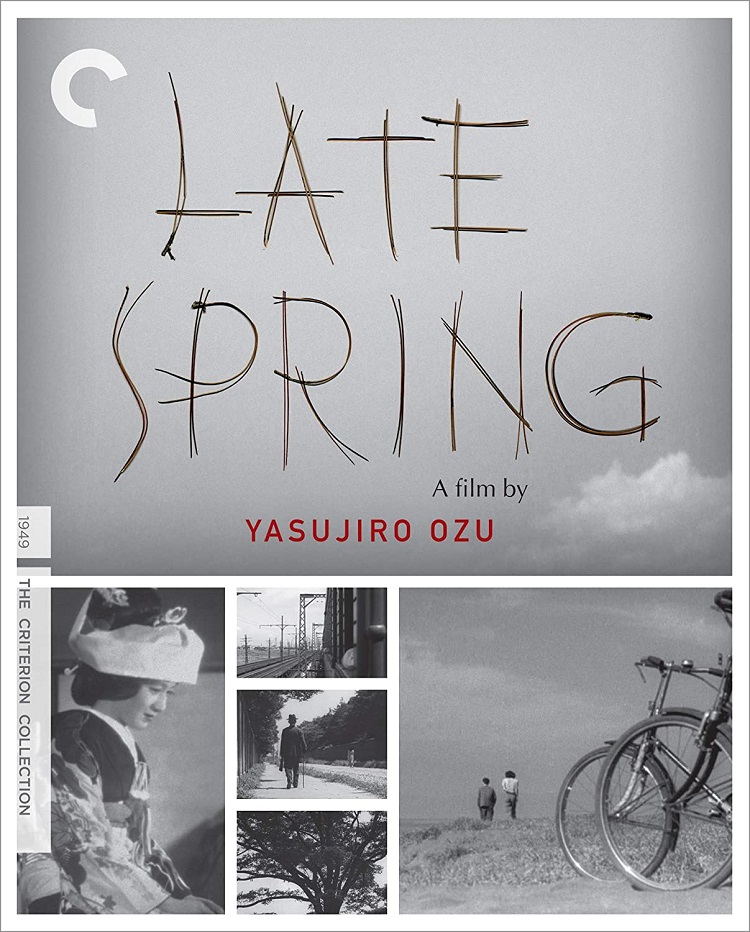

Writer/director Yasujiro Ozu is widely regarded as one of the most important Japanese directors of all time, generally second only to Akira Kurosawa, and yet widely different in style. While Kurosawa’s most popular films have exciting, memorable plots, Ozu is a master of the quiet moments of family dynamics. That approach is on full display in this winning character study of a family in transition, both due to the aftereffects of World War II and the time for the adult daughter to leave the nest. While firmly rooted in the clash between traditional Japanese culture and the modern era of independent women, the film’s universal themes make it a timeless tale still able to elicit relatable emotions in any culture.

Noriko is 27 years old but still living at home with her widowed father Shukichi, not because she’s freeloading off of him but because she wants to take care of him and has no interest in marriage. Her meddling aunt is dead set on marrying her off, convincing Shukichi that it’s the best course of action for all parties, and dutifully sets off to find a man for Noriko since she won’t find one for herself. When Noriko initially rebuffs her aunt’s attempts, a rift is opened between the generations, leading to soul-searching on both sides while the father and daughter attempt to resolve their differences.

Noriko is a modern woman, generally wearing Western clothes and expressing her opinions rather than assuming a docile position. She sees the promise of change offered by Japan’s postwar reconstruction efforts and hopes to find her own place in society rather than having it dictated to her. Meanwhile, her father and aunt cling to their old ways, wearing traditional clothes and conspiring to arrange a marriage as past generations had done. The father isn’t malicious in his efforts and seems conflicted about honoring his daughter’s wishes, but simply doesn’t know any other modus operandi.

The film takes place almost entirely at the family home, establishing the father and daughter’s harmonious daily routines as well as the discord created by the impending change. Noriko wears an ever-present smile that only fades as she finally accepts her fate to be married off. The final scenes between father and daughter are heartbreaking, with the father maintaining a joyous façade about Noriko’s impending nuptials even while she pleads with him one final time on her wedding day to allow her to stay at home. Only when the father returns to his painfully empty home does he realize what he has done, dejectedly slumping in his chair as the film fades out. As a father myself, the film hit hard and gave me an unwelcome glimpse of the future. It’s interesting to note that Ozu was similar to Noriko in real life, living with his mother his entire life and never marrying or having children.

While the film has been digitally restored by Criterion, it is still in relatively poor condition compared to the rest of their library of films from the same era, with near-constant and abundant scratches, as well as wavering contrast resulting in the darkness of black tones seemingly in flux, especially in the later stages of the film. There’s also some noticeable jitter in the final act. The Blu-ray transfer exposes these flaws in crystalline HD, marking this as a release that might actually be better served by SD presentation. I have no point of reference for how poorly the film may have appeared prior to restoration, but viewers expecting typical Criterion polish will be disappointed by this effort. The soundtrack is presented in uncompressed monaural audio as usual for mono Criterion Blu-rays.

The sole bonus item is a feature-length documentary about Ozu entitled Tokyo-ga by fellow esteemed director Wim Wenders, an enlightening look at his life and legacy.