Nothing is obscure anymore – or nothing can remain obscure. Internet information proliferation flattens structures. Getting information on John Fahey is just as easy as getting information on John Lennon, or Elton John, or thousands of other musicians who sold orders of magnitude more records. Wikipedia has an extensive article on all of them, with no secret handshakes or special backrooms to go to. Obscure isn’t obscure anymore, or at least it cannot remain so for long.

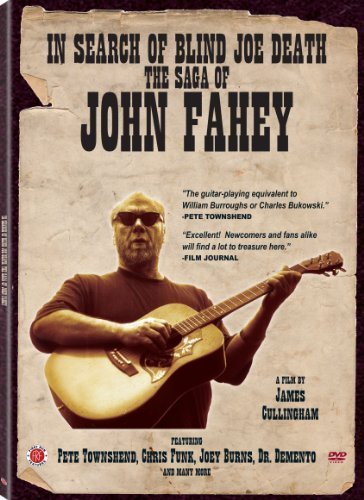

That this is a recent thing in culture is one of the points brought home by the excellent new documentary In Search of Blind Joe Death: The Saga of John Fahey. A mercurial and strange man who played mercurial and strange music, sometimes folky and recognizable, sometimes anything but. When he began recording music, he had to form his own label way back before doing so was cool.

He was odd, often original, but he took his techniques from the legitimately obscure and hard-to-find sources that came before him. In Search of Blind Joe Death, which serves as a general biography, both personal and musical, details the hard research and in-depth analysis that John Fahey made of the folk and blues traditions he played in and, later, expanded. Barry Hansen (who, when he puts on a hat, becomes Dr. Demento) tells of how he and Fahey, both working in the UCLA folk-music masters program, would travel through the south in black neighborhoods, going door to door and buying up old phonographs for a quarter a piece. At the end of his life, Fahey was making ends meet doing the same thing – trolling record shops in Oregon, finding the rarities and selling them to collectors.

This brief (57 minutes) documentary is uncommonly well balanced. There is a tendency for docs on small beloved subjects to over-superlative. If a filmmaker has enough interest in something to go to the trouble (and limited hope for reward) of making a documentary about it, the subject is usually personally important. This personal importance can get in the way of objectivity, and cause overstatement or hagiography. John Fahey is not presented as the most influential guitarist of a generation, for surely he was not, nor as the greatest guy or under-recognized genius. He was a fine guitarist in a specific idiom, who experimented with varying levels of success, and a strange and amusing character. Refreshingly, for this film, that is enough, and there is no need to put the weight of “super-undiscovered genius” on Fahey’s shoulders.

The style of the documentary is familiar – old interviews and television appearances of Fahey, newly shot talking-head interviews with real-life friends and admiring musicians (including Pete Townshend, whose entire 30-minute interview is included as a bonus feature on the DVD.) What little narration the film uses is always Fahey’s words read by the director. There is little editorial or directorial interjection. Even in latter days, when his recordings were basically electric guitar noise and shouting, the film slyly places a bit of a interview with Fahey where he admits this music he’d ‘discovered’ already existed, and was called “Gothic Ambient Industrial” (and is no less annoying in the hands of an old master than it is in the young angry people who did it before him.) Then the film plays a little of it, letting the audience make up their own minds as to how terrible it really is.

In Search of Joe Blind Death is an admirable success. It stays out of its own way, never getting overly cute – there are brief animations and several shots of turtles, for which Fahey held a particular fondness. The subject remains the subject, and it contextualizes and recontextualizes the phases of Fahey’s life – obsessed record collector, outre acoustic guitarist, aging statesman living in semi-squalor. It brings the man into view in a way no Wikipedia discography and crowd-sourced article could manage, and somehow does not diminish his mystery. John Fahey, heavy-lidded eyes and Muppet-like voice, stays weird (and weirdly fascinating) throughout.