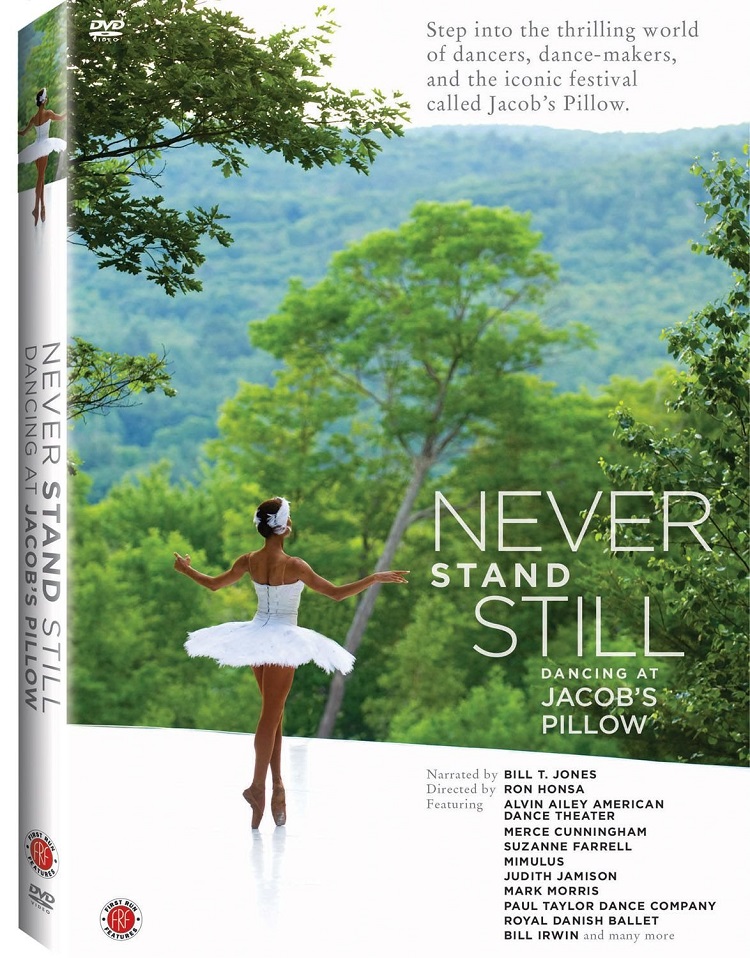

Director Ron Honsa, whose television and film credits range from nightly news specials to Saturday Night Live to America’s Most Wanted, has spent many years using his talent as a filmmaker to support and uplift the dance community by directing dance for television. In 1985, he released his documentary The Men Who Danced, which chronicled the evolution of Jacob’s Pillow founder Ted Shawn’s all-male American company, Ted Shawn’s Men Dancers. Now, in Never Stand Still, Honsa explains what became of Shawn’s rustic farm in the Berkshires of Western Massachusetts that he purchased in 1931, initially as a retreat where the injured could heal themselves through creative movement.

Along with a host of icons and up-and-comers from all corners of the dance world, narrator Bill T. Jones, lauded choreographer, dancer, theater director, and writer, leads viewers through 74 minutes of frank discussion and highly diverse dance festival footage that get to the heart of why Jacob’s Pillow has thrived well into this, its 80th season. There’s the exuberant Mark Morris hailing the Pillow as a place that champions different people from different places, and the various styles of dance they bring. And if it’s never explained in the film exactly why Shawn chose the majesty of Nature over the bustle of the city to construct his very own mecca of dance, Morris puts it plainly: “You’re in the woods. You have to dance—that’s it.” Then there’s Suzanne Farrell, legendary Balanchine ballerina and current artistic director of Washington D.C.’s Suzanne Farrell Ballet, recollecting about the time she spent at the Pillow in the mid-1970s and the experience of having her company perform there in 2006. In a rather poignant moment, she says that to study and perform at the Pillow is to feel “the dust” of the dancers that came before.

The most interesting part of the documentary, however, is listening to artists more mainstream dance aficionados may not recognize recount their experiences while preparing to perform at the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival. Rasta Thomas and his company Bad Boys of Dance are shown scurrying to pull a full-length show together in the space of two weeks. In another scene, he and his troupe receive last-minute feedback about their program in a cozy dressing room graffitied with messages and signatures from other dancers who struggled to infuse even more meaning into their work in the minutes before its debut. It’s Thomas’ view that to get everyday people, not just patrons, immersed in dance, you have to have a hook; and making dance entertaining is paramount to its livelihood.

From Thomas, to Merce Cunningham, to Judith Jamison, to Australian contemporary dance company Chunky Move and Indian dancer Shantala Shivalingappa, dancers of all walks gravitate to Jacob’s Pillow because they consider it an equal-opportunity dance festival that promotes dance not only as one’s life’s work, but a serious profession. And it consistently draws audiences that want to be there to be exposed to new forms of dance, as opposed to attend an event. Honsa’s work successfully illustrates how an organic setting is conducive to creating new talent and germinating ideas into great works of art. It also shows how versatile this rural location can be—so much so that it can accommodate choreographers’ most elaborate visions. Ted Shawn said, “Dance is the only art of which we ourselves are the stuff of which it is made.” After watching this, dancers and non-dancers alike will have a clearer understanding of how and why it’s made.