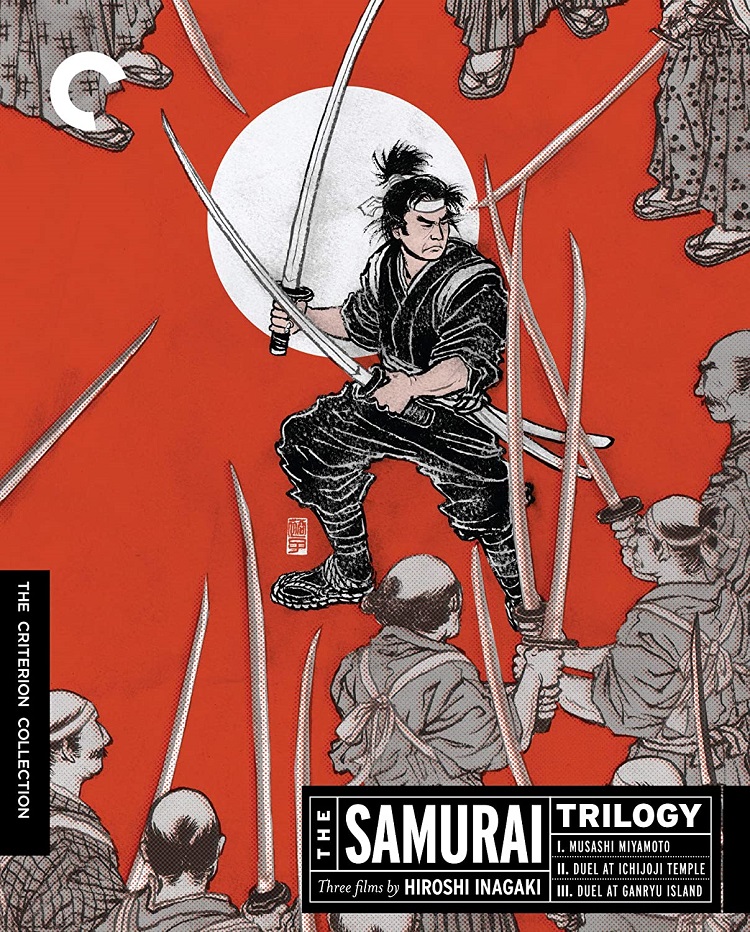

Japanese screen legend Toshiro Mifune is most closely associated with the directorial efforts of fellow legend Akira Kurosawa, and yet he actually made more total films with lesser-known director Hiroshi Inagaki. The Samurai Trilogy represents three of the Mifune/Inagaki collaborations: Musashi Miyamoto, Duel at Ichijoji Temple, and Duel at Ganryu Island. Although the films were released separately over three years in the 1950s, they are each part of one continuing story about the life of the 17th-century swordsman Miyamoto, so in effect the trilogy is one epic five-hour movie. While the trilogy doesn’t get much attention in the U.S. today, it’s worth noting that the first film won the Academy Award for best foreign film.

Mifune plays the title character, and it’s a treat to see him in his physical prime in this project that commenced right after his work in Seven Samurai. This is a young, fit, tough Mifune, believable and menacing in his swordfight scenes and dashing in his romantic interludes. As Miyamoto, he admirably tracks the character’s path from an undisciplined teen brawler to an enlightened and seemingly unbeatable 29-year-old warrior. The character is one of Japan’s most well-known folk heroes, and Mifune’s considerable charisma makes him an ideal match for the legend.

The love story in Miyamoto’s life seem to be more tacked on than essential to the overall plot, which is the project’s lone detractor. Miyamoto is solely focused on perfecting his swordsmanship, in spite of his requited love for a devoted girl from his village named Otsu. Throughout the trilogy, she crosses paths with him and begs him to abandon the sword and the warrior’s life for her and domestic bliss, but Miyamoto can’t be swayed. He also lands a less-desirable stalker in the form of fellow warrior Sasaki, who becomes such a central figure by the final film that he almost dominates it. Sasaki has both great respect and contempt for Miyamoto’s skills and vows to defeat him, setting him up as the chief rival of the trilogy.

Without paying attention in advance, I expected a 1950s Japanese samurai project to be filmed in black and white, so I was pleasantly surprised to discover the breathtakingly rich original color palette presented in these restored films. To be clear, the colors have that slightly washed-out look indicative of Eastmancolor film stock of the era, not the searing vibrancy of today’s hi-def efforts, but that only added to the production’s allure in my opinion. Colors are consistent and precise throughout the films. The new digital transfers were created from 35mm low-contrast prints struck from the original camera negatives and further burnished to near-perfection via the removal of defects and jitter. As for audio, the mono soundtrack sounds great, with consistent levels and no noticeable hiss. This is another top-notch Criterion restoration, even on DVD.

Bonus features are fairly unimpressive, only including new interviews with a historian about the real-life Miyamoto along with some trailers. Still, the films speak for themselves and are well worth seeking out in this stellar package.