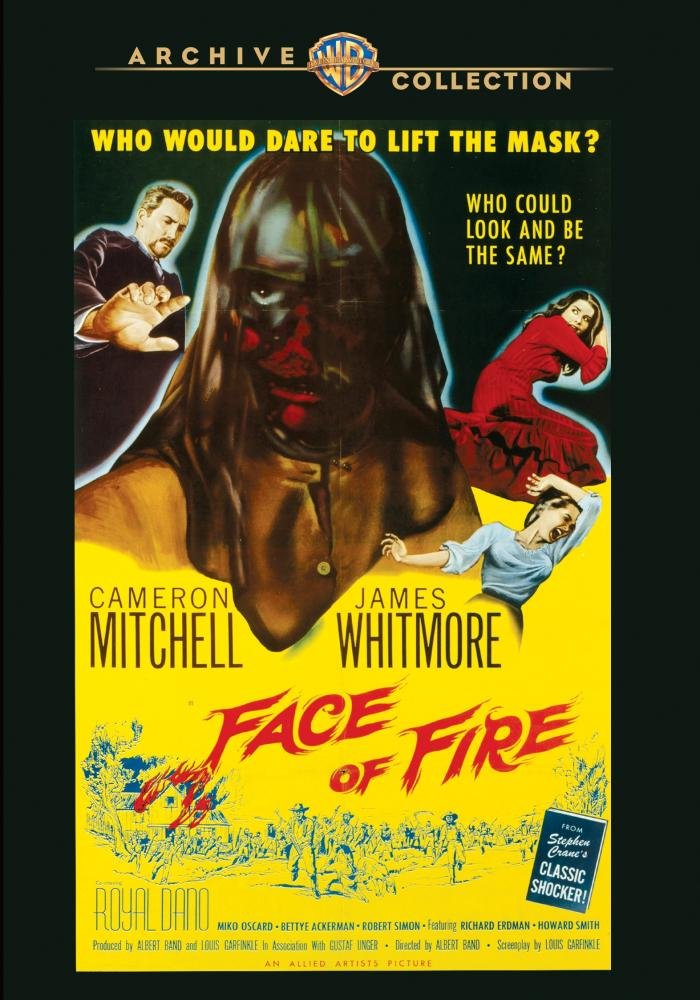

After making one of his best-known titles, the creepy 1958 ditty I Bury the Living, Albert Band moved to Sweden, where he continued to build up his legacy. It was during that very next year that Mr. Band directed another low-budget entry into the world of film: Face of Fire, which he co-wrote and co-produced along with the assistance of Louis Garfinkle, writer of The Doberman Gang and co-author of The Deer Hunter (a movie that anyone – B movie archivists or otherwise – should be well aware of), to bring us a surprisingly effective drama based on Stephen Crane’s short story from the very tail end of the 19th century, The Monster.

While rather slow in some parts, Face of Fire is nevertheless a very poignant tale that benefits from some downright atmospheric moments. In fact, you could even classify the Allied Artists presentation as an uncredited precursor to both The Twilight Zone (which premiered two months after the release of Face of Fire) and The Outer Limits. And while it is as far removed from the sort of output the Band Family would bring us come the late ’70s and beyond (especially the direct-to-video fodder we see hailing from Charles Band today), Face of Fire also has a few moments that no doubt inspired several slashers movies from that gloriously bloody era of ’80s horror offerings.

Also of note here is a glimpse of the great Cameron Mitchell on the final voyage of his initial career as a serious leading actor in Hollywood. After this, the late cult hero would begin his second wave of filmmaking: appearing in many an Italian gialli and pepla before descending into the very sort of B-grade horror, sci-fi, and exploitation movies that the Band family name is best-associated with today (although even Mitchell’s worst films are still light years above the Evil Bong series). As such, in Face of Fire Cameron Mitchell is still giving it his all, just as he had done a few years before in what was perhaps his last legitimate American starring role, Monkey on My Back.

Taking place in a small rural American town near the end of the 19th century (right before the whole nation went nuts over that whole Y1.9K thing, no doubt), the story finds Cameron Mitchell taking a backseat to his co-star, James Whitmore, for the first part of the film. And that’s only so we can establish Mr. Whitmore’s character – Monk Johnson – through and through. Revered by the men of the community, idolized by the children, and the object of every woman’s secret desire, Monk is very much a man’s man. When he isn’t working as stableman/caretaker for the prestigious Dr. Trescott (Cameron Mitchell), Monk is out taking the neighborhood boys fishing during the day, and wooing the eligible ladies in town at night.

Sadly, Monk’s days as a man are limited. When a fire breaks out one fateful night in the good physician’s residence, our heroic handyman successfully rescues Dr. Trescott’s son, Jimmie (Miko Oscard), from being consumed by the flames. Unfortunately, Monk himself is rendered unconscious during the feat; his noggin falling directly under the dripping acidic compounds housed in the local practitioner’s laboratory. Thus, Monk is given a Face of Fire – coming dangerously close to being The Man Without a Face thirty-four years early, while beating his cinematic cousin Edith Scob to being Les yeux sans visage (or l’œil sans visage, as it were) by nearly seven months.

The acid not only destroys poor Monk’s handsome face, leaving him to resemble the Jason Vorhees and Crospeys of the world (and once you see Monk wandering through the woods, his face covered with a black cloth, you’ll note how much more spot-on that assessment is), but it also decimates his skilled grey matter as well, leaving him with a mind of mush. Ever thankful that Monk risked his very life to save his son, Dr. Trescott takes to tending to the gentle giant in seclusion. Meanwhile, the townspeople – the very same men, women, and children who previously admired Monk – begin to malform into the very fearful, frightened, judgemental hypocrites you’d expect them to become after an ordinary man falls from their “grace.”

Like I said, it’s a fairly slow feature. But it’s definitely of interest to any fan of old school drama and/or horror (it could very well have served to mold the misshapen face of film in the years to come). Royal Dano – a distinguished character actor who would work for director Albert Band twice more decades later (including Ghoulies II, which should give you an idea of how things changed) – plays one of the villagers determined to do something about their resident freak of nature. Lois Maxwell, best known to audiences as the original Miss Moneypenny in the James Bond franchise, co-stars as Dano’s cruel heartless wife in a role that will have you yearning for Monk to become a hooded killer just so he can give her what she deserves).

Also starring in this filmic curio are Bettye Ackerman, a young beauty of film and (mostly) television whose final appearance would be in Albert Band’s direct-to-video Prehysteria! 2 in 1994 (as co-produced by Albert and his son Charles); Robert F. Simon (the moving picture industry’s first J. Jonah Jameson) as the local judge; current Community volunteer Richard Erdman (who discusses this film in Tom Weaver’s A Sci-Fi Swarm and Horror Horde); Howard Smith (also in I Bury the Living) as the sheriff; as well as the likes of Robert Trebor and Charles Fawcett – the latter of whom would stick around to in Europe to crank out a few pepla and exploitation flicks.

Erik Nordgren, the Swedish composer who would write the score for seventeen of Ingmar Bergman’s films, including The Seventh Seal and The Virgin Spring – the latter of which would one day be transformed into the rural exploitation horror classic, The Last House on the Left – lends his talent to the music department here. An essentially unknown crewmember named Edward Vorkapich (whose only other credited work in a feature film was Band’s I Bury the Living) served as cinematographer, and his (seemingly) amateur skills pay off quite well in giving the film a lot of its atmosphere, which – again – seem to pave the way for the world of B movies to come.

Never before released on home video (legitimately, that is), the fascinating – and shockingly moving – horror/melodrama hybrid Face of Fire finally finds its way to DVD thanks to the Warner Archive Collection. Presented in a matted widescreen presentation, the transfer here is quite nice overall, looking especially crisp and clear (to say nothing of creepy) throughout. The accompanying English monaural soundtrack delivers admirably, lending all the more credit to this, what would ultimately be Cameron Mitchell’s swan song to serious acting. While there are no special features present on this bare bones release, Face of Fire still comes with a hearty recommendation.