The first thing to get used to in an Ozu film is the camera perspective. He never (or at least rarely) does the normal over-the-shoulder shot and counter shot for conversations. Ozu tends to shoot things from a constant upward angle. It has been analogized to a POV from someone sitting, in traditional Japanese style on a mat, legs folded underneath. The view is tilted slightly upward, never straight on or from above.

The second element of Ozu’s filmmaking that has to be taken into consideration is the secondary nature of the plot. There are stories in all of his films, but they can usually be described in a few words. Tokyo Story: An old married couple visit children who are too busy to spend time with them. Late Spring: An old man living with his daughter pressures her to marry. Flavor of Green Tea over Rice? A couple from an arranged marriage find out they might actually love each other.

From this very minor acorn, the oak of an Ozu film is grown. Released in 1952, Green Tea begins as kind of a girl’s night-out comedy. The first scene involves Taeko, the aunt of Setsuko, taking her out on the town. Taeko is dressed in a Kimono, the young Setsuko is in a Western dress. The division of generations is important to the story, and plays out in surprising ways. Setsuko is in her early 20s, and is coming into the critical age where she must be married away lest she seem peculiar. She becomes part of a girl’s weekend at a spa, with Taeko aunt and some of her school friends. To get away, Taeko has to lie to her husband about taking care of a sick friend.

While at the spa, the ladies gossip cattily about their husbands, and nobody is as bitchy as Taeko. “Mr. Bonehead” she calls him, for his slow, sluggish provincial ways. He’s from the country, and she’s a Tokyo girl. She loves to make fun of him, and Setsuko joins in, even though she’s not too comfortable with it. Days later, she comes to her aunt looking for help – her own parents have set up with a marriage arranger, and she has a date with her soon-to-be fiancé on the weekend. Surprisingly, Taeko tells her it’s her duty to go through with it. She and her husband were arranged together, and that’s just the way things work.

Meanwhile, said husband Mokichi has become friendly with Non-chan, a boy Setsuko knows who was just started work at Mokichi’s firm. They go together to a pachinko parlor, where the owner recognizes Mokichi – they are old army buddies from WWII. They get together, drink, and the parlor owner starts singing old army songs. It’s a parallel to a scene with the girls at the spa, where they sing songs from their youth between making fun of their husbands. The man never talk about their women at all.

The tension in Ozu’s movies is rarely about the plots – nobody is in a life and death struggle, there is no plot-wound time-clock where the couple has to get married before noon the next day or something terrible will happen. The tension is between competing social mores: modernity versus tradition. Urban versus rural. Tradition against individuality. And the tensions are brought out through subtle gesture of character, rather than melodrama or broad dramatic strokes. In The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice, a major conflict is Taeko’s distaste at her husband’s preference for putting soup on his rice. They don’t do that in Tokyo, and she doesn’t want it done in her house. The other plot strand is about Setsuko standing up a date with a man who has been potentially arranged to marry her. Taeko is furious – Setsuko can’t just do whatever she wants. The uncle is more blasé. He tells Setsuko to go, and when she doesn’t he doesn’t push too hard.

The best of Ozu packs an amazing emotional wallop. When talking about his films to a friend, I once described them as movies where nothing happens, and you’re in tears at the end. The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice, I think, can be considered minor Ozu. It has all of the master’s structural and formal excellence, but the story and its resolution doesn’t have the devastating effect of his greater films. That might be by design, though: Green Tea is not the slow-motion tragedy of some of his other films. It’s a mild satire on Japanese modernity, and on a basic level a romantic comedy. It just happens that the romance is not between a young star-crossed couple, but a pair of middle-aged already married people who discover, against all odds and their inclinations, that they might actually love each other.

As is typical for Ozu, the acting is understated and uniformly excellent. His taste for overt emotion and overstatement waned as he grew older. A second film of Ozu’s, What Did the Lady Forget (1937), is included in this Criterion Collection release. It’s a similar story: uncle and niece pitched against an overbearing aunt. But it is played for more broad comedy and some of the barely-there gags of Green Tea are shoved front and center in that film. It’s interesting to see, in 15 years, how much of the master’s storytelling had matured (far less is spelled out in Green Tea), but also how much of his basic technique was already intact. Domestic drama, understated, low-angled compositions, scenes that are mainly domestic in nature and approach.

The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice is a pleasant, frequently amusing film of deliberate pace. Tokyo Story and Late Spring would come to mind sooner than this film when introducing a budding cinema fan to Ozu. But it is an interesting, and entertaining demonstration of his minimalist technique. It has some of the magic of Ozu, where the very particular, very small somehow becomes universal. He is one of the most Japanese of filmmakers, but by focusing on the nuance of human relationships he speaks to the whole world. The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice is fun, often funny, but as it reaches its conclusion it touches on the universal desire for contact and understanding. A minor film, and a minor triumph.

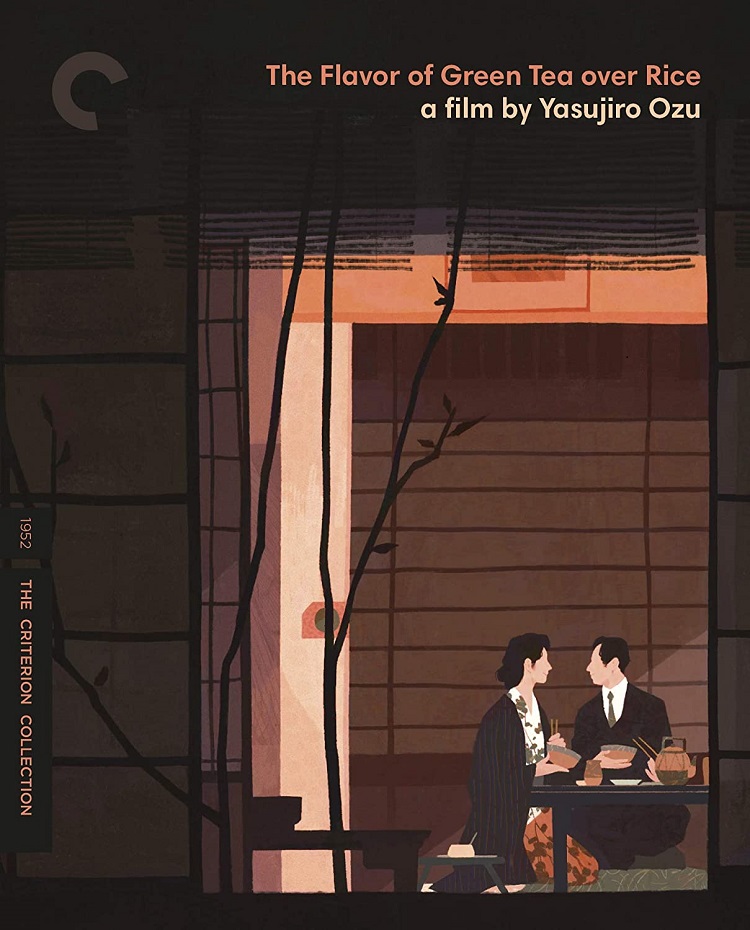

The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice has been released on Blu-ray by the Criterion Collection. Extras on the disc include What Did the Lady Forget (1937), in what I think is a home video debut in the U.S. There’s also a 28-minute video essay by David Bordwell, and a 17-minute video essay, “Ozu & Noda”, about the relationship between Ozu and his regular screenwriter Kogo Noda. There’s an informative essay about the film by scholar Junji Yoshida in the film booklet, titled “Acquired Tastes”.