From a very early age, Alfred Hitchcock knew he wanted to be in the filmmaking business. He read the trade papers and went to the cinema and knew that’s what he wanted to do. He landed his first job in the industry at age 20 in 1919 as a title card designer. From there, he began co-writing scripts and working as an art director and then a production manager. By 1922, he was set to direct his first film, Number 13, but financing ran out after only two reels had been shot and production was shut down. Sadly, all footage of that film has been lost. Undeterred, Hitchcock continued to work in the industry moving from the Famous Players-Lasky studios to Gainsborough Pictures where he worked closely with director Graham Cutts as a set designer and producer.

In 1925, he was given another opportunity to direct a film, The Pleasure Garden. It was a commercial flop but studio head Michael Balcon liked Hitchcock and gave him other opportunities to direct. With The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog, made in 1927, Hitchcock has his first hit and his first true “Hitchcock Picture.” In that same year, he signed to the new British International Pictures where he became the highest-paid director in England. He made nine films for BIP including Blackmail, his first “talkie” picture. After his time at BIP, his star rose quickly. He made several more films in Britain, including hugely successful films such as The 39 Steps, The Man Who Knew Too Much, and The Lady Vanishes. In 1939, he signed a contract with David O. Selznick, moved to America and became the beloved Master of Suspense. But it was his time at BIP where he honed his craft, and while most of those films are little known outside of Hitchcock lovers, and to tell the truth aren’t all that good, they are a hugely important part of “The Hitchcock Story.”

As part of the 2012 Olympics in London, the British Film Institute launched what they called the Save the Hitchcock 9 Project. They sent a message throughout the world to find the best prints of nine of Hitchcock’s surviving silent films (sadly, no copies of The Mountain Eagle have yet to be found) and set to cleaning them up as best as possible. Once completed, the restored films toured theaters and are now slowly making their way to the Blu-ray format.

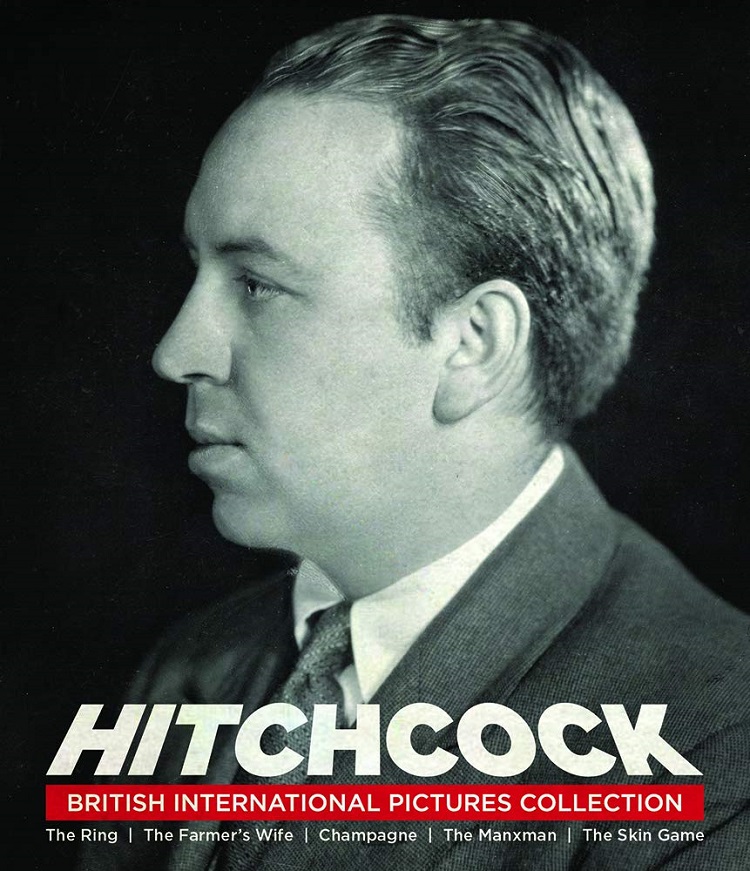

With Hitchcock: British International Pictures Collection, four of these newly restored films have recently come to Blu-ray via Kino Lorber. The films included are The Ring, The Farmer’s Wife, Champagne, The Manxman, and inexplicably, as it is not part of the Hitchcock 9 nor has it been cleaned up or restored, The Skin Game. These films represent an artist in the making. He was a director for hire, not necessarily making the films he wanted to and was not given full reign to do as he likes. They are not what we’ve come to expect from a Hitchcock picture and do not contain the types of plot elements – suspense, crime, and wrong-man motifs – generally associated with the great director. They generally fall under the genre of melodrama and all but The Skin Game are in some way romances. Each film has at least a few Hitchcockian flourishes and it’s easy to see how working without sound, in an entirely visual medium, helped him create the creative style he would rely on for the rest of his career.

The Ring is the most interesting film in this set. It is the only film in which Hitchcock receives full writing credit (though in his audio commentary, film critic Nick Pinkerton suggests that Eliot Standard, who wrote all of Hitchcock’s other silent films, likely had a hand in it). The story is simple – a fairground boxer moves up the circuit with the help of the Australian Heavyweight champion, both fall in love with the same girl – but there are enough visual flourishes to keep it exciting. Early on, there is a nice moment in which the ticket taker outside the boxing tent opens a flap to reveal what’s going on inside, creating a nice image within an image. Inside the tent, Hitchcock manages to not show much of the actual fight but instead gives us a view of the back of the spectator’s heads to great effect. During the climactic battle inside The Royal Albert Hall, he uses the Schüfftan Process – in which a box containing images of a larger set are drawn leaving one side empty in which the actors are filmed giving the illusion they are somewhere they actually aren’t.

It is here I must note that I am not a silent film aficionado. It is probably the largest hole in my cinematic knowledge. I’ve seen a few silent films, but not enough to really get ahold of how best to watch them. It may seem obvious but while watching these films, I came to realize that silent pictures aren’t just without spoken dialogue but all sound, save for the musical score, is missing. So in a film such as a The Ring, we do not hear the thwack-thwack of two men punching each other, nor the roar of the crowd, only the twinkling of the piano. It is surprising how much I rely on the sound of film to keep me interested. I had to repeatedly will myself to watch these films as my mind kept wandering away not being drawn in by the audio.

It is for this reason that I likely enjoyed The Skin Game more than I perhaps otherwise would have. Being able to follow a story through spoken dialogue and the foley effects after watching so many films without them no doubt boosted my opinion of it. Certainly the story – about two families squaring off over a piece of land – does not deserve much praise. At least, it allows for some drama that isn’t dependent on romantic notions.

The three films in this set that were made between The Ring and The Skin Game – The Farmer’s Wife, Champagne, and The Manxman – were all director-for-hire type setups and were all essentially disowned by the director later in life. When discussing them with Francois Truffaut, Hitchcock seems to dismiss them, noting that Champagne has no story at all and the only thing interesting about The Manxman was that it was his last silent film. I can’t say I disagree.

The Farmer’s Wife is another love story, this one ostensibly a comedy, but one that failed to make me laugh. It’s about an old farmer who decides he ought to marry again after his first wife has dies and his only daughter leaves the home for her own matrimonial bliss. He marches up to several women, puts his proposal to them plainly, and is tossed out for his trouble. The humor is mostly visual, such as a scene in which the servants’ feast on the food once the party guests have all gone outside – har har!

Champagne is so slight that it came into existence because a producer decided that since the alcoholic beverage was so popular then surely a film with that title would bring in an audience. Hitchcock’s initial rags-to-riches-to-rags story was thrown out and you can tell he was not too keen on being forced to change it to a riches-to-rags-to-riches story. It is worth watching for the interesting visuals that bookend the film – in which the characters are seen through a champagne glass and wonderful performance by Betty Balfour.

Interestingly, Champagne as presented here may not be the Champagne originally shown to audiences that Hitchcock had approved. The only existing copy of the film is from what is called the second negative. In those days, a film might have a second print consisting of takes and edits not deemed quite good enough for the first print which would be the one sent to theaters. This second print was designed as a backup in case the original print was lost or destroyed (or lit up in flames as nitrate prints were likely to do in those days). We have no way of knowing how different this existing print is to the original print Hitchcock approved.

The Manxman is another love triangle in which two guys battle it out over the same girl. She clearly loves one of them but had made promises to the other one and this in an age in which a girl must keep her promises. It is mostly plainly shot but there are a few shots in the Isle of Man that are quite beautiful and some subtle moments – such as when the champagne set out slowly goes flat while everyone waits on the girl to return home – but mostly it’s quite dull both in story and the direction.

For the most part, this collection looks astoundingly good. The four silent films all look fantastic. There are the occasional problems with debris and the like, as one expects from films as old as these, but truly, the degree of which they have been cleaned and spruced up is remarkable. The Manxman, on the other hand, looks quite bad. As noted, it was not part of the Hitchcock 9 program and thus was not given the restoration as the other films were. There is quite a lot of debris and scratches, and it is jittery and unstablalized in several scenes. In one scene the framing is bad with the heads of the actors nearly cut off. For the silent films, new scores have been written and recorded.

Extras include audio commentaries by film critics and historians for all the films except The Skin Game and The Farmer’s Wife. They are quite informative, giving a lot of background information and details on the actors and the making of each film. Each disk includes audio excerpts from the long discussions Hitchcock did with Francois Truffaut.

These five films are of huge importance to cinematic history and the life and work of Alfred Hitchcock. While they may not be the most Hitchockian of his films, nor even that good, their importance is second to none.