Both Kinji Fukasaku and Takashi Miike were unlikely survivors in their different eras of Japanese cinema. They both were highly prolific, and rare among their peers when the fortunes of the Japanese film industry turned for the worse, they kept working, pivoting into different genres and styles. Fukasaku worked steadily through the ’70s and ’80s when many of his peers fell by the wayside, and though Miike by all rights ought to have burned out with his amazing productivity (over 100 feature films in three decades of filmmaking, sometimes more than five in a single year) he’s still going strong.

And both filmmakers have tackled the yakuza genre. Much of Kinji Fukasaku’s ’70s output was yakuza films, most notably his extensive Battles Without Honor and Humanity. These were a deliberate attempt to tarnish what Fukasaku found the puzzling mystique of the yakuza. These were criminals, low-life, predators, violent outliers in Japanese society, and in films they tended to be anti-heroes. In his films, they just tended to be creeps.

Miike’s yakuza films have been more varied and even fantastical, and rarely have any of the documentary-style realism that Fukasaku affected. And both men made their own versions of Graveyard of Honor, adaptations of a novel by former yakuza Goro Fujita, whose own story was the inspiration for the Outlaw: Gangster series.

In Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor (1975), the star of that series Tetsuya Iwari returns to Fujita’s gangster world. Here he plays Riki Ishikawa, the main character of Graveyard of Honor, and if Fukasaku’s yakuza movies were designed to reduce sympathy for gangsters, Ishikawa seems designed to make them appear absolutely loathsome. Based on a real-life figure, the film has some semi-documentary aspects with audio interviews with his relatives playing over photographs of (ostensibly) the real-life Ishikawa in his youth. These give no real insight. There is no real insight. Ishikawa is just a violent, dangerous psychopath, bringing a whirling cloud of violence where ever he ends up, hurting foe and friend alike. His career starts just after the war in 1946, and he weaves a path of destruction for about a decade. After a raid on an enclave of “third nation” types (Chinese and Korean refugees in Japan who had no love for their former Imperial masters), Ishikawa hides from the police in a geisha house, taking one of the girls, Chieko, captive. He promptly rapes her, tosses her some cash, and forces her to hide a gun for safe-keeping. Of course, in inimitable weird Japanese cinema style, she falls immediately in love with him.

Ishikawa goes from once horrible incident to another, instigating violence, nearly starting a gang war, and eventually, after serving a stint in prison for slashing up his own godfather, becoming an exile from yakuza society for 10 years. An hour into the film, where he’s becoming a junkie and sponging off former friends, I began to wonder why the hell I was watching this dreary, depressing person’s story.

I didn’t have too much time to wonder, though, because Fukasaku’s incredibly kinetic filmmaking style doesn’t leave the audience much time to collect their breath. Fights are often shot with handheld cameras, moving in improbable angles with the action chasing back and forth with wild confusion. Parties and orgies are weirdly even more frenetic, with body parts and booze passing before the camera in a practically kaleidoscopic fashion. There’s copious violence, often accompanied with spurting geysers of that deep red ’70s Japanese movie blood that looks completely unreal and absolutely disturbing.

It’s riveting, at times, and the world of ’40s and ’50s Japan the film conjures is completely convincing. In keeping with the documentary style of the film’s opening, several scenes are filmed in sepia, marking out significant milestone in Ishikawa’s short, turbulent, horrible little life. But I was left cold in the end, still not sure why I needed to see this story.

If Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor left me with confusion as to how I was to receive it, Miike’s 2002 version left me almost completely blank. While it tells a similar story (the protagonist, so-called, this time named Rikuo Ishimatsu) it is not quite a remake of the 1975 original but a re-adaptation of the source material, updated for the Japan of the late ’80s to the mid ’90s, where the economic bubble of 20th century Japan peaked and burst.

The main characters have some similarities in their potential for violence, their ill use of friends, and their ability to find the exact wrong target for their grievances and the exact wrong time and method of addressing it. But Miike’s Graveyard has no pretense toward documentary realism. We don’t get any insight to Ishimatsu’s childhood, or any sense that there’s much of a person there at all. He’s working at a restaurant when a gunman (in a fun cameo by director Miike himself) comes in blazing, and Ishimatsu knocks him down with a chair, saving a yakuza boss’s life. He’s brought into the yakuza, immediately made a boss, and just as immediately he makes a violent nuisance of himself. It’s not long before he has attacked senior members of the yakuza, and after a misunderstanding puts a bullet in his boss.

He plays out some other scenes similar to the ’75 film, most grotesquely in the similar relationship with his own Chieko, whom he rapes and declares to be his wife. She’s traumatized into accepting it, and seemingly becomes devoted to him, and her own eventual self-destruction. It’s not a lot of fun.

The point of contention is not that there isn’t a redeeming quality to Ishikawa. The very point of the character is his irredeemable nature – he’s a broken cog being fixed into a wicked machine, which is then perplexed why he keeps spitting sparks and smoking. And while Miike finds all kinds of arresting displays of his sociopathic extremes (maybe the best is the scene where, fully doped up, he slides around his apartment on his back, finding his mass of hidden guns and firing them into the ceiling) it doesn’t amount to a portrait that’s either relatable, instructive, or edifying. It’s gross. It’s mean to be gross. I do not know why I’d want to watch it.

Because, like I’d said earlier, it’s not a lot of fun. The film lacks much of Miike’s redeeming energy and bizarreness. Without the over the top scenes that are too outlandish to be taken seriously in so many of his other films, Graveyard of Honor is mostly played straight and the grimness of the violence can become overbearing. One notable exemption, and maybe my favorite scene in the film, is an extended shootout between the police and Ishimatsu, when they’re finally tipped off to his whereabouts. He stands on his balcony, strutting in his underwear, grabbing guns from a large pile and firing them off into the crowd of police, who only cower. Eventually, ammunition exhausted, he grabs a white shirt and starts waving it in the air. “I’m out of bullets,” he shouts, matter of factly, like it was a game and he’d just run out the shot clock, a couple of points down.

Taken individually, many of the scenes of the film have their own fascination, but together there’s an emptiness to the core. Which, again, might be the point, since the performance Goro Kishitani as Ishimatsu it ferociously focused. Ishimatsu doesn’t have a large pallet of emotions – he tends to switch from blank to sullen, and when other emotions threaten to arise they sit on his expression like unwelcome guests. It’s an impressive performance.

Very different in their execution and only vaguely similar in their storylines, these two Graveyards of Honor are thematically similar: both are about what a concept like “honor among thieves” mean when they are extended to creatures that can neither reciprocate nor understand honor. Miike and Fukasaku have taken their source material and molded them to their times: the desperation and striving of the post-war era and its recovery, and the excess and bloody minded business practice of the late 20th century boom and bust. They’re both dark and fascinating films. I do not think I liked them very much.

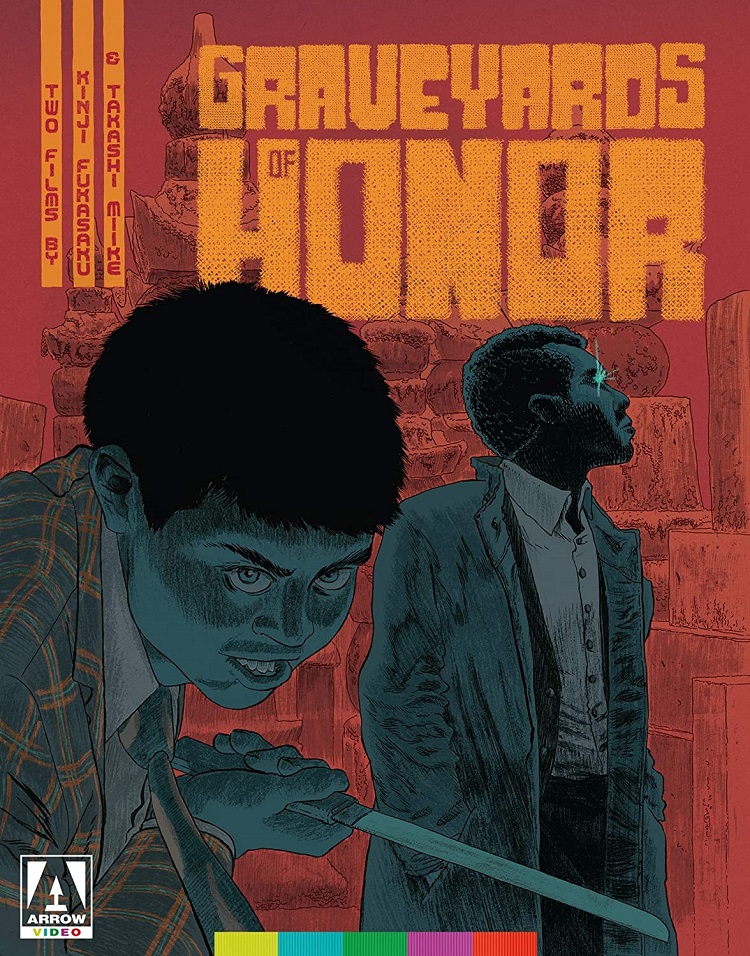

Graveyards of Honor has been released on Blu-ray by Arrow video. The set contains both Fukasaku’s and Miike’s films of the same name, made in 1975 and 2002 respectively. Each disk contains a number of extras. For the Fukasaku film: an audio commentary by Japanese film expert Mark Schilling, a new video essay by Projection Booth podcast host Mike White, “Like a Balloon: The Life of a Yakuza” (13 min), and some archival extras: “A Portrait of Rage” (20 min), a Japanese short about Fukasaku’s films, “On the Set with Fukasaku” (6 min), a vintage featurette, and a trailer and image gallery. The Miike film disc contains the following extras: an audio commentary by Miike expert Tom Mes, and a new video essay by critic Kat Ellinger, “Men of Violence: The Male Driving Forces in Takashi Miike’s Cinema “(24 min). There are also archival video extras: an “Interview Special” (18 mins) with Miike and some of the cast, a “Making of” (8 min) featurette, a “Press Conference” (5 min), a trailer, and image gallery.