New York City used to be a dangerous place. No, really. This will not be news to anyone who lived in or near the Big Apple in the 1970s, but for those who have only seen the sanitized, Disneyfied Times Square of today, it might be hard to believe.

Of course, there are still parts of New York that are less than savory, if not downright menacing. But they look like high-security gated communities with manicured lawns compared to the nightmarish, decaying city depicted in the 1979 film Boardwalk, now available on DVD. With its graffiti-emblazoned subway cars and violent street gang of black and Hispanic youths, it’s the frightening city groused about by Archie Bunker and patrolled by the well-meaning but hamstrung cops led by Barney Miller.

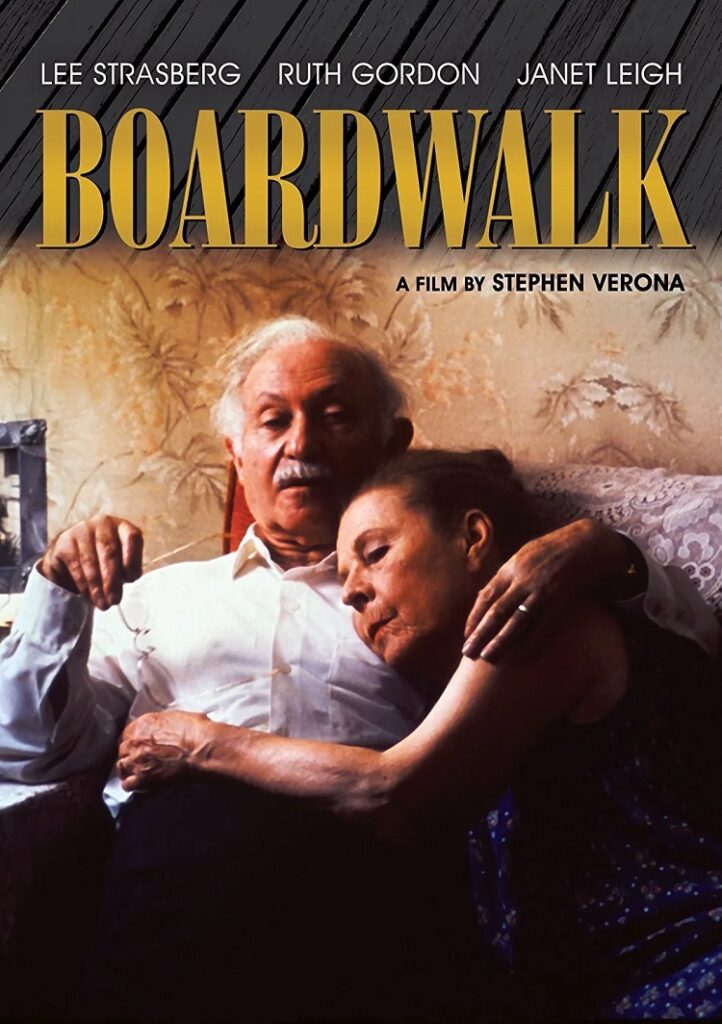

The film itself is an odd little mish-mash, not without its charms, that uneasily combines multi-generational family tensions, white flight, terminal illness, old Jews menaced by the aforementioned street gang, and a truly touching love story enacted by two octogenarian pros: legendary acting teacher Lee Strasberg and indomitable eccentric Ruth Gordon.

Strasberg and Gordon play David and Becky Rosen, married 49 years and living in Brighton Beach, close to the Coney Island boardwalk that gives the film its title. He’s wise, kind but tough; she’s a Jewish mother but not the smothering, castrating, Philip Roth kind. They both still have their wits about them and are, at the start of the movie, both in relatively good health, and even still have a sex life. If you’ve ever had the kinky desire to see a film with Lee Strasberg and Ruth Gordon in bed reading a Playboy magazine together, I would bet that Boardwalk would be your one and only opportunity to fulfill it. (I know, I know. Some of your grandparents still have sex. Get over it.)

Legendary motel occupant Janet Leigh plays one of David and Becky’s three grown children (it must have been some spin of the genetic wheel for two shtetl Jews to produce a Hitchcock blonde). She’s a high-strung middle-aged woman who settles for a schlubby second husband (Merwin Goldsmith). Her mid-20s son, played by David Ayr and sporting a Greg Brady Jewfro, is a soft-rock musician who gets involved with a pretty blonde (Forbesy Russell), but the story loses track of her about two-thirds of the way through. Boardwalk has nothing if not lots and lots of subplots.

The film’s through-line involves the gang, led by Kim Delgado as Strut, and their escalating crime spree (petty theft at the cafeteria David and his family run, as well as home break-ins, muggings, assaults, and synagogue desecration). David stoically accepts these attacks and other tragedies, all markers of the decline of the neighborhood, the city and perhaps the whole country, but in the end he and Strut have a final, fatal confrontation. Spoiler alert: that wimp Charles Bronson needed a gun to stop the bad guys in 1974’s Death Wish; actual tough guy Lee Strasberg, white-haired and bespectacled, uses his bare hands.

I’m making jokes because Boardwalk is all over the place in terms of storytelling, tone, accents, and acting style, with a meandering pace and lots of local color. In other words, it’s a 1970s movie, but co-writer/director Stephen Verona is no Robert Altman, Francis Ford Coppola, or Martin Scorsese. Maybe he hoped to be Scorsese; his other major directing credit is The Lords of Flatbush (1974), an ensemble piece about black leather jacket-clad street toughs that featured Henry Winkler, Sylvester Stallone and Richard Gere just as they were getting ready to hit it big.

Gordon and Strasberg embody most of the reasons to see the movie, less for what they do here than for who they are and the associations they bring. He’s quite good in this film and also in another 1979 release, Going in Style, in which he co-starred with George Burns and Art Carney playing three Golden Boys who decide to rob a bank. Strasberg holds his own with the two shameless comedic scene-stealers and also has a lovely, touching moment when he remembers spanking his son for a long-ago, long-forgotten infraction, with the son stubbornly refusing to admit his guilt, then finally breaking. I still remember Strasberg saying, with infinite sadness in his voice, “We never had any fun after that.”

I’ve been in love with Ruth Gordon since I first saw Harold and Maude, and my love deepened when I read her autobiography My Side and several other of her chatty, Gordon-centric memoirs. She was a true trouper who carried the history of the American theater in the 20th century with her; she made her stage debut in 1915 in Peter Pan and when she won the Best Supporting Actress Oscar for 1968’s Rosemary’s Baby, her acceptance speech began “I can’t tell you how encouraging a thing like this is.”

By the way, I’m convinced Gordon, playing Minnie Castevet, won the Oscar because of one tiny gesture. Remember near the end of the movie, when Mia Farrow’s Rosemary is trying to rescue her child from the coven of modern-day witches that has stolen it? She comes into the Castevets’ apartment armed with a long kitchen knife. However, when Mia gets her first glimpse of her demonic offspring, she drops the knife in shocked horror and it sticks into the floor. Ruth Gordon pulls the knife out and hastily smoothes away the messy gouge that the knife’s point has made. Minnie may be a Satan-worshiping witch who has conspired to pimp out Rosemary to the devil and bring about the birth of the anti-Christ, but she’s a house-proud bourgeois first: you do not mess up the hardwood floors of her rent-controlled pre-war apartment!

See Boardwalk to watch a couple of pros do their thing with skimpy, melodramatic material, or as a time capsule from the seedy, scary New York that was, but be aware that the movie itself is no day at the beach.