We’re well into the age of instant images; anyone with a smartphone is, or can be, a photographer and/or videographer. Perhaps because these handy photo-realistic images are so plentiful, they’re also ephemeral. One social media sharing site, Snapchat, turns this liability into a virtue, making the images its members send each other disappear soon after they’re viewed.

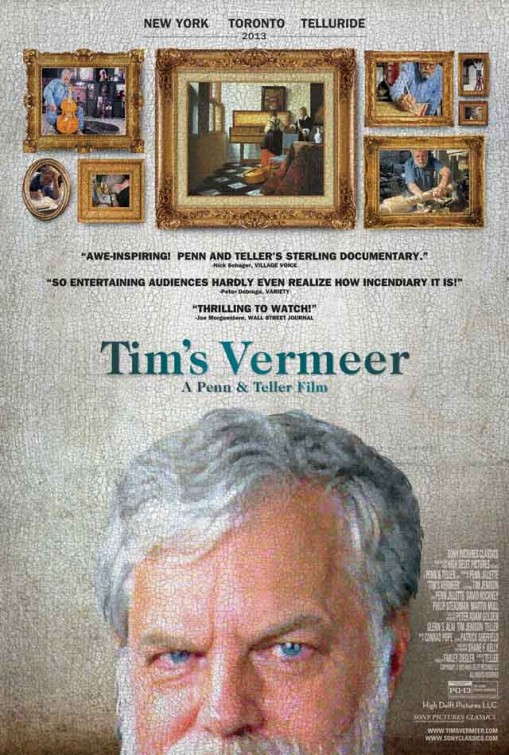

Tim’s Vermeer, a documentary about a guy who took the better part of a decade to re-create a famous work from the 17th-century golden age of Dutch painting, represents a drastic alternative to the ease and speed of image-making today. The film’s underlying message is that creating a truly lasting work of art takes time, patience and care – no matter what century you’re operating in.

The film, directed by Teller (of Penn &…) is a thought-provoking, clever and well-executed piece of work, but it’s not especially compelling all the way through. The film’s subject, Tim Jenison, perhaps inoculates it against such criticism by saying that the entire project is a lot like watching paint dry.

Jenison, a pioneer in computer-generated graphics for film and TV, doesn’t look the part of a man obsessed. He’s intense, sure, but funny and affable, with a gray-white beard that makes him resemble Santa Claus from certain angles. The project grew out of his desire to find out how Vermeer managed to paint so realistically (you almost feel you could grab hold of the patterned rug or walk on the tile floor in his painting) with only the technology that was available to him in the 1600s.

One possibility is that Vermeer used a camera obscura, Latin for black box, inside which images of real objects located outside the box can be projected onto a blank wall or canvas. Jenison, a tinkerer himself, comes to believe that a combination of mirrors and concave lenses were more likely parts of the artist’s bag of tricks, and that they were as important as the pigments he ground up and the brushes he used.

Tim’s Vermeer clearly and lucidly explains the technological aspects of Jenison’s theory. The initial section of the film, where Jenison – who admits right up front that he has no training as a painter – uses this technology to create a scarily realistic oil painting from of a photo of his father-in-law, is fascinating. We see this painting literally taking shape, tiny brushstroke by tiny brushstroke, with excellent editing by Patrick Sheffield and careful cinematography by Shane F. Kelly revealing how the process works while also indicating the “real” time it takes.

The film also held my interest when Jenison began to test the theory that Vermeer used similar technology. To paint his own Music Lesson, Jenison has to create, in a warehouse in San Antonio, Texas, not just the optical technology but the room in Delft, Holland where Vermeer worked, along with its period-appropriate contents. He has to make (or have made) the furniture, the clothing, the virginal (a type of harpsichord) and viola da gamba pictured in Vermeer’s painting, not to mention the roof timbers and the patterned windows. We see the advantages of being rich: you have both the money and the time to indulge your obsessions.

Jenison even gets to see the original painting itself, currently in Buckingham Palace, but only as part of a “no photos” deal with the Queen. In the film, his eyes are alight when he’s describing it, but we’re just seeing a talking head. It’s frustrating.

Also frustrating – and this becomes part of the point – is the actual process of painting his own version of the masterpiece, literally dot by dot, that takes up most of the film’s second half. The documentary crew shot more than 2,400 hours of footage, and there’s no question that even this most dedicated of amateur art/technology sleuths had many moments of mind-numbing boredom along the way.

To pump some drama into the doc, Tim’s Vermeer also tries to set up an “art vs. technology” conflict. Penn Jillette’s narration keeps asserting that some people (fusty historians and art purists) believe artists shouldn’t use technology, that this is somehow cheating or lessens the artistic value of the work. But the film pushes the “artists are inventors too!” proposition too hard. If Vermeer used optical gizmos to create his paintings, that’s only one element of the work. Who chose the subjects? Their composition? The time of day depicted? These all go into the impact a great painting can have.

Thank goodness for British artist David Hockney, still feisty in old age, who cuts through much of this crap. He spouts off some of the best lines, such as “You can’t paint with light, you have to paint with paint,” and “Paintings are documents that tell the story of their own creation.” Hockney, as a working artist, even posits a plausible explanation for why there’s no surviving documentation about Vermeer’s use of optics: that in the highly competitive art world of 17th-century Holland, no artist would put his methods and discoveries down on paper for fear they would be stolen.

Tim’s Vermeer is itself a document that tells the story of a work of art’s creation. The difference is that if you’re lucky enough to enjoy art and you feel like staring at a Vermeer, or a Rembrandt, or a Picasso for 80 minutes, you can. You can also move along. In the movie house, we’re stuck watching, but only rarely sharing, someone else’s fascination with how a lasting masterpiece came into being.