As someone who grew up and lived far too long in a small community, I learned that drama is often looming around every street corner in such an environment. Everyone tends to stick their noses into the private lives of others, people can have often-unfair labels assigned to them at the drop of a hat, and the absence of available women – or the promiscuity of taken ones – can literally drive some men to drink. Heck, I can proudly say that I have sadly been on the receiving end of all of those maddening elements at one point in my life or another. I can also say that when something big happens to a small town, it can change the very boring and ridiculous course of damn near everything in the process.

Such is the case in Richard Fleischer’s 1955 CinemaScope feature, Violent Saturday – a unique combination of film noir and Technicolor melodrama (as adapted from William L. Heath’s novel of the same name) that somehow managed to offend some critics upon its initial release over the amount of violence depicted in the film. Perhaps those critics suffered from dyslexia, reading the title as Silent Voter Day. Or maybe they got so caught up in Fleischer’s well-executed fashion of filming the sorted, sordid lives of several families and individuals in a small Arizona town that, by the time the volcanic drama of the movie finally erupts at the finale, they had forgotten what the movie was called.

The primary plight of the pursuit of happiness here would have to be the story of top-billed Victor Mature, who plays a successful businessman whose son is ashamed his father did not serve in World War II. Meanwhile, his friend and manager – as played by Richard Egan (which was the name of the local tax collector in the town I grew up in, strangely enough) – is drinking heavily on account of his unfaithful wife (Margaret Hayes), and begins to woo a dazzlingly sexy nurse (Virginia Leith, who was just four years away from losing her head – or should I say body – in The Brain that Wouldn’t Die). Said nurse is also the apple of the eye of a peeping-tom Tommy Noonan, local bank manager.

Likewise, the bank manager is in the eye of a recently arrived trio of bank robbers, played to the hilt by leader Stephen McNally; the brainy J. Carrol Naish (in one of his rare non-ethnic roles), who is one of the nicest bad men you’re likely to meet on film; and the brutish Lee Marvin, who has no problem with knocking small children upside the head or killing Amish folk. And speaking of the Amish, the already-rising talents of a young Ernest Borgnine are also involved in this Violent Saturday as the patriarch of an Amish family who become part of the thieves’ big eponymous scheme – wherein everyone else mentioned thus far is called upon to sink or swim when all the cards are down and all the bets are off.

Rotten mixed metaphors aside, Violent Saturday is a fascinating look at life in a small town that builds up to a big payoff – one that Fleischer and company handle most efficiently. Even the smallest of supporting roles – such as the crime drama veteran Sylvia Sidney in a bit part as a librarian in trouble with the bank – seem to get just enough screentime for whatever well-trained character actor is inhabiting them to develop them properly. Likewise, Mature gets a chance to strut his stuff as a man of action in this pulp noir film’s finale, which undoubtedly served to inspire Peter Weir’s equally-good Witness (and if you’re a fan of Witness you owe it to yourself to see Violent Saturday).

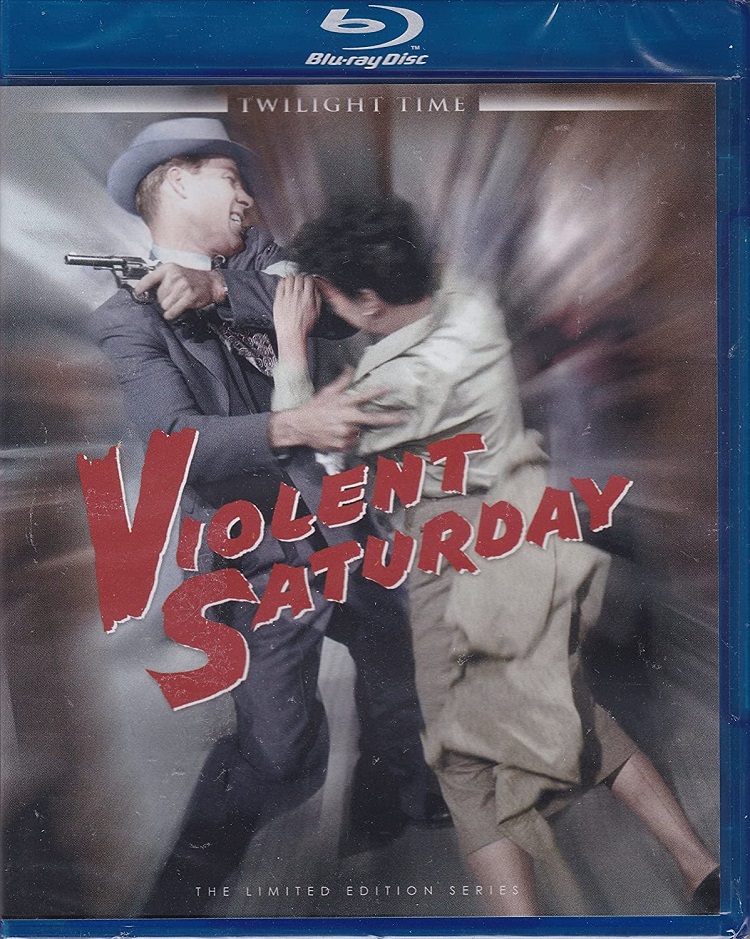

More than three years ago, Twilight Time issued Violent Saturday as their second DVD release in a non-anamorphic presentation (which is how 20th Century Fox issued the elements to them). This new Blu-ray version is a dynamic improvement over the old disc, presenting the movie in its proper aspect ratio and with a very crisp and clear transfer overall. Truly, it’s a beaut, folks. A DTS-HD MA lossless 5.1 audio mix accompanies the film, as does a secondary audio DTS-HD MA 2.0 track containing composer Hugo Friedhofer’s isolated score. A third audio option consists of a new audio commentary by Twilight Time’s resident film historians Nick Redman and Julie Kirgo, the latter of whom also provides us with some extensive liner notes.