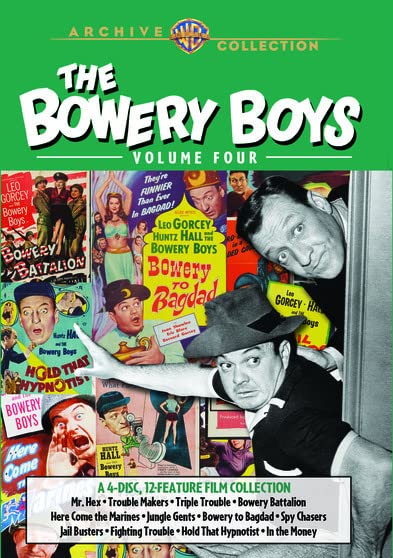

Nearly two years ago, the Warner Archive released a multi-disc set containing what had previously been something of a Holy Grail amongst classic B comedy lovers: The Bowery Boys: Volume One. The following year brought forth the next two volumes, teasing fans with the prospect of a fourth and final set that would essentially serve as the closest thing to a definitive collection ever – thus enabling anyone who still held on to a few shoddy bootlegged 16mm television prints a chance to upgrade once and for all. Well, it took nearly a year for that to become a reality, but at long last, The Bowery Boys: Volume Four is finally here.

Over the course of twelve years, the prolific Monogram Pictures/Allied Artists series cranked out an unbelievable 48 films. In fact, this amazing record has only ever been upstaged by the Spanish-language series of movies starring the late Mexican masked wrestler, El Santo; a sliver of useless information that conjures up a bizarre movie mashup if ever there was one! (Of course, if you include previous outings of The Bowery Boys, wherein an assortment of cast members appeared in variations of the gang – Dead End Kids, Little Tough Guys, and The East Side Kids – the grand total would reach nearly to the count of 100!) But as I sat and viewed the Warner Archive’s last assortment of low-budget comedies that made malapropisms a national pastime, I had something of an epiphany.

Yes, I know what you’re probably pondering: “Dear God, what the heck is this lunatic talking about now?” Here, in what can only be described as “odder” outings, it occurred to me that The Bowery Boys: Volume Four isn’t about what the series was during the set’s respective installments, but more of what they weren’t. For you see, boys and girls, as hard to believe as it may be, even a film series that only lasted for 48 movies had to occasionally hit an awkward point. These films were not necessarily “low” points for the franchise per se (though there definitely were a few over the course of time), but were simply just “different” in one fashion or another no matter how you looked at it.

The set begins with Mr. Hex (1946), Trouble Makers (1948), and Triple Trouble (1950) on Disc One, films containing what is generally regarded as the original line-up of the cast, such as Bobby Jordan (as Danny), William Benedict (as Whitey), and Gabriel Dell (as Gabe) – all of whom would disembark from the flight of the series in the first five years, mostly over objections that their characters were given less to do than the main stars of the series, Leo Gorcey as gang leader Terrence Aloysius “Slip” Mahoney and the venerable Huntz Hall as Horace Debussy “Sach” Jones. Although, in Mr. Hex, Sach sports a different last name: that of Sullivan (?). The writers were still finding their way here, which is evident in the decidedly East Side Kids-style story wherein the boys try to raise money to help out a friend in need (by hypnotizing Sach to be a prize fighter!).

The more traditional elements of the latter-day series were falling into place by the time Trouble Makers and Triple Trouble were made, though Bobby Jordan had already bid his fellow castmates adieu at that point – with Bennie Bartlett (and later, Buddy Gorman) replacing him. Gabe Dell once more portrays the man of many professions in these two movies (he had a different role in each film, sometimes even playing a bad guy), with the plots consisting of Sach witnessing a murder through a high-powered telescope in the first, and Slip and Sach being falsely accused as robbers in the second, who then plead guilty so that they can identify a prisoner who has been giving out secret messages to his gang on the outside; broadcasts an insomniac Whitey receives on his ham radio in the middle of the night.

And it’s a good thing Whitey had that much to do, as over the course of Disc Two, we witness Mr. Benedict’s cherished character becoming more of a minor one before bowing out altogether after the very first installment: 1951’s Bowery Battalion – one of two armed forces features on this disc, paired back-to-back with Here Come the Marines from the following year. While the first imitates the Abbott and Costello wartime comedies perhaps a bit too much at some times, it benefits from a fine supporting performance from Donald MacBride, the master of the slow burn, who gets the final laugh. In Here Come the Marines, the gang follows Slip into service when he’s drafted (wait, Slip drafted… into the marines?!), where they discover a subplot about a dead soldier and a crooked gambling ring.

The last film on Disc Two is perhaps the most unique, Jungle Gents from 1954, one of the first features made after pioneering producer Jan Grippo left the series, wherein Ben Schwalb took over and frequently employed Three Stooges writer/director Edward Bernds. And Bernds was indeed the man behind the camera for this as well as many future features, directing the boys in a story written by another Stooge writer, Elwood Ullman. Here, Sach develops the ability to smell diamonds thanks to some ultra-potent sinus medication (he has a big nose, you see), and it’s off to the African jungle (sigh), replete with backlot natives (including a young Woody Strode!) and a gorgeous jungle girl (Laurette Luez) who falls for Sach. Clint Walker makes his big-screen debut in an uncredited walk-on as a Tarzan-type fellow, and yet another Stooge regular, Emil Sitka, has a cameo (in fact, Emil appears in a number of these features in brief walk-ons).

Disc Three begins with another joint Bernds/Ullman venture, Bowery to Bagdad (1955). By this point, the new regime of Leo Gorcey, Huntz Hall, David Gorcey/Condon (Leo’s brother) as Chuck, and Bennie Bartlett as Butch had long been been established, and would remain in effect for several films. Here, Aladdin’s lost lamp finds its way in Sach’s hands, only to produce a cynical genie with a hankerin’ for some booze after all these years. And said genie is played by the forgotten, former co-star of many a fine Fred Astaire/Ginger Rogers film, the one and only Eric Blore. Though his teeth look most assuredly terrible here (thank you, remastered print), it’s a sheer delight to see him having a good time hamming it up in this, what would prove to be his final film. And once you see Blore and series regular Bernard Gorcey (Leo’s father, cast as the tormented sweetshop owner, Louie Dumbrowski) getting hammered together in a wine closet as the boys fight the baddies outside, you’ll agree with me.

Spy Chasers (also from ’55), the second film on Disc Three, features another odd supporting performance: the great Sig Ruman – perhaps best remembered as a protagonist of The Marx Brothers – as, wait for it, a good guy. In fact, he’s the King of Truania (which turns out to be Louie’s home country), temporarily ousted from his homeland while Louie’s general brother tries to clean the country up of rebels. Mel Welles (who not only played Mr. Mushnik in Roger Corman’s original The Little Shop of Horrors, but who also went on to direct the sleazy Euro class-ick Lady Frankenstein) has a small uncredited bit.

But perhaps the biggest oddity of all is found in Jail Busters (another from 1955), which begins with Chuck (David Gorcey/Condon) starting out in what can only be described as a Gabriel Dell role, employed (sacrilege) as a reporter who goes undercover to investigate corruption in a local prison, only to be beat to a bloody pulp and being forced to spend the remainder of the film unseen in a hospital bed. Thus, the feature relies on Slip, Sach, and Butch to carry the story, who go to jail at the behest of a crooked reporter (Lyle Talbot) and sort of do an expanded Three Stooges short throughout courtesy, of course, writers Bernds and Ullman. Fritz Feld has a role as a prison shrink, Percy Helton (who would later become the brief one-off replacement for Bernard Gorcey) is the warden. William Beaudine directed this, the last film in Volume Four to feature just about every one of the original gang.

And it is on Disc Four that we witness three of the final seven Bowery Boys features to be made after series star Leo Gorcey had quit following a bout with alcoholism following the untimely death of his father Bernard and a fight with studio execs asking for a pay hike. So, starting with Fighting Trouble (1956), we see the debut of Huntz Hall’s new partner in crime, Stanley Clements as Stanislaus “Duke” Covelske. Clements had previously appeared in several East Side Kids films, so he wasn’t completely unfamiliar with the territory. But with everyone save Huntz Hall and David Gorcey/Condon out of the picture (literally) owing to death or dissatisfaction, nearly everything about the series had to be revamped – with a new line-up of eponymous heroes (Hall, Clements, Gorcey/Condon, and Danny Welton – who only made one appearance as a Bowery Boy) and even a new base of operations (a rooming house, run by Queenie Smith, taking over for a previously seen Doris Kemper) in play.

Thankfully, Clements sets out to not mimic Leo Gorcey’s Slip Mahoney, but rather to take on the part of a big-brother type for Sach, who is constantly annoyed by the latter’s gimmicks. In Fighting Trouble, Sach’s gimmick is photography – and a news editor’s proposal of snapping a photo of elusive crime figure Frankie Arbo (Thomas Browne Henry) couldn’t come at a better time when Danny loses his job after he’s (wrongfully) accused of theft and promises to pay his former employer back the money lost. Eventually, Sach and Duke come up with the foolproof plan for Sach to impersonate a Chicago gangster: a surefire recipe for disaster. Adele Jergens (The Amazing Colossal Man) is the femme fatale of the tale as Thomas Browne Henry’s gunmoll.

In Hold That Hypnotist (1957) – a now rare outing from the final days of The Bowery Boys that wasn’t helmed or handled by Misters Beaudine, Bernds, or Ullman – we are privy to one of the rare instances comedian Huntz Hall was given the opportunity to show a slightly dramatic side of his abundant acting abilities. When the boys’ landlady makes an appointment with an infamous hypnotist (Robert Foulk), they smell the foul stench of a trickster at work, so they crash a press party to expose the phony doc. Alas, an attempt to hypnotize Duke winds up working on Sach, who reveals he was an English tax collector in a previous life, and who knows the whereabouts of Blackbeard’s treasure. It is here, via flashbacks, that we get to see a side of Hall that we hadn’t truly experienced since the Dead End Kids days. Jimmy Murphy is the fourth titular lad here, and Mel Welles plays Blackbeard.

And finally, ladies and gentlemen, Disc Four ends with what proved to be the very last film in the series, In the Money, the only title of the legacy to have been released in 1958. Interestingly, this and the previous film, Up In Smoke, were made solely because of Hall’s contract. And wherein that entry was a significant highlight from the Slip-less period, In the Money also has something going for it. The story has Sach hired by a group of diamond smugglers (including Leonard Penn, co-star of several Columbia serials, including the 1949 version of Batman and Robin) to unknowingly be the bodyguard for the mule for a cache of hot ice: a show poodle. The rest of the gang (now with the much more likeable Eddie LeRoy in place as the fourth man) tag along, only to wind up being chased by Scotland Yard (led by Paul Cavanagh).

Silent film comedian Snub Pollard has a brief bit as a Yard valet here, and television actress Patricia Donahue has one of her very rare film roles here as the bad girl. Writers Al Martin and Elwood Ullman seem to be paying their respect to the series here, making sure to give all of the boys at least something for audience members to walk away with, including what becomes one of Duke’s most memorable (last) lines: “I have my right, and this is it!” Likewise, director William Beaudine was a most-appropriate choice to guide the half-new cast through their grand finale, even taking a little extra time to pan across Eddie LeRoy, David Gorcey/Condon, Stanley Clements, and Huntz Hall during the very last scene before giving the one and only performer who had been there since the very first film – the mega-talented Hall – one last chance to play the fool for all to see. God bless ’em, every single one of them.

Like the last three volumes, the Warner Archive Collection presents the movies with clear Mono English soundtracks in their original theatrical aspect ratios; the first couple of (older) entries are in their native 1.37:1 format, before the remainder shifts to 1.85:1 widescreen about halfway through the set. All of the movies have been remastered for this set (with initial releases actually pressed to DVD, as opposed to DVD-R) and nearly every movie present is in beautiful condition (the source used for Mr. Hex was not the best, but was probably the only one available, so we can’t be choosers). What’s more, the guys and gals at the Warner Archive have dug even deeper into the vaults in order to bring us a bonus of assorted previews. Yes, that’s right, we get trailers for this set, kids – 28 in all, in fact – spread out over the first two discs.

So even if you’re very much Team Slip (really, it wasn’t Stanley Clements’ doing, folks – give the poor guy a break already!), you’ll want to get this final set for one reason or another. Maybe you just want to complete your collection (and you should). Or perhaps you’re curious to see Eric Blore in his final film outing. Perhaps you’re a diehard Emil Sitka fan, or you simply just can’t get enough of David Gorcey/Condon’s handsome face always being right behind somebody’s arm. And yes, there’s that matter of twenty-eight trailers – most of which haven’t been seen in decades – also being included in this final hoorah for what was arguably the greatest, longest-running comedy series ever made.

Highly recommended.