There are two things most vintage movie buffs will instantly think of whenever Alan Ladd’s name is mentioned: the movie Shane and the word “short”. Originally rejected by the very industry that later made him a star due to his height and extremely blonde hair, one has to wonder if that didn’t spawn some sort of Napoleon Complex with the actor. Indeed, after becoming a force to be reckoned with in 1942’s This Gun for Hire as a tormented assassin with a damning moral sense of right and wrong, Ladd managed to escalate to his own victory as the drifting, walking mystery of a man called Shane in what has since gone on to be one of American cinema’s most acclaimed westerns.

Alas, it wasn’t enough – or so it would seem. Unhappy with the powers that be at Paramount, Ladd left to shoot a trio of films for future James Bond producer Albert R. Broccoli in the UK before returning to America to start up his own production company. And it was with 1954’s Drum Beat that Ladd’s new Jaguar Productions began to make a number of independent films under his own personal guidance, completely free from any of the usual oppressive tyranny studio executives probably forced upon him. Of course, just like when Napoleon decided he could conquer Russia all on his own, Ladd’s final say over his own projects would eventually begin to show signs of a certain kind of madness.

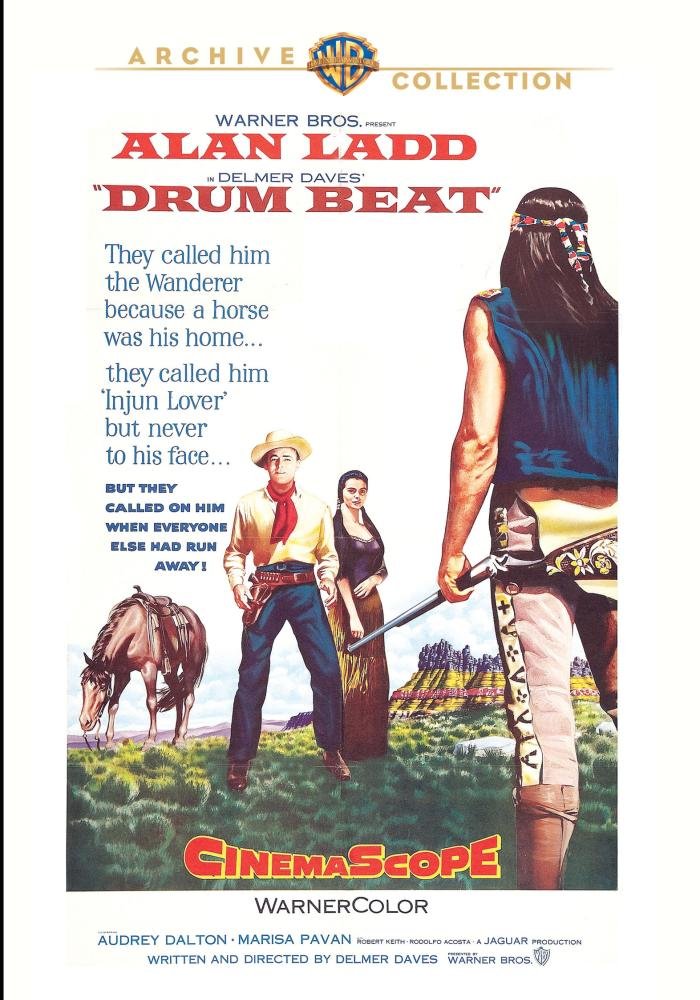

But I’ll get to that in a little bit, folks, believe me. First up is the aforementioned Drum Beat – a western adventure released by Warner Brothers that showed a great deal of promise from Jaguar Productions, and which even based its story on actual events. Set in 1872, our story opens with frontier Indian fighter Johnny MacKay (Ladd) being asked to lay down his gun in favor of representing his government and President Grant (Hayden Rorke) as peace commissioner with the Natives.

An easy task for sure, right? Wrong – since the restless Natives in question are the faction of renegade Modoc warriors as led by the notorious Kintpuash, better known to the world of relatively obscure local history buffs as Captain Jack (Charles Bronson, using his new last name for the first time in his very first starring role), who is only interested in waging war with the white man since they, you know, killed a bunch of ’em and relocated the rest to the least-hospitable area around. But poor Johnny tries his best to reach the rogue chief, narrowly avoiding death just about every time they meet. In fact, you might just say that this Captain Jack character has something of a Death Wish goin’ on here. (Sorry.)

Meanwhile, our dashing, adventurous, intrepid, and ever-fearless Ladd has to bring in the traditional “boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl in the end” motif that was extremely popular then. When the story required it, that is. Of course, in the case of Drum Beat, such a subplot actually works in favor for not only Ladd’s character, but the story itself. In fact, Ladd actually has two love interests here: young Audrey Dalton – as the niece of a local retired colonel who gets slaughtered by the “bad” Modocs – and young Marisa Pavan as a lass from the “domesticated” Modoc tribe. But of course, there can’t be any interbreeding in this ’50s production, so you can guess which girl the older man chooses.

But that’s beside the point: apart from a number of historical inaccuracies and the fact that they didn’t actually film the tale in Modoc County (where not a lot has changed over the last couple of decades), Drum Beat emerges as an entertaining film. Veteran character actors Robert Keith, Elisha Cook Jr., Anthony Caruso, Frank Ferguson, Frank DeKova, George Lewis, and Strother Martin also star.in this entry from writer/producer/director Delmer Daves, who also wrote and/or directed a number of notable entries in the genre, including the original 3:10 to Yuma and the neglected Shakespeare in the Wild West production of Jubal (which also featured Charles Bronson).

Moving on a few years and a few Jaguar Productions down the road, we find ourselves at the tail end of the 1950s, wherein Ladd’s filmmaking army had already started to wane. Having made the huge mistake of declining to take the part of Jett Rink in Giant two years earlier (a part that ultimately went to James Dean, and which has since gone down in history as the doomed ’50s icon’s final film), Ladd’s very own undiagnosed Napoleon Complex probably began to increase. His popularity in the industry was now diminishing, his desire to seek solace within the confines of a bottle began to rise, and that once-young face from whence that golden hair grew started to grow increasingly puffier.

But of course there was nothing to stop him from making more movies for his own production company, right? In fact, it was just about all the little Ladd had. Thus, in 1958, Warner Brothers released another of Ladd’s Jaguar Productions efforts, The Deep Six – which, thankfully, is not a precursor to the equally-slow cheesy ’80s sci-fi flick Deep Star Six, but rather a World War II drama. A slow-moving World War II drama, to be concise, and one that features a number of day-for-night shots that are clearly daytime (did someone forget to color filter those scenes for the DVD, or is that how it’s supposed to be?).

Beginning with one extremely lengthy look at our lead character’s backstory – which could have easily been trimmed some – we meet (and subsequently stare at for a very long time) advertising agency artist Alec Austen (Ladd, lookin’ a bit puffy), who woos co-star his boss (Dianne Foster) at great length by luring her into his beach home to show her his etchings (seriously, he actually uses that line in one of the film’s better scenes as Ladd’s character verbally flips through a proverbial bachelor’s how-to book). Nevermind the fact that she’s engaged to her boss, she’s his, darn it! Why, the man even takes her home to meet his mum (Jeanette Nolan), whom we learn is a Quaker – thus, so is Alec by his upbringing – just to get her approval to marry the already-called-for woman.

Then, finally, Ladd reveals what we, the audience, have known for the last twenty minutes: that he’s been called into service from the reserves – something his Quaker mother and half-assed half of a would-be fiancée are not entirely thrilled to learn – and is not-so-promptly shipped to the seas under the command of James Whitmore. Frankly, I can think of no better actor to serve under in the Navy, with the exception of Joe Besser, of course. Alas, no Besser here, but his frequent television employer Joey Bishop is onboard, as a womanizing sailor (in what was obviously a bit of a stretch for Bishop). Also on deck here are William Bendix, pediatrician Efrem Zimbalist Jr. (in a wonderfully sublime performance), and cult movie favorites Richard (Rocky Jones, Space Ranger) Crane and Robert (The Hideous Sun Demon) Clarke.

But it can’t be all fun and games when there’s a worldwide war going on – even in the Navy. After all, there are Nazis and Japanese soldiers out there in the waves. But worse than that, there’s a spiteful, hateful lieutenant commander -as played by the great Keenan Wynn – onboard, determined to pay those diabolical Axis partners back for eliminating his family at Pearl Harbor – and who has a bad feeling about Alec’s Quaker anti-violence background, whilst attempting to conceal his own health problems from everyone else. As it turns out, though, Wynn is right about that weird feeling in his gut directly next to his tumor: when the time comes to fire upon the enemy, Alec can’t commit to committing murder – even if it’s in the name of liberty, justice, and (hopefully) the pursuit of a much better-written role in a major studio production somewhere.

As time – and the movie’s snail-like pace – rolls on, our soldier with a damning moral sense of right and wrong (wait a second, where have I heard that before?) even winds up getting his one and only good friend in the whole of the entire United States Navy killed because he can’t pull the trigger. And then – in the very next happy scene – the not-even-slightly-despondent artist meets his bride-to-be (who has since learned she would rather love the guy signing her paychecks) with a finished painting of his late pal, which he intends to happily take to a now-fatherless eight-year-old girl somewhere in Iowa. Happily. The subplot about Wynn’s stomach cancer? Gone. (Happily.) The feller Ms. Foster was previously engaged to before? We never see him again after the opening scene.

And if you think Napoleon Ladd might have misjudged his own damning moral sense of right and wrong for the sake of getting the girl and leaving the audience with a wrongful feeling of a happy ending, just wait until you wander out in front of the Guns of the Timberland, kids!

This, the second-to-last offering from Jaguar Productions, also proved to be one of the last films Ladd ever made, and here, the level of facial puffiness has increased to the point where it looks like the poor guy fell washed his kisser with fish oil after having a rhytidectomy during the midst of an allergic reaction to the medicine he was taking for a dental abscess. Ensuring he gets most of the closeup shots by his lonesome – you know, just to show us he’s still viable and not at all short or anything – Ladd and his lumberjack lads (or Ladds, I suppose?) arrive in a small western town (the film was shot in Plumas County, California) during a precarious point in history before there were telephones, but frontier musicians had somehow mastered 1950s-style rock music.

And who’s that singing the delicately crafted throwaway jukebox ’50s ditty bearing the incredible title (and lyrics) of “Gee Whiz Whillikins Golly Gee” (wait, isn’t that about what Fluke Starbucker says when he’s handed his D-cell flashlight in Hardware Wars)? Why, it’s future Beach Party sensation Frankie Avalon, boys and girls! And Frankie is in fine tune as always here in his very first starring role. He even gets the illustrious “Introducing” subcaption for his opening on-screen credit, as the producers of Jamboree! evidently failed to do so three years prior (though this is his first acting credit, so I guess it’s OK). Ladd’s non-actress of a daughter Alana (really?) even has one of her few roles in the movies here as Avalon’s girlfriend.

But back to the story, kids. So then, Ladd and his company of loggers – including Noah Beery Jr., stuntman Paul Baxley, and a slew of other mostly uncredited burly-looking dudes – come to town on the choo-choo, boisterously singing a song about chopping down trees, drinking whiskey, and womanizing whilst their miserable wives are back at home. They then wonder why nobody wants them around – a strange case of antisocial behavior to blame on the fact that the townsfolk know darn well that removing the trees above them will cause their peaceful little community to turn into another ghost town. Why there’s one such place just a few miles away that local rancher villainess Jeanne Crain takes Ladd to in order to illustrate their point.

Naturally, as is usually the case when two rivals get together in a depressing ghost town in Plumas County, there’s some lust in the dust as our questionable excuse for a hero and the decidedly mislabeled malefactor (or is that femalefactor?) of the tale somehow find the time manage to strike up a rocky relationship with each other despite the fact that they are mortal enemies and stuff. But this doesn’t stop her from dynamiting the main trail up to the mountain, or blasting her own trees down in order to prevent the loggers from accessing the source of their potential income when he decides to fight fire with fair – and asks the government for as easement. Ladd’s partner (Gilbert Roland) has different ideas, however, as he seems to be the only one who observed the movie – as well as its advertising artwork – promotes said Guns of the Timberland.

Thus, a brief (disappointing) sort of war ensues, which culminates in one of the biggest out-of-left-field romantic endings ever, wherein the previously powerful and fiercely-independent Crain suddenly shows up at the railroad station as the loggers depart to give up everything she has worked so hard for – save for her hatbox and toiletries case, of course – to join her one true love, to wit Ladd proudly says that he gets to call all of the shots from thereon in. But it all makes sense once you observe Aaron Spelling’s name in the credits and the fact that the story was based on one of the fifteen-kazillion novels written by the prolific western pseudonym of Louis L’Amour. Lyle Bettger and Regis Toomey also star in what is arguably not one of Ladd’s finest films.

Regrettably, Alan Ladd’s health began to deteriorate as the early ’60s progressed, resulting in a failed (alleged) suicide attempt in 1962 (he was found in a pool of blood with a gunshot wound to the chest, and that’s about all that’s said on the subject), as well as his (reportedly) accidental suicide in 1964 as a result of too many sedatives washed down with alcohol. Ironically, his eventual return to Paramount Pictures resulted in her very own Waterloo, The Carpetbaggers (released several months after his death in ’64) – which actually proved to be one of the biggest hits of the year around the world. In fact, so popular was Ladd’s part in the groundbreaking motion picture that year that studio heads ordered up a prequel – one that replaced Ladd with yet another doomed icon: Steve McQueen as Nevada Smith.

Now, while Ladd’s health (mental and physical) can be seen becoming frayed around the edges as the overall story quality diminishes over the course of this line-up, you can’t argue over the fact that the Warner Archive Collection has made these Alan Ladd titles available for contemporary home video audiences at last. Another, fourth Jaguar/Ladd film – The Big Land – was also released by the Warner Archive at the same time, and half of the four released titles are new to home video period. And they’re all in their original widescreen aspect ratios – which, in the case of recommended Drum Beat, is a nice pretty CinemaScope presentation. Audio-wise, these manufactured-on-demand titles feature clear mono soundtracks, and the reviewed picks above are barebones releases.

(The Carpetbaggers is also available from the Warner Archive Collection along with several other Ladd films should you wish to give the late star-crossed cinematic Napoleon a proper movie-viewing send-off, though I do heartily recommend Drum Beat as a viewing option.)