Terry Gilliam lives to be idiosyncratic. In a British comedy troupe, Monty Python, he was the American. In Hollywood filmmaking, he seeks to be the European auteur. His entire oeuvre is about outsiders and misfits. He is an outsider and misfit. And so, his sell-out film, his bow to Hollywood, desperate for work, happens to be about the ultimate outsider and misfit.

12 Monkeys is about a man out of time and space. Or about an insane man. James Coles (Bruce Willis) believes he has been sent from the future to gather information on a virus that wipes out almost all of humanity. When he arrives at an insane asylum in 1990, he’s disappointed, because he’s six years too early.

He tries to explain this to his psychiatrist, Kathryn Railly (Madeleine Stowe). She’s intrigued and feels a connection to him that she can’t explain. She assumes he’s delusional and believes that he can save humanity. But no, he says this has all already happened. He’s just there for information.

Humanity begins to die in 1996, so the scientists of his time sent him back too far. “Science ain’t an exact science with these clowns,” a disembodied voices tell him when he’s restrained after an escape attempt.

That attempt was facilitated by his only “friend” in the asylum, Jeffrey Goines (Brad Pitt). When watching a documentary about animal testing, James muses that maybe humanity deserves to be wiped out by a virus. Goines hears, and might agree, because he subsequently forms the army of the 12 Monkeys. It’s a terrorist organization that in the future is believed to be the cause of the outbreak that ends humanity.

That’s one of the main targets of Jim’s information finding… according to a panel of scientists from the future. Who might be all in his head. 12 Monkeys plays with the notion that Jim’s harbinger of doom might be reality, or it might be an actual insane delusion.

Except that several aspects of the story demonstrate that Jim has actual foreknowledge of the future. But then there’s the disembodied voice that calls him “Bob” and gives him advice that it’s never clear if it’s useful.

12 Monkeys is a science fiction film, and a thriller. And it might be a movie about mental illness. Its premise comes from a French art film, La Jetee. 12 Monkeys, which has action and violence and glib humor, is still in essence a kind of art film. It’s just nothing like its French progenitor.

It is a Terry Gilliam film. And Gilliam wants things to look interesting. Function is far less a consideration than form. Jim from the future lives in an underground world, where everything should be austere, but the scientists in control have elaborate constructs and devices. When Jim is interrogated, he’s held in a chair that climbs up a wall, and the scientists look at him through a probe with multiple video screens. This is impractical. It’s silly. But it looks neat, and creates the atmosphere that Jim is under the control of “scientists” who aren’t under the control of themselves. So it works visually, and that’s Gilliam’s chief concern.

Because though 12 Monkeys is ostensibly science-fiction, it is not a work of the mind. It’s a work of the heart. There’s an intelligent story, but the central tragedy is of a man, either from the future who knows the present is dead, or a mad man who has convinced himself of this. There’s no real hope. His life is futile.

That’s the emotional core of the film, and of Bruce Willis in what might be his best performance. He’s a big guy, a tough – much is made of his fighting off cops and putting them in the hospital with his bare hands. But he’s also spent most of his life in the underground, completely disconnected from any of life’s pleasures.

After kidnapping Dr. Railly in 1996, Jim listens to the radio and the music it plays like a child, hearing things for the first time. It’s an affecting performance, particularly in contrast to the obvious violence Jim is capable of and demonstrates.

12 Monkeys works on so many levels that it’s hard to find one point of entry. It’s satirical and sincere at the same time. It can find room to make fun of its concerns (societal decay, environmental degradation, animal experimentation) while taking them seriously, too.

There’s a wonderful scene near the end of the film where James is hiding out in a theater playing Hitchcock’s Vertigo. He says he saw the movie as a kid on TV, but it seemed so different then, because he’s grown and he’s different. The experience of watching 12 Monkeys is the same. When I first saw it (on a preview weekend before it opened wide) all of my sympathy was with the James Cole character. Watching it now, nearly 30 years later, I found myself closer to Dr. Railly, who has to deal with her world unraveling with the introduction of this chaotic man who cannot be telling the truth… but who also cannot be denied.

The 4K release of 12 Monkeys is based off a newly scanned print of the film. Some scenes have an amazing new clarity… though some of that clarity just makes the graininess of the original film more clear. I have no issue with film grain and no particular love for “smooth” video images if they’re not part of the film’s vision. And Terry Gilliam’s style usually involves occlusion, distortion, and odd film images. It’s not an issue to me.

12 Monkeys is Terry Gilliam’s most successful film, financially. I think it might also be his best artistic achievement. Some might look at Brazil, but as much as I love that film, it doesn’t integrate its fantasy and “reality” segments as smoothly. The subjective and objective are more easily delineated. In 12 Monkeys, you never know if the film is a time-travel story or a mental-illness story. You have to take it as both at once, which gives a power and a poignancy to both of the main character’s tragedies.

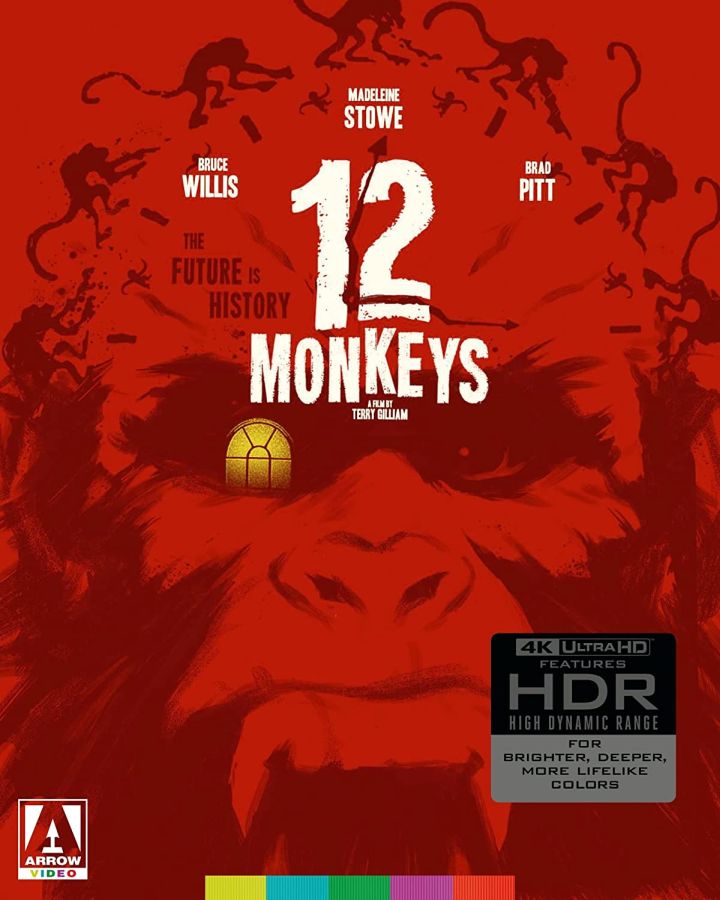

12 Monkeys has been released by Arrow video on 4k UHD. Extras include a commentary track by Terry Gilliam and producer Charles Roven. “The Hamster Factor and Other Tales of Twelve Monkeys” (88 min), a great feature length documentary on the making of the film, filmed contemporaneously with the production; “The Film Exchange with Terry Gilliam” (24 min), an interview with Gilliam filmed in 1996; “Appreciation by Ian Christie” (17 min), an video essay by Christie, writer of Gilliam on Gilliam; the “12 Monkeys Gallery”, an image gallery, and a theatrical trailer.