This series of Iranian films is a trilogy in only the loosest sense, as they don’t share overlapping casts or themes. Their only real common denominators are their writer/director, Abbas Kiarostami, and their filming location of Koker in a remote, rural area of northern Iran. The later films are influenced by the first film, especially since they explore the effects of a devastating earthquake that occurred after the first film, but there is no narrative throughline tying them together. Taken as a whole, they paint a picture of a region in transition, grappling with modernization and disaster recovery as old norms give way to the future.

Where Is the Friend’s House? is delightfully simple in its setup: a schoolboy mistakenly takes his friend’s notebook home and desperately tries to return it to its owner before their teacher follows through on a threat to expel the friend at school the following day. That basic premise allows Kiarostami to explore the relatable theme of a child attempting crisis management in spite of unhelpful adults and no clear way to solve his dilemma. While the boy knows the general area where his friend lives, he has no way to contact him or determine his exact address, leading to an increasingly desperate solo voyage through unfamiliar communities as he races against nightfall to complete his quest.

Kiarostami used local schoolboys for the film, giving it a warmly authentic feel. The lead actor does a great job of conveying his exasperated drive to set things right without overplaying anything, keeping his character’s emotions at bay. The film suffers a bit from some character interchanges that drone on for too long, especially when the boy tries to explain his plight to his unsympathetic mother over and over for seemingly 10 minutes while she just keeps telling him to do his homework, but overall the film is a charmer and holds up very well as Kiarostami’s international calling card to the film world.

And Life Goes On builds on both the first film and the chilling effects of a massive earthquake for a plot centering on a director and his son returning to Koker to try to determine the fates of the real-life families and schoolchildren that appeared in Where Is the Friend’s House?. It’s a great concept, with the added complexity of being a loosely plotted faux documentary starring real actors rather than a straight documentary starring Kiarostami, and yet its execution is fairly dull. The characters succeed in their objective, but there’s very little narrative payoff since that objective is simply to locate survivors and document the destruction.

Through the Olive Trees further blurs the line between fiction and reality by briefly featuring the lead actor and his friend from Where Is the Friend’s House? appearing as themselves, not characters, as well as featuring Kiarostami playing a local Koker actor, all while being directed by an actor playing a director role clearly based on Kiarostami. That gleeful upending of expectations is perhaps the film’s best aspect, as its actual narrative rewards are once again fairly anemic. The basic plot centers on a director returning to Koker to produce a new fictional film while also exploring the offscreen relationships and motivations of his actors. This results in extensive making-of scenes that go on for much too long, especially one featuring Kiarostami the actor performing take after take at the bottom of a set of stairs, as well as uninvolving “interviews” with the actors behind the scenes discussing their hopes for the future. While Kiarostami’s clever intentions and setup are exceptional, the resulting film fails to move any emotional needle.

At the time of the first film’s production, Kiarostami was a virtual unknown on the international stage, so it’s fitting that he returned to the Koker area for further work after Where Is the Friend’s Notebook? announced him to the global market. Each of the films further burnished his international prestige, and while only the first one connected with me, the trilogy is still a fascinating overall portrait of an artist exploring and refining his craft.

All three films have been restored from the original 35mm negatives in new 2K digital transfers and include uncompressed monaural soundtracks. While all three films have been thoroughly scrubbed, with extremely clean image and sound quality throughout, Where Is the Friend’s House? exhibits a great deal more film grain than the other two later and presumably better-financed films.

The bonus features are extensive in length, not quantity, with only two features for each film. Where Is the Friend’s House? includes Homework, a newly-restored feature-length documentary by Kiarostami where he interviews schoolkids about their thoughts on school, discipline, and playtime. Filmed just two years after Where Is the Friend’s House?, it serves as a fitting bookend to that film, and while it overstays its welcome with a seemingly unending stream of interviews, it retains its power as an interesting time capsule. The disc’s other bonus feature is brief 2015 conversation between Kiarostami and programmer Peter Scarlet.

And Life Goes On also includes a feature-length documentary, but this one is a career retrospective about the director entitled Abbas Kiarostami: Truths and Dreams. Although there’s a bit too much reliance on extended scenes from his films, the interview segments with Kiarostami do a fine job of revealing his thoughts on his career. The sole other bonus feature is a new interview with a film scholar.

Bonus features for Through the Olive Trees are easily the weakest of the three, with just two 15-minute features. Both features are new interviews, the first with Kiarostami’s son Ahmad and the other with two film scholars. Since the first two discs contained archival work both by and featuring Kiarostami himself, these brief features that only discuss Kiarostami are largely letdowns, although both do share some interesting insight into his career.

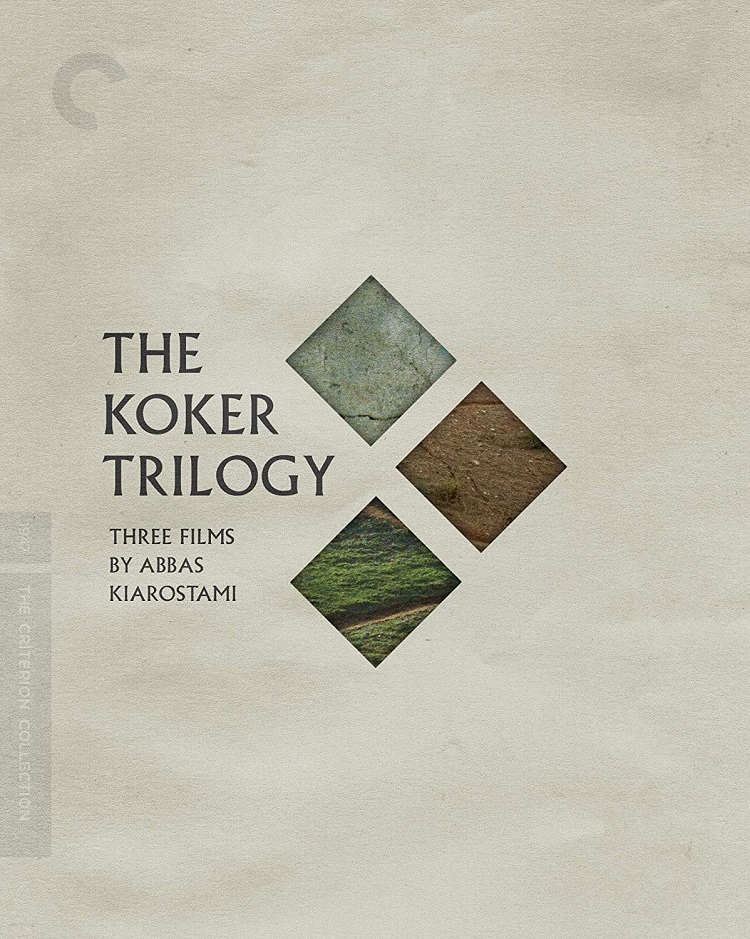

The packaging for the set is really unique, with each disc being housed in independent casing that folds out and separates into three individual gatefold cardboard cases. The cases are housed inside each other like Russian nesting dolls, with each cover containing a piece of the artwork that fills the cutout diamond-shaped windows on the box. Much like the trilogy itself, each disc is its own discrete item, but relies on the other two to complete the full picture of Koker.