The Films

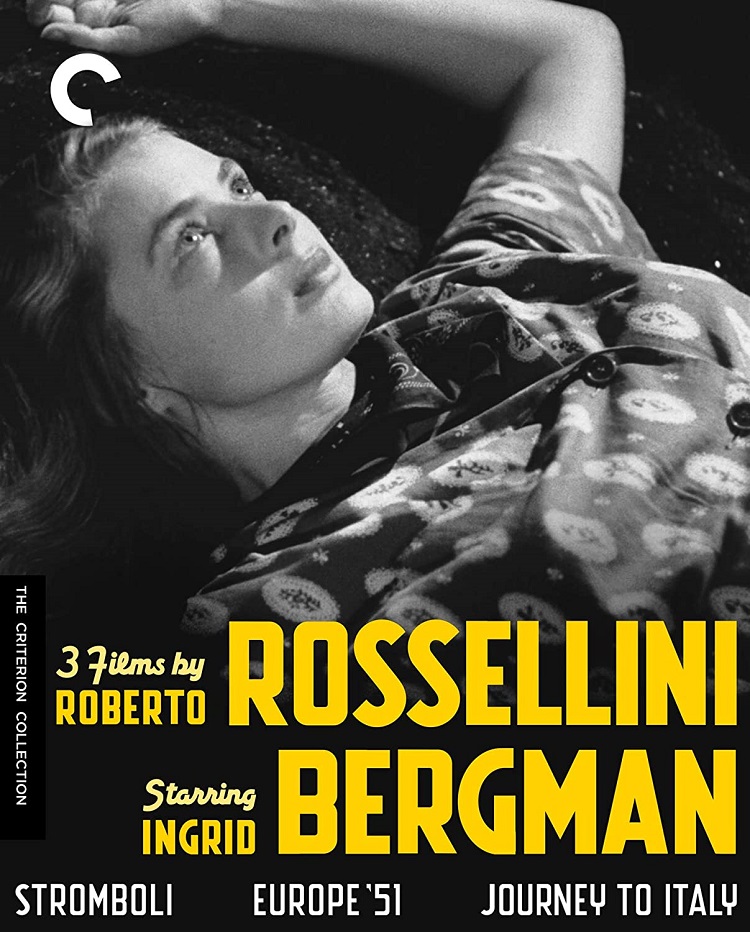

Though their collaborations were largely overshadowed by the scandal of their romance, Roberto Rossellini and Ingrid Bergman proved to be fruitful cinematic partners as well, their films together pushing Rossellini into new stylistic territory and giving Bergman some of her most fully realized roles.

In the three features included in the latest invaluable Criterion box set, Rossellini is consciously moving away from the neorealism of films like Rome Open City and Paisan (the very films that inspired Bergman to reach out to him, and available in another superb box from Criterion) to a more individually focused, more emotionally internal brand of cinema. Melodrama is still one of Rossellini’s tools here, particularly in the two earlier films, but with the immensely expressive performances of Bergman to depend on, he draws devastating portraits of isolation and despair.

The set’s first film, Stromboli (1950), stars Bergman as Karin, a Lithuanian refugee trapped in an internment camp in the wake of WWII. When an opportunity presents itself in the person of Italian POW Antonio (Mario Vitale), she takes it, marrying the near stranger and accompanying him back to his titular home island. Freedom is hardly what awaits her there; the desolate, harsh living conditions and the stern demeanor of the residents of Stromboli put Karin in an emotional prison of her own making. A flirtation with a strapping young lighthouse attendant (Mario Sponzo) and conversations with a sympathetic priest (Renzo Cesana) provide some temporary respite but not much.

The vestiges of neorealism are still here, as Rosselini’s camera can’t help but be fascinated by the real residents of Stromboli and their local customs, including a physically demanding fishing regimen and evacuation procedures when the nearby volcano erupts. Still, he uses these segments in service of further examining the emotional turmoil of Karin, with the volcano itself finally providing the catharsis she longs for, although Rossellini refrains from revealing whether it’s a negative or positive development.

Next up is Europe ’51 (1952), the most overtly melodramatic of the set, and perhaps the easiest to dismiss because of it. But while the film paints in broad emotional strokes, it also possesses a potent political and spiritual power. Yes, it’s a little less formally interesting than the other two films, but Bergman is fantastic as Irene Girard, a woman insulated by her and her husband’s (Alexander Knox) wealth in hurting post-war Rome.

The film’s aloof political conversations among high-class socialites are interrupted by the death of the couple’s troubled adolescent son, Michel (Sandro Franchina), and the experience shakes Irene to the core. Encouraged by her Communist friend Andrea (Ettore Giannini) to sublimate her grief by helping the less fortunate, she throws herself headlong into charity work, donating money to fund hospital bills, caring for the severely ill and even filling in on the line at a factory so a harried mother (Giulietta Masina) doesn’t lose her job.

Irene’s husband can’t understand her sudden absence, and he and his social circle assume she’s having an affair, and later, worse. Rossellini desired to make a film about the social and political implications of a modern-day Francis of Assisi, and he succeeds in the macro — portraying a deeply divided society, largely unwilling to acknowledge the divide — and the micro — examining the fraught emotional state of a woman so unwilling to forgive herself, she has no choice but to abandon herself to the needs of others.

The set closes with the most lauded and the most revolutionary film of the three, 1954’s Journey to Italy, a film François Truffaut called the “first modern film.” Bergman stars as Katherine Joyce, a woman who travels with her husband, Alex (George Sanders), to Naples so he can deal with the estate affairs of his late uncle. Early on, the couple admits they’ve drifted apart, and soon the indifference turns nearly to outright animosity. The vacation is spent largely apart from one another; he attempts to woo a pretty young thing in Capri while she walks among the museums and ruins in Naples. There’s talk of seeing an old flame, but he never materializes; all Katherine is left with are irascible old men taking her on tours and the unmoving, unfeeling faces of statues.

Journey to Italy is a remarkable study of futility. Bergman is superb at portraying the gnawing loneliness and the desire for something, anything to shake up her wounded, yet complacent emotional state. One expects a handsome potential lover around every museum corner, but there’s never anyone there. Here, Rossellini moves away from plot and dampens the cursory melodramatic aspects of his story. He intertwines images of love and death, of perfunctory ceremony and yes, some passion, but how authentic? Is the ending a copout or the acknowledgement that solitude is far worse than a loveless existence, drained of feeling? Journey to Italy helped kick off an era of cinema far more interested in asking questions than providing answers.

The Blu-ray Discs

All three films are presented in 1080p high definition and 1.37:1 aspect ratios on their own discs. Alternate Italian-language cuts of Stromboli and Europe ’51 are presented alongside the English-language versions. Stromboli features a strong transfer occasionally hindered by some invasive damage to the elements; fortunately, the majority of the film looks crisp and clean. Europe ’51 possesses the weakest transfer, with a fair amount of heavy damage (some nasty vertical lines), print fading and contrast issues popping up intermittently. The digital transfer is still good, preserving the film-like quality of the image and presenting some moments of excellent clarity when the materials allow for it. Journey to Italy is downright gorgeous, far less plagued by damage than the other two films. Images are sharp, grayscale separation is immaculate and the transfer is very stable.

The uncompressed mono soundtracks are at the mercy of the elements, but mostly everything is in good condition, allowing for intelligible dialogue even when it sounds rather hollow.

Special Features

There’s a treasure trove of extras here, with supplements spread across the discs of the three films and a separate fourth disc. Archival introductions from Rossellini are included alongside each film, as are new interviews with the extremely knowledgeable Italian film critic Adriano Aprà. Disc one also features a 1998 documentary that returned to the island of Stromboli 50 years later. Disc two contains an extensive interview with historian Elena Dagrada as she explains the differences between different versions of the films. Disc three enlists the great Tag Gallagher for an indispensable visual essay on Rossellini’s evolving style and the equally brilliant James Quandt for a visual essay on the trilogy’s historical themes. Interviews with Rossellini mega-fan Martin Scorsese and daughters Isabella and Ingrid Rossellini are also included, as is behind-the-scenes footage from the production of Journey to Italy and an audio commentary by scholar Laura Mulvey.

Disc four features a 1992 documentary on Rossellini’s career, a 1995 documentary on Bergman’s career, Bergman’s home movies, an interview with Rossellini’s niece G. Fiorella Mariani and two short films — 1952’s The Chicken, starring Bergman and directed by Rossellini, and 2005’s My Dad is 100 Years Old, starring Isabella Rossellini and directed by Guy Maddin.

The set also includes an 85-page booklet with essays, interviews and letters between Bergman and Rossellini.

The Bottom Line

A monumental release of Italian cinema and one of film’s greatest partnerships, Criterion’s newest box set is yet another essential.