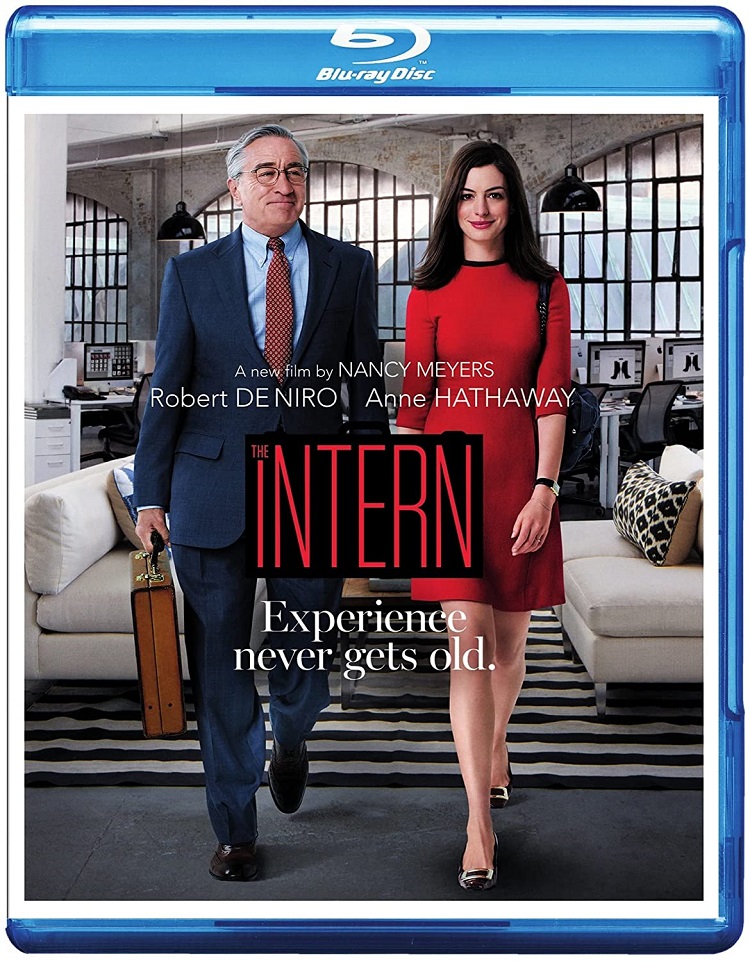

I realize that criticizing a Nancy Meyers movie for being unrealistic is rather like criticizing maple syrup for being sticky. But The Intern goes far beyond the pleasant fantasies propagated in the Jack Nicholson-Diane Keaton romance Something’s Gotta Give and the Meryl Streep/Alec Baldwin/Steve Martin love triangle It’s Complicated. The new movie, starring Robert DeNiro and Anne Hathaway, is selling a version of “feminist empowerment” that would be laughable if it weren’t such a toxically attractive fantasy.

First let me get out of the way the counter-argument: that I am being a politically correct curmudgeon, using a sledgehammer to whack a carefree little comedy that wants to do nothing more than entertain. I plead guilty with extenuating circumstances.

Since as far back as 1980’s Private Benjamin, which she co-wrote with her then-husband Charles Shyer, Meyers has specialized in the not-terribly-difficult problems of rich, privileged white people. There’s nothing wrong with that in and of itself; dozens upon dozens of sitcoms have mined the same territory since at least I Love Lucy, and screwball comedies featuring wacky heiresses lit up the silver screen before that. If that’s what works for Meyers – and what sells tickets – you go, girl.

But The Intern is one of those Meyers movies, like Baby Boom and a bit like Private Benjamin, where Meyers is focusing on the female character’s work-life balance rather than just her love life, as in Give and Complicated. Essentially, The Intern asks: can Anne Hathaway’s e-commerce wunderkind Jules Ostin have it all – satisfying (and lucrative) career, loving husband, adorable little daughter, and the undying loyalty of her customers and employees? Well, with the help of still-dapper 70-year-old DeNiro as the titular intern, Ben, she can. (I’m not even going to bother saying “spoiler alert” because you can chart all this movie’s plot points by watching the trailer.) Its very familiarity and predictability is one of its biggest selling points.

Let me stop again and answer the question: did I enjoy watching this movie? I went on a discouraging, lonely day, looking for something silly and stupid and yes, predictable, to pass a few hours. I admired the charm and skill of the two leads (I still have trouble thinking of scary Robert DeNiro as charming, but actually it was his charm that made his psychopaths truly frightening – there was always something appealing about them even at their creepiest.) I left the theater feeling that I had gotten the movie experience that I had sought.

It wasn’t until the next day that the memory of the movie’s fakeness and too-comforting lies began to bother me, and to seem less like a meal composed entirely of cotton candy (not nutritious, likely to cause a tummy-ache but not actively harmful), and more like an attempt to pass off wax fruit as an edible snack. It looks like feminism combined with entertainment, but it smells, and tastes, like nothing.

The arc of the plot is that overstretched entrepreneur Hathaway is so dedicated a micromanager that she personally approves each day’s home page for the online clothing retailer she founded less than two years before, visits the warehouse to train the grateful-looking employees there how to correctly wrap a package, and even occasionally answers customer service calls.

What she is not so good at is the actual managerial stuff: you know, the boring, non-screenplay-friendly activities of a company president, like making budgets and meeting with venture capitalists and chairing dull meetings. Her CFO, Andrew Rannells, wants her to bring a professional CEO on board to give the fast-growing but still-young company some “real” business cred.

Needless to say, all the potential CEO candidates (who we never meet) are male. They represent the faceless patriarchy that is going to come in and be a real boss, as opposed to this silly-but-charming woman who has been playing dress-up. (And of course no matter how overstretched and sleep-deprived the screenplay tells us she is, Hathaway never looks less than fabulous.) Never mind that the company has been amazingly successful with her at the helm. Told by Rannells that “the VCs” are worried about the company’s ability to sustain its growth, she cries (and not for the last time in this movie) and says “Give me CEO lessons.” That alternative, however, seems to be a non-starter.

O.K., there’s probably a little reality buried in this plot. Women in business still have to prove themselves, and prove themselves, and prove themselves, just to stay in the game. And too often they need to soften their personalities (consciously or unconsciously) to not intimidate others or to be perceived as a “bitch.”

But this nugget of truth is a big part of the movie’s problem. The screenplay says at several points what a horror Hathaway is to work for and how tough she is. (She’s resistant to having an intern at all, particularly a man old enough to be her grandfather, and likes him even less when he proves to be capable, observant, tactful and protective. He is, in fact, a Practically Perfect Person, so he’s right at home in a Nancy Meyers movie.)

Back to Jules: the problem is that despite what the screenplay says,in the playing and direction she’s nowhere near being a terror as a boss, a wife, or a mother. She doesn’t scream at people or belittle them in front of others. She’s not snide or sarcastic or even particularly brusque; her default modes are polite, apologetic, and unfocused (mainly because she’s almost constantly multi-tasking). Someone predisposed to dislike/distrust women in power might think her behavior is bad, but what happens when they meet a real-world boss who loses her temper? If Anne Hathaway is a “terror,” an actual cranky woman becomes Godzilla by comparison.

It’s true that Jules’ assistant Becky (Christina Scherer) feels overworked and underappreciated, particularly when Ben, who had a long business career prior to retirement and widowerhood pushed him toward this senior internship program, becomes not just Hathaway’s confidante and father figure but an integral part of her work team. Becky cries that she has a business degree from Penn but that Hathaway has never given her a report to review.

Well excuse me but boo-fucking-hoo. You’re an underappreciated, overqualified 24-year-old assistant? Oh my God, put you on the national news because no one has ever seen the likes of you before. And maybe one of the reasons your boss is chronically late to all her meetings is because your prime organizational tool seems to be a handful of sticky notes.

Hathaway herself is a classic passive-aggressive boss. One of the running gags is that a vacant desk has become piled high with leftover hangers, spare boxes, clothing remnants, etc. Each time Hathaway passes it (on the bike she rides through the open-plan Brooklyn loft offices! She’s so adorable!) she makes an exasperated noise and says, though not loud enough for anyone to hear, “Why doesn’t somebody clean that up? That’s driving me crazy!”

Mind you, she doesn’t scream this at anyone or do something that might actually make the problem go away like, oh, e-mailing her assistant, or one of the many other slackers around the office, to take care of it.

DeNiro, apparently equipped with mental telepathy, wins her heart by understanding her pain and taking it upon himself to clean up the desk. Her gratitude that someone, finally, “gets” her is at first heartwarming and, when considered later, pathetic. I’d also love to see the scene when somebody looks for something they left on the dump desk and has to search through the closet where DeNiro stashed everything. But in a Nancy Meyers movie, no good deed is ever punished, at least not in plain view.

The other, related plot arc concerns Jules’ marriage to stay-at-home dad Matt (Anders Holm, last seen being anally fingered by his down-low boyfriend in Chris Rock’s Top Five). Here, Holm is cheating again, but with a woman. He gave up a promising career to take care of their daughter Paige when Jules’ business took off, but (I know you’ll be shocked by this) he feels emasculated by her success, lonely because she’s working all the time, etc. Meyers is somewhat clever in tying together the CEO plot with Jules’ marital problems, the idea being that if she is less consumed by her work, she will have more time to save her marriage.

To its credit, the movie has DeNiro’s Ben point out the fallacy in this logic (he’s cheating on her, not the other way around), and reminding Jules that her business success is nothing to feel guilty about. Again, that’s what the screenplay says. What the movie shows is that you can be beautiful, smart, rich, and successful, but if you don’t massage your husband’s ego, he’ll cheat on you – and you’ll feel guilty about it.

Oh, and besides being the kind of nightmare that would make Betty Friedan wake up in a cold sweat, The Intern is also the whitest movie I’ve seen in a long time. I’d say the movie looks less like multi-culti Brooklyn than Des Moines or Lincoln, Nebraska, but these cities almost certainly have greater diversity than Meyers shows here. There’s barely a black, Asian, or Latino face in the workplace, ostensibly a tech company. Really?

When there is a hint of color, it is literally window dressing. DeNiro has two fellow senior interns who arrive on the same day he does, an older white woman named Doris (Celia Weston) and an African-American identified on IMDB only as “Senior Intern” (G. Keith Alexander). “Senior” has no lines and is never seen again, which may be preferable to how Doris is portrayed. When Jules temporarily reassigns Ben, Doris shows up to drive her to work and promptly gets them into a fender-bender because she’s busy talking and not paying attention. These lady drivers!

Watching The Intern, I wondered if Meyers wasn’t trying to make a movie about her own career. She is close to Ben’s age but, like Jules, is the leader of her companies when she directs a movie – and let’s remember that financially “bankable” female film directors are still not exactly thick on the ground in Hollywood. Is The Intern her sly way of critiquing the impossible choices women in power still, unfortunately, have to make? Or is this just how she sees the world – through outdated, out-of-focus rose-colored glasses? I’m betting on the latter.