The 1960s were a time of enormous cultural upheaval. The aftermath of World War II found many countries with a bountiful economic boom. All that industry and workforce developed to win the war moved away from making bullets and onto inventing all sorts of gadgets designed to make life easier for a quickly developing middle class. All those babies booming were growing up so that by the 1960s those kids were teenagers who knew life not of the Great Depression or of war but of a seemingly unending prosperity. Their values began to change along with this new lifestyle. Social norms began to break down. Sex and drugs began to become mainstream. Racial equality and women’s rights were being fought for in the streets as well as the ballot boxes. The never satiated consumerism of their parents’ generation was being sneered at with words like “Free Love” and “Peace” replacing them like mantras.

Popular culture began to reflect these new norms as well. Rock and roll celebrated this more liberated lifestyle, beat poetry was read in the streets, and the movies became less censored. None of this happened overnight and the cinema arguably changed slower than the rest. Take for example Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom. Made in 1960, it revolves around a murderer who attaches a blade to his camera so that he can records his victims facial expressions as he murders them. It was so controversial upon release that it essentially ruined the famed director’s career. Six years later, Michaelangelo Antonioni made Blowup which also involves murder, sex, and photography and it became a critical darling.

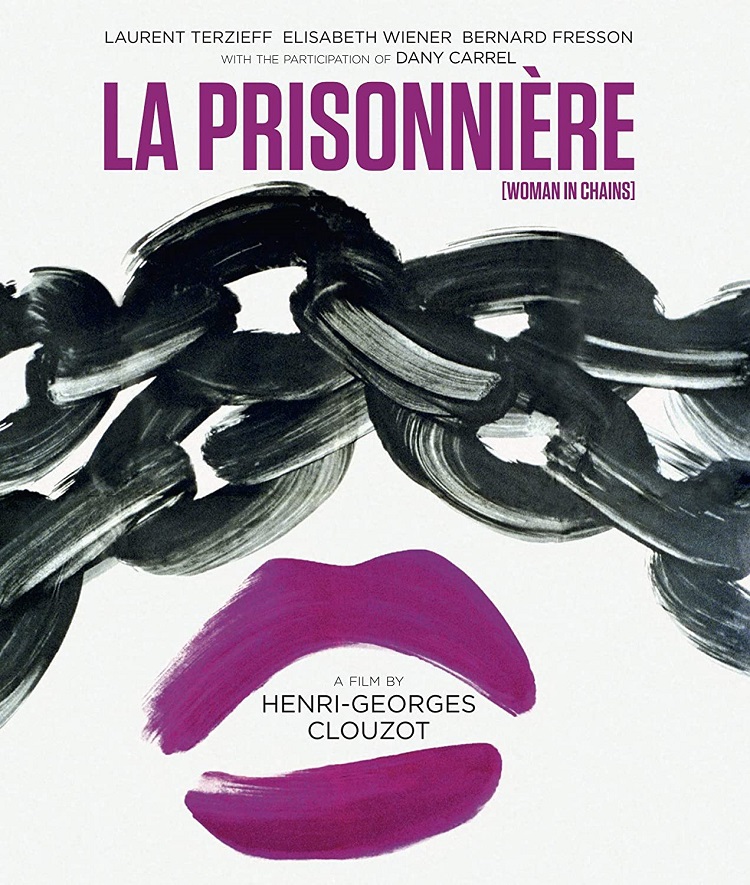

In 1966, acclaimed director of such classics The Wages of Fear and Diabolique, Henri-Georges Clouzot directed La Prisonnière (sometimes called Woman in Chains) yet another film involving sex, violence, and photography. It was the last film he made before his death in 1977 and the only one he shot in color. Considering the sumptuousness of the cinematography (by Andréas Winding) and the fascinating path the story takes, one so very different than his other films, it is a real shame he ended his career on it.

Set within the modern art world of Paris, La Prisonnière involves three characters – Gilbert (Bernard Fresson), an avant-garde artist; his wife José (Élisabeth Wiener); and art-gallery owner Stanislas (Laurent Terzieff). Gilbert and José consider themselves very modern and have an open marriage. But when José finds Gilbert openly flirting with a critic with whom he hopes to receive favorable notices, she becomes jealous. Annoyed by her own conservative feelings, she goes home with Stan. At his very hip apartment filled with lavish artwork, she asks him to show off his own photography. They are mostly austere shots of other people’s handwriting but there is one shot of a nude woman, kneeling on the ground, bound by chains. He acts as if that was accidentally included in the set but she is both embarrassed and intrigued. When he tells her that he pays women to pose for him like that, she decides to sit in on one of this photography sessions.

In a brilliant scene, José watches this young model enter the room and do exactly as she is told. She dances, she takes off her clothes, and puts on a clear plastic top. Stan takes photos of her and barks orders. José is both turned on and appalled. Eventually, she runs out. She couldn’t take anymore. But the next day she visits Stan and asks to come to another session. He makes her call the model and apologize. Then he tells her to pretend the woman is there with them and has her bark the orders. Slowly, Stan brings José into his world of sex and submission. She thought she was so free, but he shows her not only was she caged by society’s expectations but that she likes the cage. She enjoys being submissive. Yet he is his own prisoner. His entire life he has kept himself devoid of emotion, walled off from passion and love. When he begins to feel something for José, he doesn’t know what to do. Gilbert too is trapped. He was once in advertising but left for the freedom of being a full-time artist, yet his art is being mass produced in order for him to make money. He thought his relationship with José was free from normal society, yet he becomes insanely jealous of her time with Stan.

Clouzot in his own way is freeing himself. The loosening of cultural norms and cinematic censorship enabled him to make a film about sexual obsession, filled with eroticism and nudity that he could never have made only a few years prior. It reminds me of Alfred Hitchock’s Frenzy in that way – a master of the classic suspense film finally allowed to be free with his own obsessions without constraint. Like Frenzy, this new found freedom doesn’t work as well as his previous films. Neither Hitchock nor Clouzot were quite prepared for modern filmmaking. Both lost their mass appeal in the 1960s, but were then later beloved as true auteurs. Unlike Frenzy or anything Hitchock or Clouzot ever made before, La Prisonnière is a kaleidoscope of color and visual design. He uses the abstract, tactile artwork to play with the audience’s perception, often making us view a character through a work that bends and multiplies the visuals. The end of the film includes a long, hallucinogenic scene that is a visual feast.

Most of that last act is where things become more normal and less interesting. Stan and José runaway to a seaside resort for a perfectly normal romantic getaway. Clouzot films it in extreme romantic terms. There is a moment with them standing on the beach with the wind blowing her hair and the lighting is just right where it feels like we are in another film entirely. That things eventually break down and he runs off scared when he realizes just how normal everything is doesn’t completely bring the film back to its off-kiltered, utterly interesting beginning.

Kino Lorber has given it a new 4K presentation with a 1.66:1 transfer. Extras include an audio commentary from film historian Kat Ellinger, an interview with Élisabeth Wiener and a written essay from film critic Elena Lazic.

While certainly not a perfect film, and one where the first two acts are much more interesting than its more straightforward back end, La Prisonnière is a fascinating film from one of France’s great directors. It certainly makes me wish he had been able to make more films.