Director Akira Kurosawa (1919-1998) was known as “The Emperor” of Japanese film for a few reasons. For those he worked with it was because his word absolute law both on and off the set. In another time, anyone disagreeing with him may have been subject to an “off with their head” response. For his fans around the world, The Emperor was an acknowledgement that he was the undisputed master of his craft. Kurosawa made a total of 30 films in his lifetime, and several are rightfully considered masterpieces.

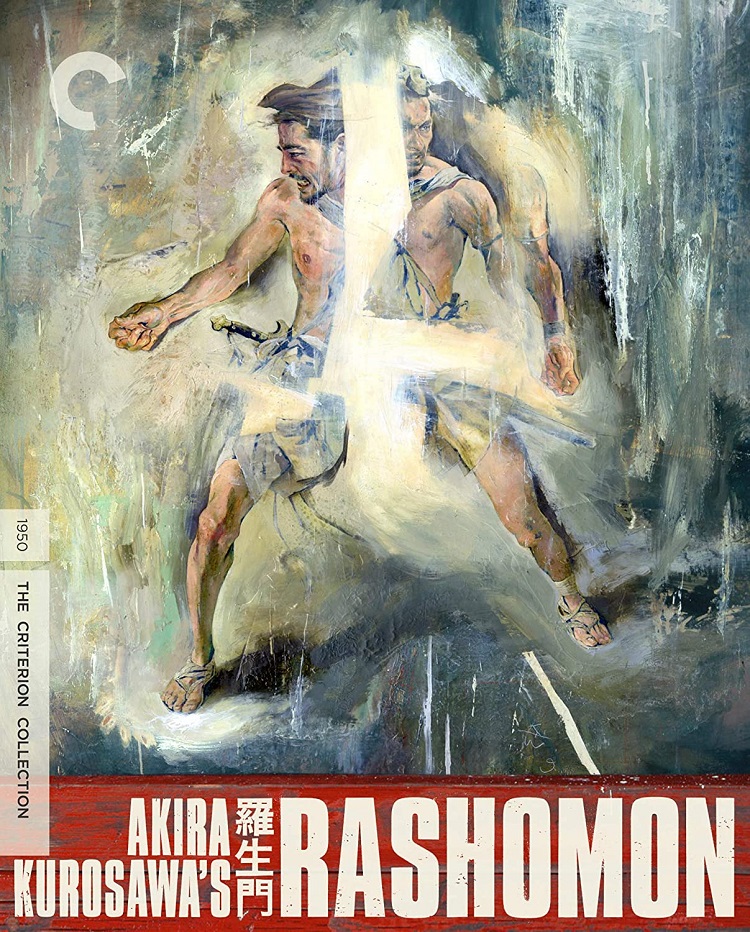

To pick the greatest of Kurosawa’s movies is a highly subjective, and probably a futile proposition. Nevertheless, after watching the newly released Criterion Collection edition of Rashomon, I have come to the conclusion that it is my choice as the best of the best. The digital remaster of the film actually took place back in 2008, under the auspices of The Academy Film Archive, The National Film Center of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, and Kadokawa Pictures, Inc. It was released then by Criterion with no extras, so I am thinking that this release has been issued as “new” because it contains quite a number of bonus features.

Rashomon is visually stunning. When I first saw this film, it was a VHS tape, and the picture quality was average at best. This restored version is magnificent, and probably as close to what it looked like on the big screen 62 years ago as is possible. With the right use of shadows and light, there is an art to filming in black and white that can be even more impressive than color. To achieve this, there has to be an excellent rapport between director and cinematographer. Orson Welles and Gregg Toland certainly mastered the form with Citizen Kane (1941). It appears that Kurosawa and his cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa shared a similar point of view.

For the current generation of film-goers, Rashomon has two strikes against it though. One is that it is in black and white, and the other is the fact that the dialogue is Japanese, with English subtitles. Consequently, the audience for such a picture is pretty small, which is unfortunate. There is hope I suppose, considering that The Artist (2011) won the Academy Award for Best Picture last year, but that was definitely an anomaly.

My point is that I wish more people would accept the hurdles involved in watching Rashomon, because it is a truly great film. The most talked about element of Rashomon is the groundbreaking format of the plot. Kurosawa wrote the screenplay, based on “In The Grove” by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa. The phenomenon the film depicts has now become a psychological term, “the rashomon effect.” What this phrase describes is the tendency of people, (probably dating back to the beginning of time), in which eyewitnesses to an incident will report vastly different accounts of it. I have even seen experiments about this strange phenomenon, with people hooked up to lie-detector equipment, relating incredibly differing accounts of the same event, and both passing with flying colors. In 1950, Rashomon inadvertently gave this odd characteristic a name.

In the movie, the variations on the story are relayed by four individuals. They are a woodcutter (Takashi Shimura), a notorious bandit (Toshirô Mifune), a murdered samurai (Masayuki Mori) whose version is bizarrely told by a disturbing female medium (Noriko Honma), and the samurai’s wife (Machiko Kyō).

While taking cover from a torrential downpour under the decaying Rashomon bridge, the woodcutter and priest are approached by a commoner (Kichijirô Ueda). The two relay the troubling story of the rape of a samurai’s wife, then the murder of the samurai. Both have different versions of the tale, with the woodcutter saying that he discovered the samurai’s body three days earlier, while the priest says that he had seen the samurai and woman riding together that very day.

Both are summoned to court, where they meet the bandit Tajômaru, who proudly brags that he tied up the samurai, and “took” his woman in front of him. Not only that, but she evidently liked it so much that she directed Tajômaru to kill her husband. Things get even stranger when the medium tells the story from the samurai’s point of view. He says he was tied up, his wife was raped, and again “liked” it. She cut her husband loose, and directed the two to fight to the death to win her. The samurai was so disgusted that he killed himself. Watching Rashomon 62 years later, one of the more striking points is that the blame falls on the woman in these versions of the samurai‘s death.

In relating the basics of the story, I have intentionally left out an event that comes in the final five minutes of the movie, and adds a whole new layer of possibility, and depth. It is so unexpected, and so strange that I do not wish to spoil it here. The film has been out since 1950, so if you want to know this final scene without actually watching the movie, I am certain you could find it somewhere. But I’m not going to give it away.

After watching the film in the regular way, I decided try a little experiment for this review. Since all of the dialogue is sub-titled (and this was my fourth viewing), I turned off the sound and watched it as a silent movie. This removed all of the auditory distractions, and I was able to completely focus on the visual presentation. It was kind of an amazing experience because I finally began to comprehend the film language of Kurosawa.

Watching Rashomon without the sound was almost like seeing a completely different movie. His use of sparse locales, the framing of the actors, the intense rain at the Rashomon gate contrasted with the clear, almost serene atmosphere at the outdoor court, and the long focus on certain objects all took on a much deeper significance.

I also believe that I at least began to understand the whole John Ford connection. Kurosawa employed a visual style that had a great deal in common with that of Ford. Obviously the settings and stories of Rashomon and Ford’s My Darling Clementine (1946) are very different, but the imagery is strikingly similar. It was something of an epiphany for me, like discovering a form of poetry I was never really aware of before.

I hope these personal musings are not too self-indulgent. The late Robert Altman is one man whose thoughts on film definitely are welcome though. In one of the extras, he talks about how Rashomon affected him: “In this film, one takes something as truth, then you find out that it is not necessarily true. You see various versions of this episode that has taken place, and you are never told which is true and which isn’t true. This leads you to the proper conclusion that all of it is true, and none of it is true. It certainly changed my perception of what is possible, and what is desirable in film. You have to let the audience come to their own conclusion.”

That is just the beginning of the extras though. Next up is a 12-minute excerpt from The World of Kazuo Miyagawa, a Japanese documentary about Kurosawa’s Rashomon cinematographer. A Testimony as an Image (68 min) is the most substantial of the bonus features, and focuses on script supervisor Teruyo Nogami. Also included in this discussion of the film, and of Kurosawa in general, are Rashomon co-writer Shinobu Hashimot and assistant director Tokuso Tanaka. The final piece is an audio interview with actor Takashi Shimura, the woodcutter in Rashomon. The interview took place at the 1961 Berlin Film festival, and was conducted by Gideon Bachmann for his radio program The Film Art, and is translated into English, which makes for interesting listening. I found his careful responses to questions about the director’s reputation as “emperor” on the set and how he elicits the best performances from his actors quite intriguing.

The legacy Altman spoke of about Rashomon letting the audience come to their own conclusion is one of the film’s lasting legacies, and there are many others. For those who have never seen it, by all means, please do. And even if you have seen it, I say see it again, because this digital remaster is very impressive, as are the bonus features.