Ulrich Seidl’s Paradise: Faith is the second film in the Austrian director’s Paradise trilogy. It comes on the heels of Paradise: Love and precedes Paradise: Hope. Seidl’s series explores the stories of three women as they search for purpose and a sense of belonging in the world.

Where the journey of Paradise: Love took its Teresa (Margarethe Tiesel) to Kenya for sex tourism, Paradise: Faith takes its lead character on a journey inward. The picture explores the impact of the protagonist’s religious life and how faith can prove a dominant and distinctively gratifying entity.

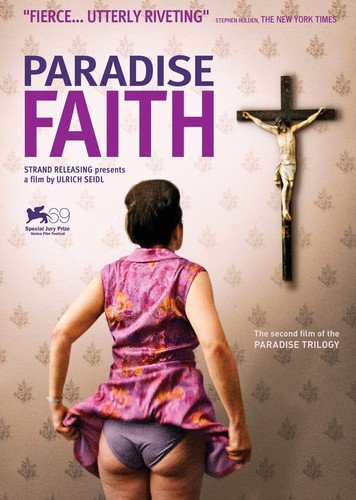

Maria Hofstätter is Anna Maria, a woman in her 50s who just so happens to be the sister of Teresa. She works as a nurse and is a devout Catholic. When she takes a vacation, she uses it to serve as a local missionary. Anna Maria also spends time atoning for her sins, which includes rites of self-flagellation in front of a crucifix.

Anna Maria’s religiously regimented world is thrown into a tailspin when her husband Nabil (Nabil Saleh), a devout Muslim, returns home after two years away. Nabil is a paraplegic because of an accident and wants his life to return to normal, but he struggles with his wife’s newfound religiosity. She blames his iniquity for his condition and now sees it as a gift from above.

Paradise: Faith is a bleak film of sorts, but it’s also deeply authentic in its expressions of religion. Scenes of Anna Maria wandering door-to-door through apartment complexes and offering a statue of the Virgin Mary ring authentic. This behaviour gets her into some sticky situations – and even a dangerous one – but her faith is unwavering.

Doubtlessly, Anna Maria’s Catholicism serves as the “other man” she’s moved on to after Nabil’s mishap and exodus. Her conviction fills the emptiness and her Christ takes the place of her husband. Her needs are met through the cross and Seidl’s examination of this is not a form of ridicule. He instead seems sympathetic.

That puts Nabil at a disadvantage when he returns, as his place has been taken. He no longer plays a role in his wife’s life, which causes him initial confusion. But as he rebels against her faithfulness, the relationship between husband and wife intensifies in ferocity and negativity.

Nabil’s understandable frustration at his wife’s new love eventually proves volatile, as he wheels around the home knocking Christ paraphernalia off walls. This humorous outcropping becomes violent when he suspects Anna Maria of cheating and it further increases as Paradise: Faith progresses.

Through it all, Anna Maria clings to the cross. God is testing her, she believes. When Nabil comes upon a prayer group and abusively responds, Anna Maria and her fellow Christians treat the situation as though a demon has arrived. Later, she splashes holy water on her hubby as he sleeps.

Paradise: Faith finds yet another woman in search of joy where humanity is fragile. If Seidl’s trilogy feels austere, it’s because its characters are defined by their urges. Anna Maria sees her missionary work less as helping human beings (note how she indistinctly treats the comical Mr. Rupnik) and more as doing the immediate will of Christ.

That she views her life with Christ as another marriage, complete with ritualized sexual longing, underscores this aspect. For her, life is a trial and her muscular compensation dangles on the cross that sits above her bed. And when Anna Maria tucks in and glides the hung Lord under the covers, it’s a little taste of paradise indeed.