Written by S. Edward Sousa

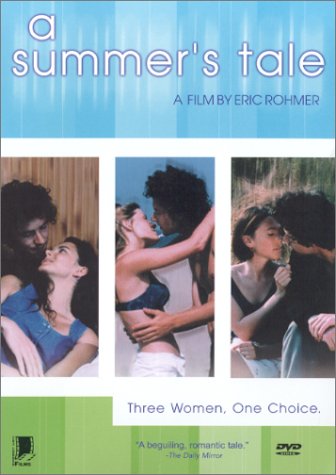

French filmmaker Eric Rohmer was in his mid-seventies when in 1996 he wrote and directed A Summer’s Tale, the third in a quartet of features grouped together as Tales of the Four Seasons. It would take another sixteen years for the film to find distribution in America. Dissecting love and sex with philosophical precision, A Summer’s Tale—like most of Rohmer’s films—avoids ideologies, opting to unpack the contemplative emotions of man infatuated. It’s a marvel that Rohmer, at his age, captured the uncertain and self-serious nature of being on the cusp of adulthood. Over the days of summer, Rohmer breaths a sympathetic earnestness into the quixotic and directionless young man, Gaspard, who, through all of his soulful consideration, is never ostentatious. It’s a testament to Rohmer’s ability to recognize characters as an idea outside himself, for Gaspard is without the clarity or wisdom of reflective and sentimental old man.

In point of fact Gaspard, a pensive college graduate sojourning to the beaches of Bretagne, France for summer holiday in search of a distant girlfriend, is eager to find a bit of this aged world weariness. He arrives with little more in tow than a guitar and a sack of clothes, strumming six-strings and rambling philosophical for a series of girls he hopes will inspire him. The first is Margot, a waitress who spends the film playfully teasing Gaspard while indulging his romantic musings. An ethnology student, Margot brings Gaspard along to meet an old merchant sailor and record shanty songs. Inspired, Gaspard appropriates the mariner’s point of view and writes his own shanty, the tale of a woman pirate whose heart belongs to the sea. He spends the rest of the film trying to fit various women into the lead role of his siren’s song.

Next is Solene, a by her own admission “principled” young women who’s in touch with herself. Her boyfriend is off on holiday, and after meeting at a nightclub, Gaspard gets the notion she’s his for the taking. The attraction is mutual, but Solene demands a bit more out of our whimsical man-boy; finding his romantic nature weak-willed, she refuses to be a source of poetic musing.

Then Lena arrives, the missing girlfriend who’s been incommunicable in Spain and is both happy and frustrated to find Gaspard waiting. Their interaction is tense as they make sense of the limitations of their love. They’re at a critical juncture; entering into the age of responsibility commitment seems inevitable, making every choice so critical, so weighted. In response these characters engage in emotional conflict, but none desire any long-term turmoil.

Except perhaps for Gaspard, who wants to be wanted by women more than he wants an actual woman. He meanders through the summer feverishly seeking feminine attention, only to be disappointed as soon he receives it. When one of the Summer Betties tells him, “You’re just an ordinary tourist,” Gaspard responds, “I can live with that.” He moves between the girls and their emotions in attempt to satisfy his own, agreeing in frustration to commitments then staggering away brokenhearted when they collapse.

Rohmer generates empathy for Gaspard, played by Melvil Poupaud, through a series of reflective days rather than through a series young man’s sex-crazed exploits. Passion runs high, but they foment in weighty and idealistic shoreline conversations. The action and the plot feel secondary to the personal evolution of Gaspard and the women. Unlike most American filmmakers—Kelly Reichardt and Richard Linklater being two of the few—Rohmer stews on the unspoken, creating characters whose minds seem to exist beyond reel boundaries. Perhaps this is why the film took so long to get across the Atlantic; American movie goers require finality, even when they expect a sequel, leaving cinematic musings to capture critical praise but drown at the box office.

A Summer’s Tale, a subtle, joyful film opening July 18th in Los Angeles, never takes itself too serious. It captures the wandering spirit of aimless young adults without any of the annoying self-obsession or imposed finality. Rohmer seizes the moment by avoiding hindsight observations, allowing people to find their way for themselves.