Five seems to be a lucky number for author Mark Harris. His previous book, Pictures at a Revolution, artfully captured a key inflection point in movie and American history by examining the five Best Picture nominees from 1967 (a group that included Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?, The Graduate, Bonnie and Clyde and the eventual winner, In the Heat of the Night, as well as the joker in the pack, the dreadful Rex Harrison musical version of Dr. Dolittle).

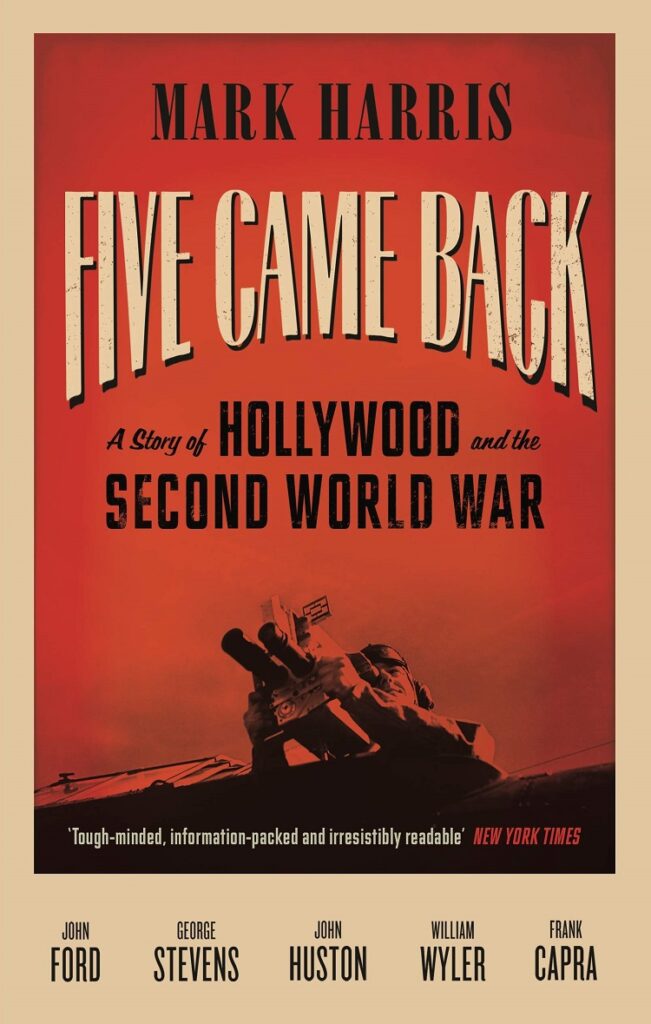

Now he has successfully tackled a tough genre, the group biography, with Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War. In entertaining and informative detail, the book looks at the wartime service of five major Hollywood directors (John Ford, George Stevens, John Huston, William Wyler and Frank Capra), charting not only how they affected the war but also how the war affected them, both personally and professionally.

This is a fascinating and extremely well-researched book, relying on extensive access to original source material including letters, cables, and internal movie studio and government memos. It wears its scholarship lightly, though; Harris, a long-time entertainment writer/commentator, has a good grasp of the telling quote that provides insight and perspective. Some of the letters written home to wives and children are particularly touching, as the directors’ months of service and travel to Europe, Africa, and Asia stretched into years.

It’s a great subject, interesting both for the differences and the similarities to today’s politics and movie industry that are revealed in the stories of these five very different men. One common theme is their willingness to throw themselves into the war effort, at what could have been (and in some cases was) considerable cost to their professional careers.

Those careers were already well under way for four of the five: Ford, Stevens, and Capra had all started out in silent films and each made important films in Hollywood’s golden year of 1939: Ford’s Stagecoach, Stevens’ Gunga Din, and Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Wyler’s career was just hitting its stride – his most recent films included The Letter and The Little Foxes, along with a happy accident of timing, the aren’t-the-English-people-swell melodrama Mrs. Miniver.

In some ways John Huston had the most to lose from a years-long career interruption: a semi-successful screenwriter, his Hollywood stock had shot up with his 1941 directorial debut, a minor little classic called The Maltese Falcon. Yet for reasons both simple and complicated, these middle-aged husbands and fathers (Ford, born in 1894, was the oldest; Huston, the youngest, debuted in 1906) put themselves in the service of their country, seeking adventure, commitment, and the chance to do something real beyond the dream factory that Hollywood was and in many ways still is.

What’s strikingly similar to today is how history repeats itself, particularly in the ways movies portray America’s enemies. For example, Japanese characters, either invisible or caricatured as silly houseboys and dragon ladies, morphed almost overnight into horrifying racial stereotypes. Filmmakers and presumably audiences, understandably panicked by Pearl Harbor, were being told it would be necessary to wipe out the Japanese as a race in order to win the war.

Ironically, in some cases it was government officials rather than the artists and studio execs who were voices of sanity, reminding the filmmakers that racial hatred was the stock in trade of their other enemy, Hitler. Harris doesn’t draw a parallel to the way Muslims and Arabs were/are stereotyped and profiled after 9/11, but he doesn’t have to.

The historical perspective he does bring is also helpful in identifying how the directors aggrandized their own heroism, and their films’ fidelity to battlefield realism, both from day one and in following years. Not that they didn’t demonstrate real physical bravery: Wyler flew with bombing missions over Europe to gather footage that would eventually become the documentary The Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress, and Ford was injured directing what would become The Battle of Midway. Huston had a shattering psychological experience near the front lines in Italy that made him anxious to make Let There Be Light (original title: The Returning Psychoneurotic), a long-suppressed documentary about returning veterans dealing with what we would now call PTSD.

Harris is also quite good at discussing the impact on each man’s post-war work. George Stevens, who filmed the liberation of the Dachau death camps (just the descriptions are harrowing), had made light, sophisticated comedies before the war, including the delightful wartime-in-Washington romance The More the Merrier, with Jean Arthur, Charles Coburn, and the often underrated leading man Joel McCrea. After the war he never made a comedy again, despite the urging of his friend Katharine Hepburn. Wyler, who lost much of his hearing during the war, channeled his alienating experiences as a returning veteran into the still-relevant, still-stunning The Best Years of Our Lives.

Capra, who tried hard to serve by supervising the Why We Fight series, in some ways comes off the saddest of the group. His confused, naïve politics, which are evident in his films (The people are a cheering crowd! The people are a screaming mob!) left him foundering in a subtler, more complex post-war world. The initial failure of his first post-war feature, It’s a Wonderful Life, shook his confidence. (Today, after repeated viewings, Capra’s filmmaking skill and grasp of simple emotions, along with Jimmy Stewart’s performance, have woven the film into our national mythos.)

There’s lots more strong stuff in Five Came Back. This book is catnip for film and history buffs, but there’s plenty there for a reader just interested in a good story, or insight into five remarkable men at a remarkable time.