The Second World War is a different story, depending where it’s told. For Americans, it can be complex (how our country, isolated from much of the world, was finally, inextricably enmeshed in the political troubles of the entire globe) or simplistic (America flew in and rescued everyone, kickin’ Nazi ass!) and it can fit anybody’s political world view as long as the right facts are emphasized and complexities are smoothed over.

For Britain, it was something different. England had been involved in continental wars for all of its history, but those conflicts never made it across the channel. In World War II, Britain had the hell bombed out of them and there was a very real chance that the Axis powers, once they had control of the western coast of Europe, might be sending ships across that small channel and invading England’s shores.

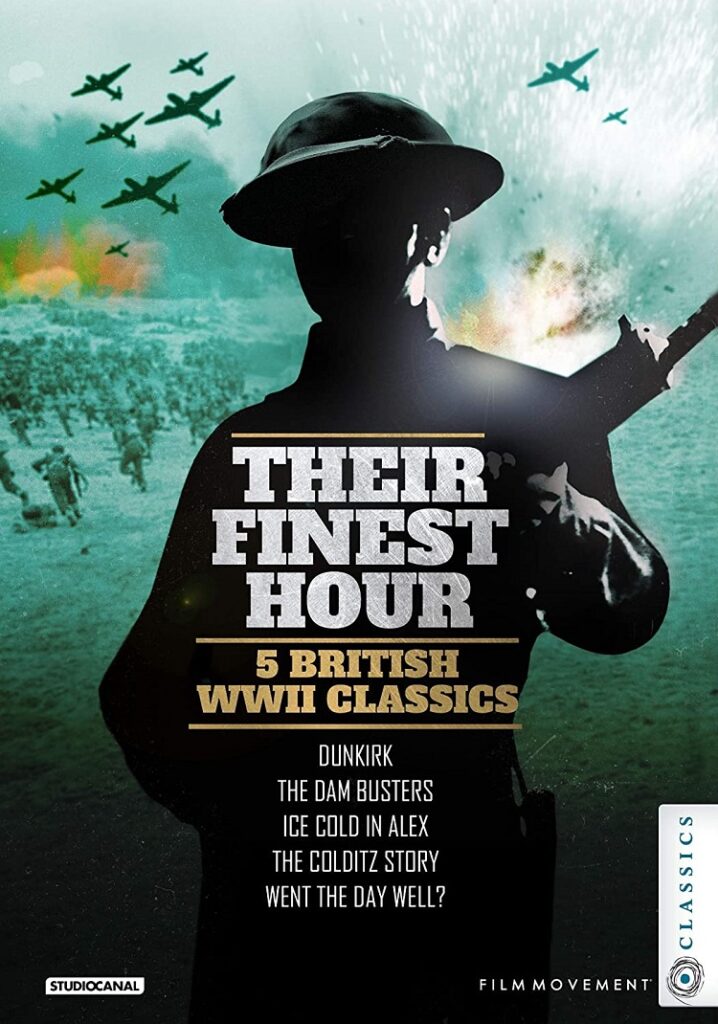

In five films, Their Finest Hour: 5 British WWII Classics illuminates both the state of mind of war-time Britain, and how attitudes toward the war, and war in general changed as time drew distant from the conflict. One film was made during the war, the rest several years to more than a decade after, and they demonstrate both the resolve of the British soldiery and populace in the face of adversity, and a growing skepticism toward the entire endeavor of military conflict, and the easy lines of black and white, good guy/bad guy thinking war requires, and fosters.

Taken in chronological order:

Went the Day Well (1942) is the only film in this set that was made while the war was still being waged. Based on a Graham Greene short story, it is a slightly fantastical thriller about a clandestine infiltration of Germans into a small British town. It begins with a jolly narrator taking us to a headstone in the local cemetery, the only one with a set of German names on it. How did those Germans find their final rest in a little British cemetery? Well, they made the mistake of setting foot on God’s own soil during WWII, that’s how.

Went the Day Well begins as a British comedy of manners – a crew of Army engineers comes into town, and the different factions in town all begin to jockey for the right and honor to billet the officers in their homes. Hint, Brits: this is why we have the third amendment here in the states. It couldn’t have happened here. Anyway, while everyone is being small-town cute, the infiltrating Germans (along with a traitor who has been in town for years) begin to slowly cut the town off. It will the landing zone where the rest of the evil Huns will sift onto British soil and conquer the country from within.

Eventually, the plot is uncovered, and the Brits and the Germans go into open warfare, where the mettle of the average slovenly British citizen is tested. This is a wartime film, so of course, that mettle is found to be beyond measure. It’s a fun little thriller, all about the certainty that, when push comes to shove, the little Britains will have what it takes to throw out their barbaric invaders.

Went the Day Well was purely fictional, but the rest of the films in this box were at least nominally based on historical events. The least likely of these real tales is The Colditz Story (1948), which might be best described as a British cinematic forerunner of Hogan’s Heroes. Colditz was a castle in Leipzig, used as a prison camp for Allied soldiers who had escaped from other prison camps. Because Colditz was a historical prison, it was considered by the Germans to be inescapable and so the only pastime for the prisoners was to find different ways to prove that it was, indeed, extremely escapable.

We see the prison through British eyes, particularly Pat Reid (John Mills) and his mate, who are the first British prisoners inside a castle already filled with Poles, Dutch, and French. John Mills was a British actor who rather specialized in playing soldier types – he’s the lead actor in three of the films in this collection. Here, he’s an army officer who, from the moment he comes to Colditz begins to plan his and his men’s escape.

The problem is all of the other prisoners are also planning their own escape, and they fall over each other’s feet constantly. First it’s a Frenchman on the roof, sending down roof tiles, alerting the guards when the Brits are trying to pry open a sewer grate. Then a long tunnel the British are digging gets caved in by the enormous Dutchmen who are digging their own tunnel just a few feet above them.

It takes a British officer, Colonel Richmond, to organize the various nationalities into a concerted escaping force. The different groups plan their own escapes, and make sure that nothing they do interferes with any of the other escape plans.

For the Germans, the constant attempts to break out of their prison seems to be a nice break from the routine of policing prisoner. When Colonel Richmond first comes to the camp, the Commandant tells him in no uncertain terms that any attempt to escape will result in immediate execution. But it becomes clear the Commandant doesn’t mean it, since the worst that happens to anyone is solitary confinement, and the word “solitary” is meant pretty loosely, since they’re always in “solitary” with other people. The only real baddy is the local member of the Gestapo, whom the other Germans seem to despise as much as the prisoners do.

The Colditz Story is based on a real account by Pat Reid about his experiences in the prison castle, which did have an amazing amount of escape attempts, and successes. The tone of the film is jaunty, almost like an adventure story rather than a POW story. It’s a fun film, if a trifle silly. The real life stakes of escaping the prison might have been sky high, it all seems like a game in this film.

The Dam Busters (1955) might be the most famous film in this collection, if just for the Dam Busting sequences which formed the basis for the Death Star trench attacks in Star Wars (1977). George Lucas obsessively examined the footage from this movie to create his own intense space action, and that’s fitting since this film is partly about obsession. Barnes Willis, an inventor and aircraft designer, has an inspiration: he wants to destroy a set of dams that are integral to steel production for the Third Reich, and he has come up with a novel design for a bomb that he thinks, with a very specialized attack plan, might be able to work. The bomb is the bouncing Betty, a five-ton explosive that will only go off at a certain depth, and that can be launched from a plane several hundred yards from its target, and bounce off the water until it hits the dam, and sinks to the appropriate level.

The Dam Busters is structured in basically three parts – the invention of the device, the collection and training of the flymen who can pull off the mission, and the eventual mission itself. Barnes Willis is the initial main character, who has to fight layers of bureaucracy and military inertia to get any support and funding for his project. Once it looks likely to succeed, Guy Gibson, the selected squadron master, becomes the secondary protagonist, who has to train his men to very specific, very dangerous mission specifications without knowing until the last minute just what the hell he’s training for.

More than 10 years after the end of the war, The Dam Busters does not have as much of a ra-ra, sort of jingoistic view of the brave men fighting bravely with their stiff upper lips at the front line. Much of the movie is given to training, to uncertainty, to failure and disappointment as the preparation for a difficult task begins to look like a waste of valuable resources and time. It’s also a more naturalistic film than the two proceeding – these warfighters and heroes spend a lot of their time sitting around, drinking, and not being sure of themselves, even after their mission is done.

The Dam Busters contains some incredibly tense action sequences. Many of the special effects fall apart with modern scrutiny, but some still hold up, and there are some incredible real flying sequences that help to lead to some nail-biting cinema. It’s not for nothing that Lucas cribbed the trench sequence from this film

Dunkirk (1958) has many just as tense sequences, and is even more ambivalent about the stiff-upper lip narrative of British warfighting. This piece of history, made recently famous by both the Christopher Nolan film of the same name and the climactic sequences of the Churchill biopic Darkest Hour, has a newly familiar narrative: the British army is stuck in western Europe as the Germans come to surround them, and push them towards the sea. There aren’t enough Navy boats to evacuate all of the soldiers, so civilians on the British coast are recruited to cross the channel and bring as many boys home as possible.

Dunkirk opens and closes with documentary footage, making sure the reality of the situation is clear to the viewers. But the story of the film bounces between two main, fictionalized groups – a pair of civilian boat owners in England, and a small squad of troops who’ve lost their company and just want to get somewhere where somebody can start giving them some orders.

The civilians are two orders of society – the journalist Foreman, who knows what the country should be doing and is infuriated that no one is doing it, and the machine shop owner Holden (played by Richard Attenborough, who made a career of playing meek and nervous British men before he became an acclaimed director) who is happy with his war profits, but doesn’t really want to help out the war himself. They’re both boat owners, and serve as two different civilian observers: the disappointed realist vs the capitalist opportunist.

The squad are reluctant followers of their corporal (John Mills, whom we remember from The Colditz Story) who don’t believe anything they hear from command, even when they hear nothing from command. They’re told to head to the beaches, where they will be evacuated. But when they reach those beaches, they see men creating make-shift piers to get close to the boats, which are getting bombed out the moment they set off from short.

Dunkirk is more of a frontline movie than the previous three, about soldiers far from command who don’t trust anything they’re told, who move from space to space expecting to be shot out from whatever desperate position they take. It’s a harrowing story of attrition, as every place they go the random combat takes one or two soldiers.

This is where the narrative of the stiff upper lips begins to be questioned, though it isn’t wholly undermined: the civilians who have to give up their ships begin with trepidation, but when the navy begins to pull out and abandon the men the normal citizens of Britain fill in the gap, and try to rescue the soldiers right on the beaches.

Ice Cold in Alex (1958), set in North Africa where the British attempted to keep the Axis from invading Europe from the south, is a more desolate tale. Again starring John Mills, with bleached blonde hair as a corporal who has reached his psychological limit, he’s tasked with driving an ambulance truck from Tobruk in Libya to Alexandria. Encumbered with a couple of nurses who had hidden out during a bombing raid instead of escaping with their fellows, and without the whiskey that makes his life worthwhile, Mills is not the stoic British officer seen in previous films. He’s neurotic, shaky, and he makes clear mistakes.

The title of the film refers to Mills’ goal: he’s ready, after a terrible mistake, to lay off the drink until he reaches Alexandria, where he’ll get an ice cold lager. He takes off on the trip with his sergeant major, and two nurses: one is a stalwart sort of gal, the other who can’t take the stress of bombings and random chaos. On the way, they pick up an Afrikaans who speaks German. The whole troupe needs to make it across the desert.

The closest comparison I can make to Ice Cold in Alex is the classic film Wages of Fear – which, after about an hour of character development, has 90 minutes of the tensest action ever filmed, with a truck filled with explosive nitroglycerin trying to make it through narrow, difficult tracks. Ice Cold in Alex isn’t as tense (no film, perhaps, has ever been) but it highlights the sheer physical difficulty of the trek across the desert. There’s a long sequence of slowly trudging the ambulance through a minefield, a disaster in quicksand, and multiple encounters with German patrols that nearly end in disaster.

All of these films are presented in their original beautiful black and white, and with mono soundtracks. Thematically, they form the bridge from British confidence in the face of war to a more skeptical view of heroics. But, despite some of these films’ pessimistic aspect, the real central theme is perseverance. The strength of humanity against adversity. Dunkirk and The Dam Busters are the most special effects laden, and they of course suffer from being made nearly 70 years ago – but the filmmaking, taken on its own terms, is tense and engaging. Some of the action in these films is serious seat-of-the-pants thrilling. The Dam Busters (which Peter Jackson has been endeavoring to remake for more than a decade) is the obvious standout, but Ice Cold in Alex deserves a new modern audience with its tense performances, and outstanding action sequences. This collection of films is not a series, and little connects them except for their Britishness (and John Mills starring in three of them) but it’s a worthwhile collection, all the same. This is how, to some degree, the war looked to the people who endured it, during and after.

Their Finest Hour: 5 British WWII Classics has been released on Blu-ray by Film Movement Classics. Each film is on its own disc, and each disc has its own set of extras, except for Went the Day Well. The Colditz Story has a video documentary about the prison and its attempted escapes, “Colditz Revealed” (54 min), and a short demonstration on the film restoration (3 min). The Dam Busters has the most extensive extras on disc, a documentary on “The Making of Dam Busters” (40 min), a doc on the inventor Barney Willis (29 min), another documentary about the 617 squadron (57 min), and smaller video extras, including Footage of the Bomb Test (7 min), the Royal premiere of the movie (3 min), and a short doc on the film’s Restoration (5 min). Dunkirk has a short newsreel doc about the movie (4 min), an interview with actor Sean Barret (23 min), a short film Young Veteran (23 min), and a collection of films that actor John Mills shot on set (10 min). Ice Cold in Alex has an excerpt from the documentary “A Very British War Movie” (13 min), more John Mills home movies (15 min), an interview with film historian Melanie Williams (16 min), an interview with Steve Chibnall about the film’s director John Thompson (13 min), and a highly delightful interview with actress Sylvia Syms (22 min). The accompanying booklet contains an essay about all five films written by Cullen Gallagher.