Directed by Fritz Lang, who co-wrote the screenplay with Thea von Harbou’s, M (1931) stars Peter Lorre as Hans Beckert, a serial killer of children on the loose in Post WWI Germany. The film isn’t a mystery because early on we learn Beckert’s identity. Instead, it is a thriller steeped in social commentary that is just as relevant today.

The murders become a form of mass entertainment. Mob mentality causes many people to be unjustly suspected and attacked due to gossip and rumors. The local crime leaders get involved with the search for Beckert because the increased police activity is disrupting their businesses. When they corner him in an office building, they knock out the guards and tear up the building trying to find him. The criminals put Beckert on trial where he argues that he can’t control what he does while the others make a choice to do wrong, so who are they to judge him.

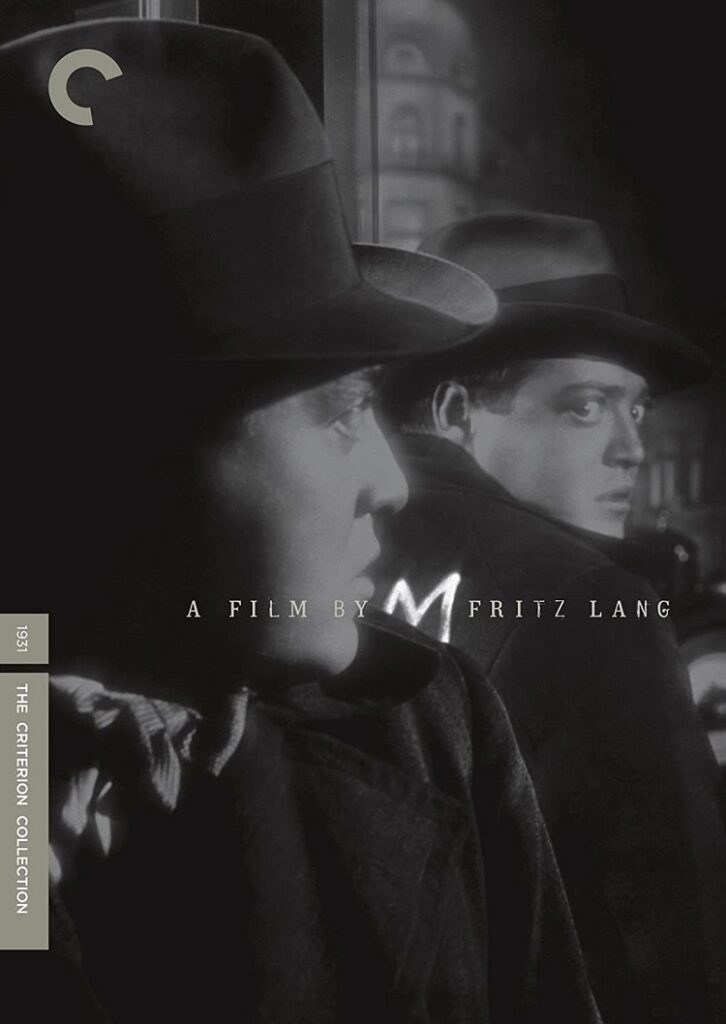

M is a feast for the eyes. Lang was part of the German Expressionism movement, which started in the silent era. This film is a fine example of how good black & white can look, especially it its use of shadows. As a director, Lang makes a number of great decisions that elevate the film. He never shows you the murders, leaving it all to your imagination. He has parallel scenes running where both city officials and gang leaders are holding meeting about what to do about the serial killer. The scenes are intercut so a city official will start a sentence with a criminal finishing it and vice versa. He places the camera in interesting positions and has a great tracking shot that runs through the beggars’ den.

There is audio commentary by German film scholars Anton Kaes, a teacher at UC Berkley and author of BFI Film Classics volume on M, and Eric Rentschler, a Harvard professor and author of The Ministry of Illusion: Nazi Cinema and Its Afterlife, who discuss the merits of M as a film and a historical document. They reveal that Beckert was loosely based on a real killer in Dusseldorf in ’29, so the film was very topical in Germany. The effect of WWI is apparent throughout the film, but no mention of it is made. We see many unemployed and crippled beggars, remnants of the war, which became so obvious when they are pointed out.

On the supplement disc, Criterion rises to the top again with some amazing finds. Conversation with Fritz Lang is a 50-minute conversation between directors Lang and William Friedkin shot on February 21 & 24, 1975, a year before Lang died. He talks about growing up in early 20th century Europe. M is anti-death penalty, but Joseph Goebbels, Nazi Germany’s Propaganda Leader, and the right wing press mistook it for being pro. Lang fled Germany after being offered the job of the leader of German film and to make the National Socialist film.

More can be learned from Lang in the ’63 interview that appears in the liner notes. French New Wave director Claude Chabrol made a 10-minute version of M for the French television program Cine-Parade that aired in 1982. It covered the basic motifs down to shot selections. Chabrol appears in a short interview segment discussing Lang’s films and techniques.

There are classroom audiotapes from the New School University with M editor Paul Falkenberg discussing the film and its history in 1976 & 1977. While an unbelievably impressive find, he didn’t provide much insight that was worth learning other than the bit of trivia that Lorre doesn’t do the whistling. Lang’s wife did. This can be skipped.

A Physical History of M is the best item of the bonus materials as it shows the different ways M has appeared over the years. When it was re-released in theatres, a new credit sequence was created and audio was added to the intentionally silent sequences. This documentary shows a comparison. It also shows how Lorre’s finals scenes in M were used in the anti-Semite propaganda film The Eternal Jew (1940). This documentary also shows how M was altered and in some instances butchered in France. When Beckert first appears as a shadow on the wanted poster, the scene was reshot so the poster would be in French. During the film’s climax, when Beckert talks about his crimes in front of the criminals’ kangaroo court, Lorre reshot his scenes speaking his lines in French. Those scenes were inserted into the film with the original footage that was dubbed. The biggest travesty is that meaning of the picture was changed by the alteration of the final scene. Lang showed grieving mothers in court, issuing a warning to themselves and the audience. This was changed to a scene of children playing carefree as if to say that now the trouble is over. Whoever made this decision missed the entire point of the film. The film was no longer a warning for parents to better protect their children, but became a simple thriller where murder was part of the entertainment, which was something Lang was against.

Criterion’s two-disc set of M is a must-have for any serious film library.