Hard sci-fi differentiates itself from the other kind by trying to follow the rules of physics and take place in a universe that might actually occur. Which doesn’t mean the story is necessarily dry or dull, but it tries to be plausible. Moon (2009) certainly doesn’t explain all of the scientific advancements that would make the story possible, but it keeps up at least the pretense of realism.

How it achieved this and more is described in the lovely new book, Making Moon by Simon Ward. Taking a linear approach, Ward follows director Duncan Jones from his early ambitions to break out of the advertising world into feature film-making, along with his friend and producer Stuart Fenegan. Both were experienced in making commercials, and wanted to move to Hollywood to advance their careers into cinema, but not without a calling card. Initially, that was going to be Mute, and Duncan actually met Sam Rockwell while casting that film, which didn’t get made until just last year, 2018. Jones knew he wanted to do something in sci-fi, and something that was like a thoughtful ’70s film in the vein of Silent Running, with a very limited cast and number of locations.

Eventually, he came up with the idea for Moon, wrote a 20-page treatment, and on the strength of that began to put together his crew. Simon Ward has interviews from all of the principals of the cast and various crews, including the production team, the special effects crew, and the miniature effects group, with the various aspects of the production getting a chapter each in the book. Sam Rockwell’s performance is, of course, singled out in a chapter of its own.

Moon was a challenge to get made, for a relatively small budget and with a short window of time when Sam Rockwell would be available. But it was not what one would call a troubled production. The story in Making Moon is not about creative clashes or an underdog bucking the system, nor Hollywood excess and a tyrannical director. It is about serious professionals with a lot of hope, and a number of people doing their best to help them out. When Duncan Jones and Stuart Fenegan asked their investors if they could start spending money, even without a distribution deal in place and with absolutely no guarantees that money would ever be made back, the investors said, “Sure.”

Luck was also a contributing factor to Moon turning out as well as it did. Right when the film was moving into production, the 2007 WGA strike began. Neither Duncan nor Stuart were in the WGA, so they could keep working at Shepperton Studios, and even expand to some other sound stages for free because most of the rest of the local productions had to shut down. The strike also freed up the schedules of some experienced crew to be able to work on the film. Moon was still a grind, as any film and especially a low budget one has to be, but Duncan, from all accounts, kept his hands dirty in the production. For instance, since there was only one miniature set, Duncan and visual effects supervisor Gavin Rothery would spend four hours a night mucking around in the moon dirt (really kitty litter) to create a new moonscape for the next day’s shooting.

The film’s debut at Sundance ended up being bittersweet – all the distributors who’d turned down the film back in preproduction were now interested in bidding, when it had already been sold. Moon ended up being released in July of 2009, and while it was no kind of hit, apparently it made back its money. The film’s box-office performance is diplomatically not discussed in the book, which rightly focuses more on the cultural impact of the film. But Moon turned out to be just the calling card Duncan Jones was hoping for, and has led to a feature filmmaking career. Stuart Fenegan remains his production partner, and has kept with Jones through Source Code, World of Warcraft, the recently released on Netflix Mute, and their upcoming comic book adaptation, Rogue Trooper.

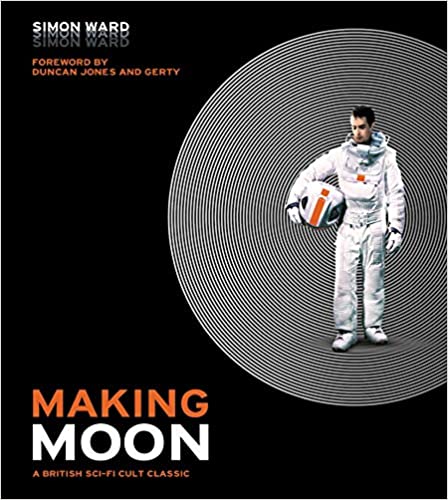

Making Moon is an impressive book physically. It’s lavishly illustrated with photographs, sketches from preproduction, and includes several script pages covered with markings with directions and ideas for shooting. In the chapter on Clint Mansell’s haunting score, there is even a couple of pages of sheet music. The book is a sturdy oversized hardcover, measuring 10 by 12 inches, and 144 pages long. The cover recreates the movie poster image of Sam Rockwell standing in front of concentric circles representing the moon, and embossed, forming an interesting texture. It’s a coffee-table book for film fans, and would make a fine gift for any enthusiast of Moon. It is just that: an enthusiast’s story of the making of a great science fiction film. It’s not a critical evaluation, nor does it have any pretense to be. Making Moon is a fine addition to a film fan’s library, and for Moon enthusiasts, it’s hard to find a reason not to own it.