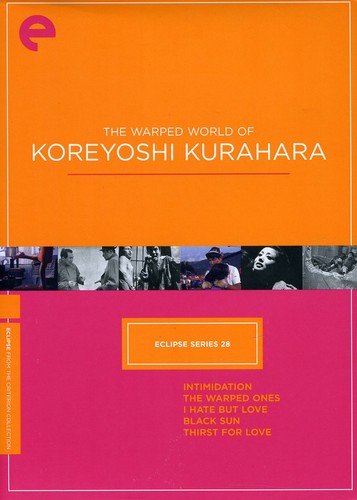

Watching the five films in Criterion’s latest Eclipse offering, The Warped World of Koreyoshi Kurahara, one gets the sense that Kurahara was a filmmaker with wildly diverse interests. The films in the set careen from tightly wound noir to jazzy, anarchic buddy movie to erotic art house fantasy — and yet, each seems to be the work of a master of the genre. We’re not talking about a “jack of all trades, master of none” situation here. Kurahara didn’t just dabble; he embraced every genre shift with gusto.

Working at Nikkatsu studios in the 1960s, Kurahara was a prominent figure of the Japanese New Wave, and while his name might not ring bells like Nagisa Oshima or Seijun Suzuki, this set has the kind of films that could remedy that if more people saw them.

The five films included are:

Intimidation (1960)

Barely running over an hour, Kurahara doesn’t need much time to mount an increasingly anxious crime thriller laced with concerns about class relations. Takita (Nobuo Kaneko) is a banking official about to be promoted to the head office. His charisma stands in direct contrast to the meek Nakaike (Akira Nishimura), a boyhood friend who’s been a stepping stool in Takita’s professional and personal life.

But when Takita is blackmailed with proof of his corruption, he takes drastic measures to protect his career, including plotting a robbery on his own bank. Kurahara deftly shifts the pieces and ratchets up the tension, and the film’s power reversal finale is marvelously executed.

The Warped Ones (1960)

The equivalent of a cinematic rebel yell, The Warped Ones bristles with dangerous energy, taking the New Wave’s sense of stylistic anarchy and turning it all the way up.

Tamio Kawachi stars as Akira, a juvenile delinquent taken to jail for pickpocketing. When he gets out, the jazz-obsessed youth embarks on a spree of rape and violence with pals Masaru (Eiji Go) and Fumiko (Noriko Matsumoto) while looking to take revenge on the journalist who helped put him away.

There’s nothing restrained about The Warped Ones, and Kurahara’s commitment to cinematically matching the unpredictable angst of his lead character makes for a dizzying experience. Its portrait of utterly amoral behavior can be undeniably grating, but at only 75 minutes, the film is packed with enough woozy, jazzy stylistic punches that it becomes unforgettable in a good way.

I Hate But Love (1962)

A radically different film from the one that precedes it, I Hate But Love saw Kurahara putting his stamp on the romantic comedy, aided by one of Japan’s megastars at the time, Yujiro Ishihara. He plays Daisaku, an enormously popular radio celebrity, constantly at odds with his manager, Noriko (Ruriko Asaoka).

The two are clearly in love, but she’s not willing to commit to him physically and he’s not willing to commit emotionally, and their relationship exists in a tension-filled limbo that one could easily imagine Kate Hudson and Matthew McConaughey slipping into in the American remake.

But for all of its melodramatic, ridiculous rom-com flourishes (and there are plenty), there exists a weird undercurrent of unease and even violence beneath the surface. Matters are complicated when Daisaku decides to flee his life of fame, at least temporarily, to deliver a jeep to an impoverished village in the name of humanism and pure love.

Compared to the rest of the films in the set, I Hate But Love stands as easily the most mainstream, but there are plenty of oddball edges that a Hollywood studio would have to sand down today to fit the commercial model, and those edges make the film a small delight.

Black Sun (1964)

A sort-of sequel in spirit to The Warped Ones, Black Sun lives up to the packaging’s description that you’ve never seen anything like it before. Kurahara cranks up the surreal as Tamio Kawachi stars again as Akira (although, this time he goes by Mei). Whether or not it’s the same character, the love for jazz lives on, and Mei’s makeshift home in a bombed-out church is covered with posters and records of black jazz musicians.

When Mei meets an actual black man — Gill (Chico Roland), an American GI wounded, wanted for murder and carrying a big-ass machine gun — he’s exuberant, proclaiming that he loves all black men because of negro jazz. But Gill doesn’t really care; he’s just trying to survive, and the resulting culture clash shatters Mei’s world.

Scored by jazz drummer Max Roach (one of Mei’s heroes in the film), Black Sun funnels the outrageous energy of The Warped Ones in a different, more ambiguously bizarre direction and its bleak, deranged vision of postwar Japan is truly like nothing I’ve ever seen.

Thirst for Love (1967)

An adaptation of the novel by Yukio Mishima, Thirst for Love pulses with erotic tension. Ruriko Asaoka stars in a markedly different role than in I Hate But Love as Etsuko, a widow trying to mesh with her late husband’s wealthy family. She’s fallen into a sexual relationship with her father-in-law (Nobuo Nakamura), but secretly lusts after the young gardener Saburo (Tetsuo Ishidate).

Kurahara’s film is relentlessly interior, delving into the mind of Etsuko as she seeks to reconcile her desires and her behavior. He uses a variety of techniques, including interior monologue, mysterious narration, dreamlike fantasy segments and even occasional flashes of color to portray her fragmented state.

Thirst for Love was Kurahara’s final film as a contract director at Nikkatsu and capped off a decade of incredibly varied work.

The Warped World of Koreyoshi Kurahara is the 28th release in the Eclipse line, and the set features four sharp, detailed black-and-white transfers and one reasonably strong color transfer for I Hate But Love. Intimidation has a transfer issue that causes a tiny digital shudder at almost every cut, and this is fairly bothersome, if not too intrusive. What appears to be the same issue pops up a few times during Black Sun as well, although it’s not nearly as frequent. Each disc is accompanied by an essay by critic Chuck Stephens.

Overall, this is another winner from Criterion’s Eclipse line that offers a much-needed introduction to a major member of the Japanese New Wave.