When Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City (1945) won the Grand Prize at Cannes in 1946, he was recognized as the de factor leader of the Italian Neorealism movement. His Paison (1946) and Germany, Year Zero (1948) completed his War Trilogy, and cemented his position. For his Italian countrymen, who were in the process of trying to come to terms with the aftermath of the Mussolini dictatorship of World War II, his unflinching eye for the real world was not what they wanted to see. In some respects, Rossellini himself felt this way, as is indicated by his statement that he was “tired of filming in bombed out cities.”

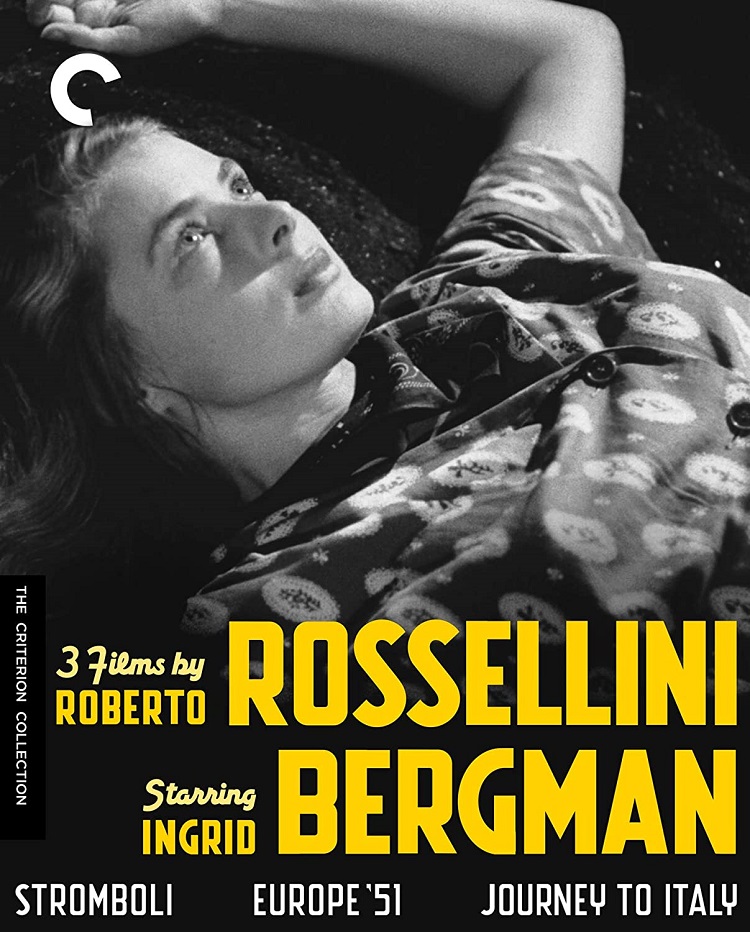

Rosellini’s next phase would be called his “Journey Trilogy,” and include Stromboli (1950), Europe ‘51 (1952), and Journey to Italy (1954). All three films star Ingrid Bergman, who became his leading lady in life as well. The films have been packaged in a new five-DVD set from the Criterion Collection as 3 Films by Roberto Rossellini Starring Ingrid Bergman. If the War Trilogy made Rossellini an instant hero with the critics, the Journey Trilogy made him a pariah.

The old saying “Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned” comes to mind, especially after viewing the different versions of these films. There are scenes in them that would later be acknowledged as classic Neorealism. Yet they were overlooked at the time in favor of the more dramatic charges of “sellout.” The overriding sensibility may be melodramatic, but this was Rossellini. For one thing, he was pioneering a style that was clearly ahead of its time. In these films, the real subject matter is the inner turmoil of the lead character, played by Bergman in each film.

Sixty years ago, the events surrounding the filming of Stromboli colored everything about it. The involvement of Bergman with Rossellini began with a fan letter she wrote to him, in which she expressed a strong desire to work with him. He could hardly say no, and thus began their scandalous affiliation. Both Rossellini and Bergman were married to other people at the time filming began. By the time it wrapped, she was pregnant by him.

Life imitated art here. In the opening shot, we see Karin (Bergman) living in a post-war refugee camp. Her only way out is to marry a POW sailor named Antonio (Mario Vitale), who she has just met. They move to the place he grew up, a sparsely populated island in the Mediterranean. Karin hates this place with a passion, and while it is grim, she does seem a bit petulant about the whole thing.

To give the critics of the time their due, Stromboli is very melodramatic. But the vitriol it was received with had to have more to do with the extracurricular activities of the actress and director, because it is not that bad. As for the charges that he had “abandoned” Neorealism, watch the amazing scene with the men netting tuna in the ocean. It is fantastic. One of the most amazing things that happened during filming was an actual volcanic event on the island. The evacuations scenes of the island residents are as “real” as it gets.

The differences between the two versions of Stromboli are especially apparent during the final scene. In the English-language version, the ending is full of hope. I would call it a Hollywood ending. It is not as garishly optimistic as actual Hollywood movies of the time, but it is upbeat. The Italian-language version is much more vague as to what Karin and her unborn child will do after surviving the eruption. I am sure that is the one that Rossellini felt closest to, although according to some of the notes, he felt the film was never properly finished.

There are three bonus features on the English Stromboli. The first is Rossellini Under the Volcano (1998) in which director Nino Bizzarri visits the island 50 years after the film was made. Among the people he interviews are members of the cast, surviving villagers, and the man who played Antonio, Mario Vitale. (45 minutes).

“Surprised by Death” is a visual essay by film critic James Quandt. In it, Quandt examines the various connecting themes of Stromboli, Europe ‘51, and Journey to Italy. This piece was created in May 2013 for the Criterion Collection. (39 minutes).

There are enough differences between the Italian-language version of Stromboli and the English one for Criterion to include both of them in this set. One of these is the running time. At 106 minutes, the Italian version is six minutes longer than the English version. As mentioned earlier, I felt that the most substantial change between the two comes at the end, with the pregnant Bergman pondering her fate. In the Italian version, we are left to make up our own minds as to what the future holds for her. This is Rossellini’s cut, apparently the English version was edited “by others.”

The first bonus feature of this second DVD features an interview with film critic Adriano Apra, recorded in 2011. Apra discusses the themes of Stromboli, and the huge scandal that surrounded its production in the spring of 1949. (16 minutes).

For 3 Films by Roberto Rossellini Starring Ingrid Bergman, Apra is Criterion’s resident expert and appears in interviews for all three films. The second supplemental feature on the Italian-language version of Stromboli is Rossellini Through His Own Eyes, which is Apra’s documentary about the director. (60 minutes).

Rossellini and Bergman were married (to each other) for the filming of Europe ‘51. It is the most political of the three, and is even a bit heavy-handed at times. Bergman stars as Irene Girard, a woman whose life with wealthy husband George is a whirlwind of glamour. When their son attempts suicide, they are told that it was for attention. The self-absorbed couple continue to ignore the son, and his next suicide attempt is successful. Irene then has a moment of clarity, and feels guilty about her narcissistic life of luxury.

This is certainly a noble premise for a film, especially one by an Italian director whose country was still digging out from the nightmare of life under Mussolini. Things get a little overwrought at times though. There are nearly enough speeches to make this a left-wing answer to Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead.

As in the case of Stromboli, the set features the English and Italian versions of the film. The English Europe ‘51 has a running time of 109 minutes; the Italian is 118 minutes. Also very much like Stromboli, the biggest difference comes in the final frames.

Everyone around Irene is concerned for her sanity. This is where the “message” is really brought home. She has been taken to a psychiatric facility to find out what is wrong with her. One of the men in charge puts the question rather bluntly, “Are we dealing with an absolutely insane woman, or a missionary?” he says to George. It is as if both conditions are equally dangerous. In the English version, there is a long closing scene of her upstairs in a room, standing at a barred window, and waving to the people outside. They are all shouting “Goodbye.” It is obvious that she will not be coming out any time soon.

In the Italian version, the final scene is visually the same. But instead of saying “Goodbye,” the people in the crowd are saying, “She is a saint.” Two very different takes on the “problem” of a Good Samaritan.

There are three bonus features on the English DVD of Europe ‘51. The first is another 2011 interview with Apra, which focuses on this film. (18 minutes). The second is an interview with fraternal twins Ingrid and Isabella Rossellini, recorded in March 2013 for the Criterion Collection. (31 minutes). The third extra is My Dad is 100 Years Old (2005), which was directed by Guy Maddin. In this tribute to her father, Isabella Rossellini plays every role, including Federico Fellini, various critics, and both of her parents. (17 minutes).

The bonus features on the Italian-language version of Europe ‘51 are also quite intriguing. In “The Tragedy of Non-Conformism,” critic Elena Dagrada discusses the differences between the two versions of the film. (36 minutes). G. Fiorella Mariani is Roberto Rossellini’s niece, and recorded this interview in March 2013. It is quite good, and even includes some vintage home movies (15 minutes). The third and final supplemental piece on the disc is The Chicken (1953), a short Rossellini – Bergman film. (16 minutes).

Journey to Italy is the final film of the trilogy. There is only one version of it, in English. Journey to Italy could be Scenes from a Marriage (1973) twenty years earlier. Well, not really. But the marriage between Katherine (Bergman) and Alex Joyce (George Sanders) is the basic subject matter. Sixty years later, we are no longer shocked by the affairs that Alex and Katherine engage in. Journey to Italy even has a heartwarming conclusion, which I am sure that the American distributors appreciated.

Living and Departed is the first bonus feature. It is a visual essay by Rossellini scholar Tag Gallagher in which he discusses Journey to Italy in relation to Stromboli and Europe ’51. (23 minutes). Apra completes his series of 2011 interviews about the films for the second supplemental piece (11 minutes). A Brief Encounter with the Rossellini Family is a little promo film about the family during the filming of Journey to Italy (five minutes).

Ingrid Bergman Remembered (1995) is a very substantial documentary, and is hosted by her daughter from her first marriage, Pia Lindstrom. (50 minutes). Finally, what major Criterion Collection release would be complete without some words from Martin Scorsese? He sums up the Journey Trilogy as being “where modern cinema begins,” among other fascinating insights in this 2013 interview. (11 minutes).

Scorsese’s opening remark about the Journey Trilogy is “What do you do after you have changed the way the world looks at cinema?” He also mentions that with Stromboli, Rossellini was part and parcel of his nation’s search for an identity after the horrors of the war. To divorce these films from their place in history is completely misguided, although that is exactly what the critics attempted to do.

Context is everything, and nobody does a better job of providing it than Criterion. All tolled, the five films here add up to about eight and a half hours, while the supplements are just over six and a half hours. Add the 85-page book, and you have a set that truly defines the term “definitive.”

After watching these films, there is no denying that Rossellini did occasionally lapse into the melodramatic. But so what? There is a lot more to them than just the Bergman characters’ various tribulations. Next to Criterion’s previous War Trilogy set, this is an absolute must for anyone with an interest in the legendary director.