Written by Kristen Lopez

Rewatching films of the past quite often leaves audiences saying, “This premise would never work in the era of cell phones.” Gillian Robespierre’s Obvious Child follow-up, Landline, takes this concept and runs with it, setting her story in 1995 when floppy discs were the height of technology. With instant communication delayed, characters are required to evoke precise timing when delivering hard truths. But for all its attempts to say “everything old is new again,” Landline falls into a sandtrap of being too similar to countless movies of the past and present. Neatly checking off every box in the “indie family drama” list, Landline pushes a wonderful cast of actors into playing it too safe.

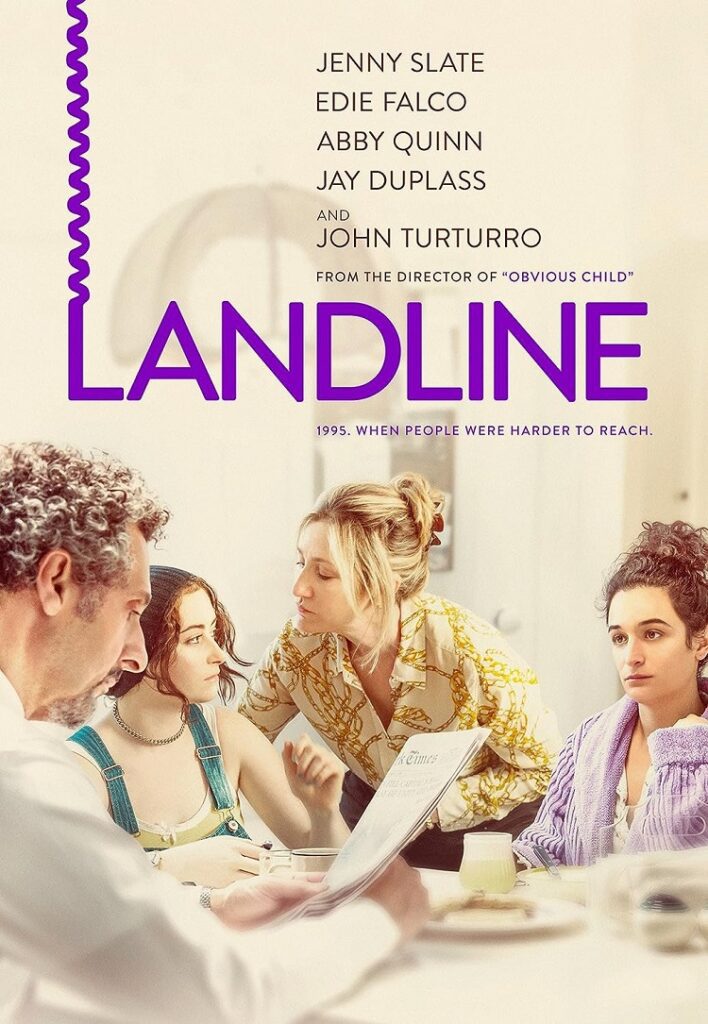

The Jacobs family are upwardly mobile New Yorkers in various stages of becoming. Parents Pat and Alan (Edie Falco and John Turturro) have a non-existent sex life and differing concepts of how to parent their wild teenage daughter Ali (Abby Quinn). Ali is experimenting with sex and drugs, and uncovers the fact that her father is cheating on her mother. The only seemingly normal one in the group is Dana (Jenny Slate) who’s set to marry her vanilla boyfriend Ben (Jay Duplass). Unfortunately Dana finds something missing in the relationship and soon enters into an affair with Nate (Finn Wittrock).

After the frisky Obvious Child, it’s hard not to use the term “sophomore slump” to describe Landline. It possesses brutal insights into what makes a relationship function, whether it be in a family setting or a romantic relationship, but everything feels hopelessly flat. One can predict the entire trajectory of the film purely off how characters problems are described. Slate’s Dana is in the typical post-college ennui we’ve come to expect from movies about upper-class New Yorkers, particularly in a differing time period. Her and her boyfriend have little to talk about, blandly shower together, and believe having “woodland sex” will reinvigorate their romance when it does little more than give Dana poison ivy. From the minute Wittrock’s Nate arrives the audience can put two and two together and have it equal “hotter sex.” The rest of the Jacobs’ clans problems are just as predictable: Ali is a rebellious teen harboring a family secret she can’t expose, and her parents are in a loveless relationship involving cheating. The fact that there are no quirky friends offering advice is the one surprisingly non-predictable element, but the lack of others in the Jacobs’ family’s cirlce only makes them appear more like they were created in a screenwriting Mad Libs course.

For a family drama t,he tension seems manufactured. Dana and Ali attempt to expose Alan’s infidelity, staking out his place of work like two inept PI’s. Their disappointment at discovering him eating a hot dog – a sin slightly less forgivable than cheating on their mom – it’s mildly funny if only undone by their completely apathetic response to seeing the woman he’s cheating with a scene later. Quinn’s Ali looks to have a plot with something passing for dramatic heft, even if it’s in the vein of after-school special. She spends her evenings clubbing and blithely tries heroin, declaring to her sister that she didn’t get addicted so there’s no reason to worry. Robespierre avoids the preachiness by avoiding the need to persecute Ali for her decisions, but there’s no grand catharsis for her character. A family dinner scene at the end leaves the audience to wonder if Ali has given up her wild ways or is just going to keep doing heroin, either scenario seems possible.

The 1995 time period could aid in the presentation of this nuclear family in an era we look back at with nostalgia. But for all audiences who grew up in the ’90s and knew about 1995, it’s hard not to see the family through similarly rose-colored glasses. The production team do their utmost to insert as many ’90s products as they can but fail to transcend anything beyond “because it’s the ’90s!” Floppy discs, references to Blockbuster and, yes, the beloved landline telephone, all make appearances but come off as gimmicks as opposed to being items an average family would have.

The frustration of the film’s plotline aside, Robespierre and crew know how to assemble a cast and Landline’s group of thespians do a lot to make up for its narrative shortcomings. Abby Quinn’s sparkling performance as Ali is the movie’s highlight. Rebellious, tempestuous and an all-around bitch at times, Quinn entices as much as she annoys. A sisterly trip to the local pool soon turns ugly when Ali can’t let of a simple splash, leaving Dana to start whining. The two sisters’ penchant for drama is on full display and Quinn perfectly plays up Ali’s dark personality. Edie Falco and John Turturro also take their stock characters and turn out lived-in performances as Pat and Alan. Turturro is especially compelling. Despite the character being the laid-back dad who can’t discipline his children Turturro’s warmth and empathy make his exhaustion easy to see. When he finally confronts Pat, Turturro demonstrates all the feelings the character’s held in for decades. Similarly Falco plays the only character with logic and a notion of responsibility. It is this need to do the right thing that aids in her overall malaise with her life. This leaves Slate in the role of “spunky ‘good’ girl.” Dana isn’t a character that’s as funny, charming or likeable as her role in Obvious Child. In fact, the character’s descent into “cheating is the only way to learn I really love my boyfriend” makes her seem like a worse person.

If you’ve watched any independent family drama in the last twenty years you’ll easily deduce the plot machinations in Landline. The cast is wonderful and it’s a shame the script feels as generic as a box of fake Oreos.