Written by Todd Ford

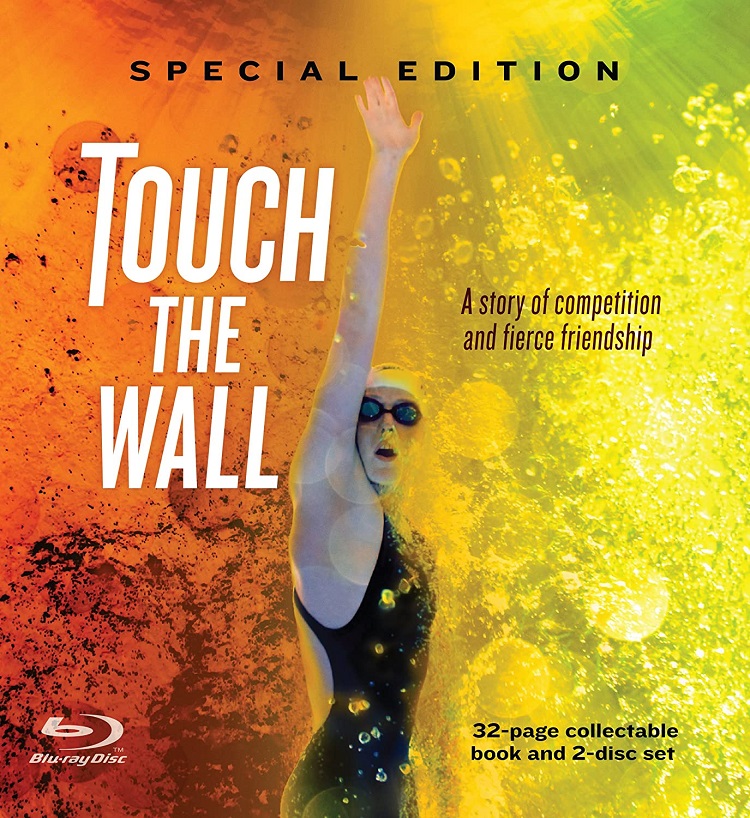

Near the end of Touch the Wall, an engaging new sports documentary—and a rare one about swimming—Olympian Missy Franklin sits and reflects on the meaning of her collection of four gold and one bronze medals from the 2012 London Olympic Games. The magnitude of what she’s accomplished is only slowly sinking in and she makes a point of giving special attention to the bronze medal. It was her first, her favorite, and yet few people ask to see it.

The scene has a way of capturing the entire movie—and the entire sport. During the heat of an Olympic year, the media and the public become so fixated on the Ryan Lochtes, Natalie Coughlins, and Missy Franklins that they forget that these tips of the iceberg stand in for the vast number of athletes who are the mountain of ice beneath the waves.

To be one of the few who make it to the top is an enormous honor and accomplishment made possible by having a body built for swimming; an almost super-human threshold for pain and pushing the limit; and luck that you have parents who can afford constant travel and pricey fast skins, that you have access to a passionate coach, and that you can make it through more than a decade of intense training and competition without suffering injury. Franklin has these in her favor and the movie knowingly illustrates them all.

The movie tells two parallel stories, actually. It’s about the sure to become life-long, sister-like relationship between Franklin and her older, already two-time Olympian training partner Kara Lynn Joyce. Attempting the difficult project of returning to the Olympics for a third time at age 26, Joyce’s story provides the drama that, frankly, wouldn’t have been in the movie with Franklin alone. At one point, Joyce sizes up her training partner, with a touch of envy. “She’s 16, six foot tall, and broad shoulders. She’s built like a swimmer.”

Swimming is a sport where a race can be 100 meters, 400 meters, or longer and yet the champions and the sixth place finishers are sorted out in the final 15 meters. If you’re swimming hard enough, it’s going to hurt—Franklin’s high school coach informs his worried athletes as they prepare for the Colorado state meet—and nothing hurts more than the final 15 meters. Swimmers talk of it as breaking through a wall to get to the wall. My swimmer daughter would say, “I don’t know how I do it. The more it hurts, the faster I can go.” Most swimmers show the pain by “dying.” Franklin proclaims, “I love to push my body to its absolute limit.”

Franklin had the great fortune of supportive parents and being an only child. They’re aware that she’s only a kid—and Franklin endearingly behaves like the kid she still is throughout much of the movie—and they’re hesitant to spend too much because there’s no way to know where it will all lead. And, yet, they keep on helping their daughter follow her dream. When she qualifies to swim in an international meet in China, her dad wonders if it’s worth the $13,000 to see his daughter swim for two minutes. I had the same dilemma on a smaller scale when my daughter qualified in one event at a championship meet in Oklahoma City (we live in North Dakota), thousands of dollars to watch one and a half minutes of swimming. My wife and I made that trip and so did Franklin’s dad.

Franklin also had the immeasurable good fortune of having a great coach in Todd Schmitz. He’s young, driven, passionate, fundamentals-oriented (he gives Joyce hope during a tough stretch by recruiting a technique coach for a day), is moved to tears as he tries to talk Joyce through an even tougher stretch (as I said, Joyce’s story provides the required drama, everything seems to come so easily for Franklin), and knows just how much to push Franklin to avoid injury. I’ll never forget the times I’ve seen swimmers—including my daughter—exit a practice early and in pain and ultimately lose months of training.

And speaking of Joyce, she provides the drama to be sure. Faced with the requirement of meeting a time benchmark to retain her $30,000-a-year USA Swimming stipend, you just know it’s going to be close. But she provides something else crucial to the story as well. She provides that element of the sport that Franklin showed while proudly holding her bronze medal. Her success story—every bit as meaningful as Franklin’s more media-sanctified triumph—is like that shiny bronze medal beside its shiny gold sisters.

My favorite moment in the movie comes as Franklin’s high school team prepares for the state meet. We see Franklin soar off the blocks. Then we see a teammate leave the blocks, almost feet first with a big splash. That’s the reality of the sport in two quick shots. Franklin is one of the very privileged very few. That other girl is like so very many others, but those so very many others strive for and sometimes achieve their own “gold medals” by qualifying for state or even having the courage to get up on the blocks at all.

I may be the best critic or the worst critic to review this movie. I have a dozen years experience as a swim parent and know, and find exhilarating, everything that’s up on the screen. My daughter went through enough drama in the sport for a movie of her own with thrills of age-group state titles, agonies of high school plateau, and pain from a knee injury. I’m acquainted with Dagny Knutson who was once considered Franklin’s rival and had just as many spectacular high school state meet swims before suffering her own set-backs. Just how much my prior knowledge and love of the sport positively affected my engagement in the movie is too close to home to call.

I can guarantee uninitiated viewers will come away with at least one impression though. Swimming is a sport filled with great people and has been the source of many life-long friendships. Looking back, my daughter’s favorite accomplishment in the sport was making friends with swimmers from every town in the state. Watching Franklin and Joyce laugh and nearly cry together while getting matching tattoos is a perfect expression of the types of friendship the sport fosters. Of course, close followers of the sport already know this.