Long before the term “direct-to-video” was even so much as a twinkle in a greedy movie exec’s eye, the idea of making a sequel to a science fiction film was as propitious to a motion picture studio as was Orson Welles trotting off to his favorite all-you-can-buffet one day with a 50%-off coupon, only to encounter a “Closed For Good!” sign hanging on the door. The reason for this was simple: film studios shied away from the manufacturing of sci-fi flicks in-general, believing them to be for losers, nerds, geeks, dorks, and people that would come to be known as “basement-dwelling-fanboy-trolls.” Worse still, when those godlike moving picture gurus were actually willing to take the plunge to produce a science fiction movie sequel, they usually wound up with something like Forbidden Planet’s “follow-up” film, The Invisible Boy — a film so vastly removed from its source material that even referring to it as a sequel will often encourage the angst of said “basement-dwelling-fanboy-trolls.”

Indeed, the very genre of science fiction itself was a back-burner affair; something that was generally assigned to a company’s prestigious “B” unit. That all changed, however, when Planet Of The Apes came out in 1968. The film’s monstrous success prompted Twentieth Century Fox chief Richard Zanuck to rush a movie into production that would pick up after the events depicted in the previous feature. Unfortunately, Charlton Heston wasn’t too keen on reprising his role as unlucky Taylor, the cynical and ill-starred astronaut who crash-landed on a “planet where apes evolved from men,” and only agreed to make an appearance that would basically amount to little more than a cameo.

This, of course, presented a problem. Would Fox be able to pull off another film without its star power? Budgetary limitations resulted in several proposed scripts for the film (ranging from the minds of Rod Serling, the first film’s screenwriter; to Pierre Boulle, the French author whose work the original movie was based off of) being rejected, leading the project into the lap of British writer Paul Dehn (who was able to pen a story that fit Fox’s low financial plan). This brought about another predicament: would they be able to match that truly epic ending (to say nothing of the other innovative elements) that the original Planet Of The Apes forever changed the film industry with? Well, that’s a subject that a lot of people — from those basement-dwelling-fanboy-trolls to fully-functioning members of the human race alike — like to get into oft-heated furors over.

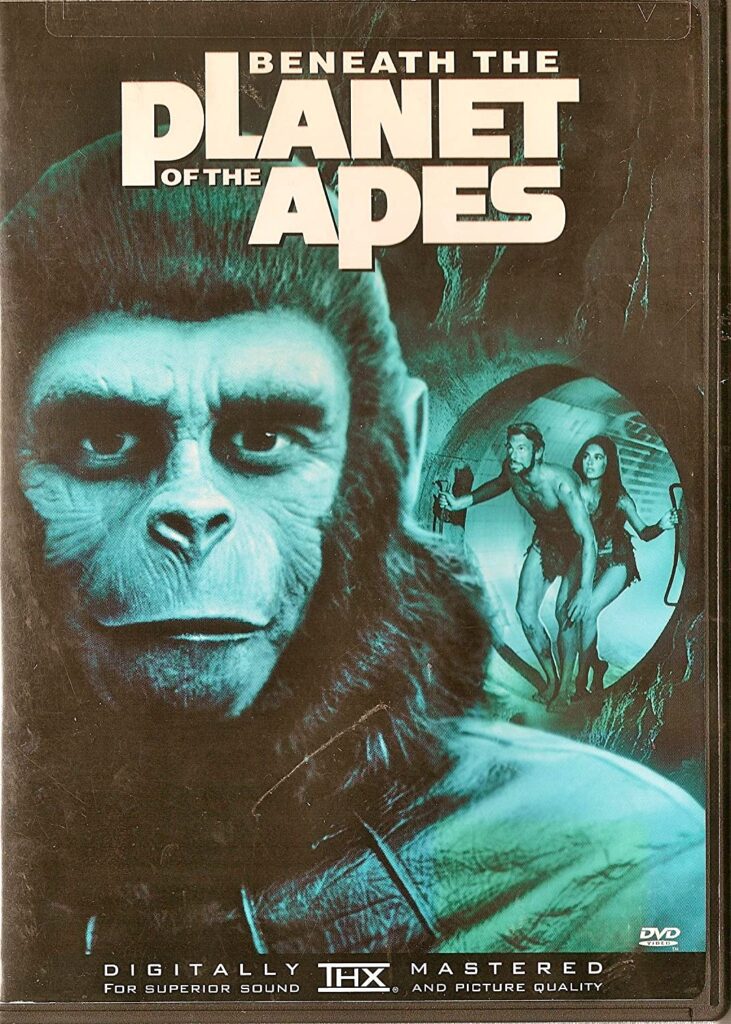

I, for one, positively adore 1970’s Beneath The Planet Of The Apes. In fact, it is one of my favorite films in the entire (original) Planet Of The Apes legacy — and my unabashed esteem for the movie often causes some people to question my very sanity (I’m also strongly enthusiastic about Conquest Of The Planet of The Apes, the collective works of library music by Keith Mansfield, and I think Timothy Dalton was an extremely underrated James Bond if that tells you anything). Now, here’s the kicker: I fully realize that Beneath The Planet Of The Apes is a bad movie. I’m completely coherent it’s nothing more than a hurried B-movie sequel to an unexpected B-movie hit (which probably puts in closer into the prestigious “C-Movie” category, truth be told).

But that’s just one of the reasons it’s so great.

We begin with a recap to the first movie’s ending, wherein our human protagonist Taylor (Charlton Heston) rides off into the Forbidden Zone, only to find some truly bad news about the mysterious planet he crash-landed on (they didn’t have home video back then that would allow audiences to re-watch the former film, so a recap of the ending more than suffices). We then meet the film’s real star, the great James Franciscus (whose similar features to Heston’s earned him the role) as astronaut Brent — the only surviving member of another doomed space expedition that crash-lands on the planet (this time in the desert); this mission launched to discover what happened to Taylor and his crew. It’s a recycled formula, for sure: the only major difference is that Brent’s only other crew mate, his skipper (known simply as “Skipper”), dies from injuries sustained in the crash. While we can’t be sure, it’s likely that the demise of the “Skipper” is attributable to the fact that the guy couldn’t grow a beard while in hibernation like everyone else did. That, or Brent just flat out killed him — which some might suspect, given the film’s somewhat bizarre editing there.

But, unlike Taylor, Brent only has a limited amount of screen time to go through the whole shock-and-awe-show that his comrade did: in the first thirty minutes or so, he meets Taylor’s mute mate Nova (once again played by Linda Harrison, who was Richard Zanuck’s honey at the time), discovers Taylor is missing, discovers the planet is ruled by monkeys (“My God, it’s a city of apes!” the actor croons), gets captured by the militaristic gorillas of Ape City, and is freed by chimpanzee doctors Zira (Kim Hunter, returning to repeat her performance) and Cornelius. The latter ape is not played this time by Roddy McDowall, though — instead being portrayed by the decidedly nowhere-near-as-great-as-Roddy-McDowall actor, David Watson (McDowall was off directing a movie in England and was unable to revive his part).

And thus, several important B-Movie Rules are honored. We quickly establish a new main lead — who is really nothing more than a redux of another character — without so much as a whim to focus on the universe the story is set in (it had already been created in the last film, after all), and then goes on with its next chapter assuming we’re all on the same page and rarin’ to go (and tough titty if you aren’t). It removes another actor from the equation (Roddy McDowall) and replaces him with someone else: something the ‘bots from Mystery Science Theater 3000 once dubbed “Wayne Rogers Syndrome” (a theory that suggests producers always call on Wayne Rogers when a previous actor cannot be negotiated into returning to a role). And, after all that, it washes away most of the old cast to concentrate on the new guy.

Soon, Brent finds himself Beneath The Planet Of The Apes, in what was once New York City (as well as its former subway system — both of which have been squished together and moved onto one single level). But he is not alone. Sure, Nova’s there with him, but she’s about as talkative as an elderly white politician who finds himself in an all-black neighborhood. No, much to the surprise of Brent and the audience, too, we find that the old human race that helped bring about the initial “Rise Of The Planet Of The Apes” is not extinct after all. In fact, the remains of NYC are now inhabited by a race of telepathic mutants — led by the “Méndez” (Paul Richards) — who are not only able to control running water with their mind, but are able to inflict horrifying visions upon those who they deem to be enemies. And everyone is an enemy in their eyes.

They also worship an unexploded atomic bomb.

Yes, you read that right.

And therein is one of the movie’s greatest saving graces: The Church of Méndez. If James Franciscus’ self-conscious soliloquizing throughout the buried ruins of New York wasn’t enough to bring a grin to the face of even the most jaded B-Movie enthusiast (remember: them mutants mostly communicate telepathically, whereas Nova can’t communicate at all), the sight of an entire congregation of mutated humans worshipping a weapon of mass destruction — or should I say the weapon of mass destruction, as this Alpha-Omega bomb is designed to damn everyone as well as everything to hell — should. Screenwriter Paul Dehn, who was particularly traumatized from the Bombing of Hiroshima and more than just a little obsessed over the subject of nuclear abomination and its subsequent aftermath, takes the religious commentary from the first film and cranks it up to “11” here. Classic.

Meanwhile, a shrewdness of apes (many of whom are donned in painfully-blatant generic ape masks) march into the once-outlawed Forbidden Zone so that the audience can be reminded that this is still a sequel to Planet Of The Apes. The army of gorillas, under the command of the warring General Ursus (James Gregory, giving one of the most lively and scene-stealing performances of his vastly underestimated career) and orangutan Dr. Zaius (Maurice Evans, back to delight those of us who tend to laugh at the way he pronounces the letter “b” — it’s much like Droopy’s unique method of enunciation in my opinion). The impending war with the as-yet-unknown adversary is unappreciated back in Ape City by the pacifistic chimps (whose protests reflect the anti-Vietnam War demonstrations of the time), but, as General Ursus reminds the entire simian culture: they either fight, or starve due to a diminished food supply.

Hey, it sure beats going into a prolonged battle over oil, doesn’t it? Now, if only the apes had marched for a little longer, they could have waltzed right onto the set of Soylent Green and had all kinds of food! And since I’ve mentioned both he and food thus far, now is as good of a time to mention Orson Welles was asked to play Ursus, but refused since he’d have to wear a mask.

Alas, the Ape/Mutant War of 3955 doesn’t last very long. It isn’t long after the two long-removed cultures encounter one another that they clash like Boy George’s sense of fashion during the peak of his heroin days, to wit, the words of Morrissey come to mind: “If it’s not love, than it’s the bomb, the bomb, the bomb, the bomb, the bomb, the bomb, the bomb that will bring us together.” Granted, we’re privy to the larger-than-life one-on-one combative conflict between Charlton Heston and James Franciscus to see who is the true human hero of the series beforehand at the behest of the telekinetic mutants (“Mr. Taylor, Mr. Brent, we are a peaceful people — we don’t kill our enemies, we get our enemies to kill each other”).

In perhaps the film’s most incongruous twist of fate, Linda Harrison’s mute Nova finally figures out how to articulate an earnest attempt at a syllable shortly before she is forced to bid the world “adieu” by a rampaging gorilla (Harrison would return for a cameo in Tim Burton’s awful 2001 “re-imagining” of Planet Of The Apes, along with Heston — who has that rare cinematic distinction of having both saved worshipers onscreen as well as wasting them thanks to this movie). And there we have another reason I love Beneath The Planet Of The Apes so much: its demented sense of irony.

Further factors of my near-Méndez-like sense worship for the film include the delightfully subdued delivery of James Franciscus — an exhibition that borders on manic, and that suggests Brent may actually be a complete psychopath; the fact that director Ted Post and screenwriter Paul Dehn not only seemed to enjoy creating this twisted chapter in the saga, but did they best they could with what Fox gave ’em; and a number of performances that are generally disregarded by actors such as Thomas Gomez, Jeff Corey, Natalie Trundy (wife of Apes producer, Arthur P. Jacobs), Gregory Sierra, Victor Buono, and Don Pedro Colley — whose character was named “Ono Goro” in the script, but who is inexplicably credited as “Negro” in the closing credits!

Like I said before, I’m fully aware that Beneath The Planet Of The Apes isn’t the award-winning masterpiece that its precursor was. But its low-budget charms manage to sway me each and every time I view it. Heck, for my money, there aren’t a whole hell of a lot of movies that can top the outcome of Beneath The Planet Of The Apes. Some say “nay” to the film’s final destructive moments — wherein we witness the end of everything ever — but I cherish its strange sense of B-Movie extremism: a subtle sagacity that gets too wrapped up in trying to one-up its predecessor, only to ultimately (and unintentionally) succeed in creating something so incredibly sublime. Plus, there’s another B-Movie point to be had (even after Charlton Heston gets to “burn the planet to a cinder”) that of an aural cameo by veteran voice actor Paul Frees, whose marvelous tenor carries on into the far reaches of space like the voice of God itself — inform the film’s otherwise floored viewers that all is indeed lost.

Although ye should, fear not, kiddies: all was not long for too terribly long. Much like the first nuclear apocalypse brought about new life, the second atomic holocaust brought about a new legend — one that only the collective genii of producer Arthur P. Jacobs, writer Paul Dehn, and actors Roddy McDowall and Kim Hunter could bring to the screen.

But that’s another story entirely. Well, three stories, really.