Written by Lisa McKay

The tragedies and controversy swirling around director Roman Polanski’s personal life have frequently overshadowed his reputation as a filmmaker, especially in the U.S. Nonetheless, his body of work stands on its own merits and he remains one of the shining stars of the cinematic landscape of the ’60s and ’70s.

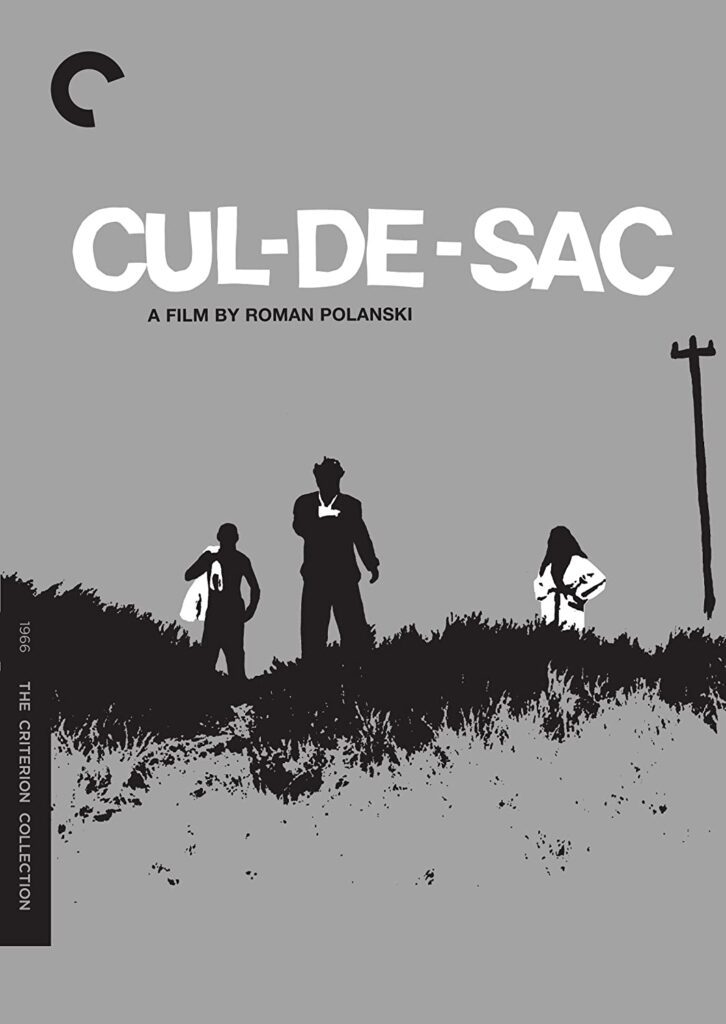

Cul-de-Sac is one of three films that Polanski made in England following the success of his first feature film, Knife in the Water (1962). The decade was a fertile one for Polanski. The first of the English-made films was the brilliant Repulsion (1965), starring Catherine Deneuve. Cul-de-Sac followed in 1966, to be followed a year later by The Fearless Vampire Killers. Polanski would close out this productive decade in Hollywood (where his life would soon be derailed) with Rosemary’s Baby (1968).

Cul-de-Sac opens on the aftermath of what we come to realize is a crime gone bad. As the film opens, we see a car approaching from a distance on a lonely road. A large, gruff-looking fellow named Richard (or Dickie, played by Lionel Stander) is pushing the car, one arm in a sling. Behind the wheel and looking worse for the wear is Albie (Jack MacGowran). Their surroundings are desolate, but Dickie surmises that the telephone poles stretching into the distance must certainly lead somewhere, so he goes off in search of the telephone they must surely be attached to at the end, leaving Albie behind.

Dickie eventually arrives at a run-down castle of sorts at the edge of the sea, seemingly deserted except for the dozens of chickens who seem to have free rein indoors and out. He makes himself at home and eventually comes upon the inhabitants of the house, an Englishman named George (Donald Pleasence) and his young French wife Teresa (Francoise Dorleac). Dickie phones a Mr. Katelbach – apparently his crime boss – for assistance, after which he ominously cuts the phone wires. He enlists the couple’s help in fetching Albie and the car from the dangerously rising tides and then settles in to await the help that he expects will soon be on its way.

A viewer might be forgiven for expecting this to turn out to be a garden variety thriller involving innocent home-owners put upon by bad people, but that’s not what Polanski has in store for us. By the time Dickie makes his presence known, we’ve already seen Teresa canoodling half-naked on the beach with a man who isn’t George, and we’ve seen George and Teresa engage in sex play that leaves him attired in one of Teresa’s silky nightgowns, his face painted clownishly in make-up.

What follows (and we already know that, under the circumstances, this can’t possibly have a happy ending) is a series of increasingly higher stakes episodes involving unexpected (and hilariously annoying) guests, a grave-digging, a disappointing realization for Dickie, and George’s ongoing humiliation and abasement at the hands of both Teresa and Dickie, which serves to continually ratchet up the tension amongst the three of them.

Polanski neatly keeps this film from falling squarely into any one camp; it’s part thriller, part psychodrama, and part black comedy. According to the essay by David Thompson that accompanies this release, Polanski described Cul-de-Sac in 1970 as “real cinema, done for cinema–like art for art.” Toward that end, everything works perfectly in concert here, from the unsettling score by Krzysztof Komeda, to Gilbert Taylor’s gorgeous black and white cinematography, which manages to convey the essence of the film’s title amidst the brooding isolation of its setting on Lindisfarne Island on the North Sea. The supporting performances are all adequate (MacGowran stands out by managing to convey a great sense of Albie given the limitations of his circumstances), but it’s Stander and Pleasence who are the most fun to watch.

As we’ve come to expect, any Criterion release is a rewarding experience in terms of both quality and extras. The transfer and the special features were all made with Polanski’s cooperation and approval. The film is presented in its original 1.66:1 aspect ratio, and the high definition digital transfer was created from the original 35mm master positive. The monaural soundtrack was cleaned so as to remove hisses and extraneous noises. The result is a film that is beautiful to look at, accompanied by a clean soundtrack that manages to preserve a general ’60s ambiance.

Extras include an interesting essay about the film itself and the production by critic David Thompson; two theatrical trailers; a TV interview with Polanski from 1967; and an entertaining 2003 documentary about the making of the film entitled Two Gangsters and an Island, which features interviews with Polanski, Taylor, and producer Gene Gutowski, among others.

Cul-de-Sac stands on its own next to Polanski’s best work and this release is a must-have for admirers of the director, or fans of ’60s cinema in general.