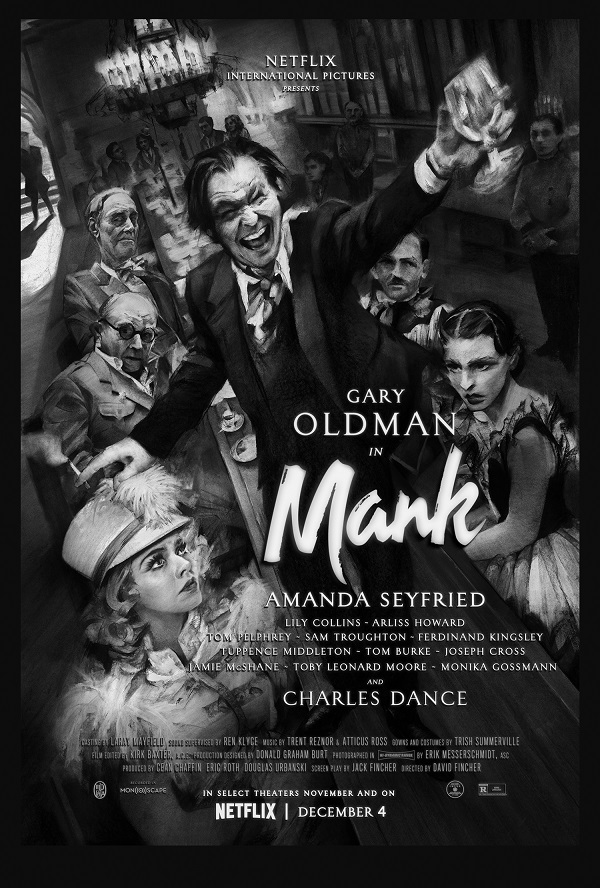

In the past few years, Netflix has enticed some of our best filmmakers—Joel & Ethan Coen, Alfonso Cuaron, David Fincher, and Martin Scorsese—to its stable, and no surprise: Decently paid, and promised final cut (or “creative control,” however that shakes out), these directors would be foolish to resist such a deal. The results of their labor, we should note, have so far not disappointed. Cuaron’s Roma (2018) was a passion project of the first degree, shot in black & white—a career best for the gifted director. And while the Coens turned in a fun but mixed Western anthology, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018), that rivals anything they did in the Aughts, Scorsese gave us The Irishman (2019), a confident but extended look at the mob that for all its wicked comedy was a sad take on the pain of a long life spent in service of death and betrayal. Unwieldy in its length (it bored many a viewer), it’s the epic Scorsese wanted to make. Now Fincher, the chief brains and talent behind two Netflix shows (House of Cards and Mindhunter), is back in the feature-film ring with a project he has long doted on and wanted to bring to the silver screen (and which, outside of a limited theatrical run, he will have to make do for a streaming service and its multitude of subscribers instead): Mank, a semi-factual dramatization of legendary scenarist Herman J. Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman, who gained weight for the part and escapes into his performance), based on a script by Fincher’s late father, journalist Jack Fincher.

Just as Netflix pumped The Irishman as can’t-miss Oscar bait, so have they offered Mank as their prestige pic of 2020. It is a good film, through and through, and while its impeccable craft is nothing less than surprising for a director of Fincher’s repute, I cannot say that (while it aspires to greatness) it achieves masterpiece status, or any real notoriety.

There is always the universal regard for, and fascination with, Citizen Kane—the 1941 film Mankiewicz and his pal, doomed boy genius Orson Welles (Tom Burke), schemed to foist on an unsuspecting public, and which is now seen as the greatest American sound picture ever made—that we can lean on as one reason Fincher made this film. Mank charts the conception of Kane’s script. More than any film before or since, Kane wrote the text on how risk-inherent the greatest cinema can be, and how treacherous it often is to break open the manifold possibilities the medium offers. For a keen cinematic eye like Fincher—whose output to date is a case study in using the power of film to titillate and rouse filmgoers’ interest in dangerous situations and not so likable characters—his chosen vocation and the self-expression it affords might not exist had Kane not happened. So there is that. The other reason I suspect Fincher made Mank is not just familial but speaks of principled artistic impulse: His father saw, in the storied making of Kane, a portrait of a lovable but flawed writer who thumbed his nose at the system responsible for his livelihood—all to be not just the last scallywag standing, but to use his talents for a higher cause. In Mankiewicz’s case, it secured the ruin he was (by the time he started in on Kane’s first draft). After Kane, he wrote only a handful of pictures; and yet, he and Welles won an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay, and his legend is complete.

Herman J. Mankiewicz did not, of course, dream up Kane alone. In her scandalous but erudite 1971 essay, Raising Kane, the late, influential film critic Pauline Kael suggested he had. (Kael had her own not-so sly agenda, to enshrine the beleaguered underdog [the writer, in this case] and burst the bubble of the auteur school of film journalism, gaining what notoriety she could.) But Mank runs with the theory, minimizing Welles’s contribution to Kane by mostly keeping him offstage (he visits Mankiewicz in the hospital, calls him at his desert hideaway, and joins him there once Mankiewicz finishes the first draft), and zeroes in on the events that inspired or led Mankiewicz to this assignment.

Those familiar with Kael’s essay will recognize the man Fincher’s film examines, even some witticisms he uttered. Jack Fincher’s script presents a little man of not a little generosity, with a crippling gambling addiction and a large appetite for booze—a consummate wit capable of charming back-lot security and the toast of San Simeon, the gaudy (some would say ridiculous) fortress that belonged to newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance, whose tight-lipped, crag-faced demeanor is perfection), at whose side he insisted this “Voltaire of Central Park West” dine, drink, and be merry (to serve, in effect, as court jester). The hobnobbing comes easily to Mankiewicz. In no time at all, his introduction to Hearst and Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried)—Hearst’s prize doll and a would-be starlet—through her nephew, screenwriter Charles Lederer (Joseph Cross), has him in the catbird seat. Long since beloved, but plainly and casually dismissed as a sort of liability, Mankiewicz and his lifeline to the pictures (and the relative ease with which he can erase his gambling debts) flows back to Hearst, who we learn funds half of Mankiewicz’s salary at M-G-M. Had Hearst acted otherwise, M-G-M mogul L.B. Mayer (Arliss Howard) suggests, the raconteur-rapscallion would have been finished long ago. But this comes late in the picture, after a series of incidents culminates in what can only be described as a conflict of conscience for Mankiewicz. He embraces his buffoonery but (we are to understand) drowns his sorrows.

Posited here is the notion that he feels guilt for having planted the seed in producer Irving Thalberg’s head that M-G-M could run phony newsreels designed to sway public opinion against Upton Sinclair (Bill Nye!), a socialist who loses his bid for the California governorship. The man who made those newsreels? He is Mankiewicz’s friend, and blames himself for Sinclair’s loss, even threatening suicide. Foolishly, Mankiewicz thinks he has saved his friend—a sad circumstance which underpins Mankiewicz’s desire to get back at the dream factory (i.e., the muckraker Hearst and all his cronies) he believes responsible; to use his scripting gifts to do for Hearst, Mayer & Thalberg what they did for Sinclair. This ill will against Hearst does not bear scrutiny, unless Jack Fincher uncovered something no one else could; but it incites incident; it motivates Mankiewicz to artistic revenge, which any informed cineaste will see coming a hundred miles away. Hearst could not prevent showings of Kane; but he could, and did, make life difficult for people, most notably Welles, who never again made a brilliant film with the full backing and trust of a major studio. Kane, Mank suggests, came not just of impishness, but of integrity. Of standing for something and using one’s creative genius to do it. Bosh, I say—total bosh.

Right from the start of Mank, though, the sheer craft of the thing lifts us. It buzzes like a love letter to cinema—which, in its giddy and headlong way (its bold and experimental toying), Kane proves as a good enough reason for its being as any. In fusing stylistic reference points with all the digital modernity Netflix money can buy (e.g., black & white color, false reel change circles, monaural audio, and sharply paced screwball banter; introducing flashbacks with self-conscious slug lines), Fincher has not made a 1940s-ish movie so much as taken a cue from Kane, incorporating these touches onto a canvas where it seems everyone is playacting at making an older movie. This exuberant look-ma-no-hands glee, according to Kael, was Kane’s chief charm—the almost palpable sense of fun Welles had with the cinematic machinery at his disposal; the way it invited the audience to share Welles’s wonder at the clockworks, and to enjoy the film as a brazenly theatrical display of showmanship bigger than the sum of its unoriginal parts (e.g., in Kane, Gregg Toland’s masterful cinematography wasn’t the first time American movies had used deep-focus cinematography, nor was Kane the first time an American feature film had stitched together a fake “March of Time” newsreel. Originality, my friends, is overrated). But Fincher need not impress us with his craft any more than a zebra warrants stripes—he submitted that term paper, if you will, a while back. What he has done in Mank is align himself spiritually with Welles & Mankiewicz, monkeying with history and technique to rebuke the mucky-mucks—in this case, Hollywood as it was then and may be now. Fincher focuses on Mankiewicz’s lukewarm cri de coeur (at least as Mank envisions it): holding oneself accountable for one’s behavior—of confronting guilt and using one’s talent to call out the factory system in which one has flourished. When you consider the risk inherent—that, in mocking Hearst and his circle by making him the subject of an arrogant wunderkind’s debut splash, Mankiewicz was burning all his bridges, (such was Hearst’s clout)—the daring of Kane is something to behold. (Granted, we are not talking about people who stood in the breadlines, barely able to rub two cents together; so we must not exaggerate the heroism, risk, or sacrifice involved.) Mankiewicz may have sensed he had nothing to lose; but no one knew the Kane gamble would pay off with the critics and do even modestly at the box office. Washed up, Mankiewicz was seen as yesterday’s news. No one could have known Kane would assume the air of a classic.

Mankiewicz’s script for Kane impresses for many reasons. But one of its great accomplishments is that it offers a glimpse of Kane the person even as it strings up vignettes told from multiple viewpoints. The truism at the heart of Kane—that we cannot ever fully know a person; that we can try to, but total knowledge of another person evades—colors Mank as well. Fincher’s film gives us a sense of who Herman J. Mankiewicz was, shot liver and all. At first, I questioned Jack Fincher’s choice to avoid narration outright, which might have created a more convincing, and efficient, sense of interiority (something a great novel can do, no matter how sparsely worded). Then I watched Mank a second time and went with the movie’s scheme. We are not meant to be that close to Mankiewicz and his thought process. Following the Kane model, David Fincher is more invested in skipping through time and allowing us to see things for which Mankiewicz was present; but distance, and ambivalence, owns (even obsesses) Fincher: the distance of Mankiewicz from his conscience, of a dream factory’s illusion from the screwy, even slimy, politics on which it rests. (The climactic dinner scene at San Simeon is a perfect explosion [a fitting purge] to which we realize the film has been leading all along, and from which the rest of Mank’s story, and Kane’s by extension, feels logical. How apropos that, before the last dinner guest has left, Mankiewicz pitches the Kane project to Hearst.)

All of this helps inform Fincher’s choice to turn Mank into a self-consciously old-feeling film. He uses the tricks of the trade to envelop us in a world and way of life that we at once associate with the films from the era it depicts, and yet his technique underlines the distance that is his subject. Not every scene works, and one performance (Seyfried as Davies) tends to grate, maybe on purpose (she almost seems too on the nose of the playacting tone Fincher encourages). I also wish Mank had resisted the idea that Mankiewicz’s drive to write Kane lay in contrition. I more than suspect the actual man (with Welles and others egging him on, chortling just as hard as Mankiewicz) had something less noble than a personal tragedy in mind when he decided to use Hearst’s fabricated style of journalism against him. Mankiewicz was just being true to his destructive self. The big crack-up, he put it all on the line. He risked it all to have the last word—just to have a good guffaw and show the world how clever he was.

Mank manages (like a drunken sailor) to sidestep mawkishness. As a film about something, that relishes the opportunity to drop the viewer in a fully imagined and handsomely mounted 1940—and to give us some “dirt” on what led to the birth of Citizen Kane—it gels. Some of my film-loving friends find it a chore to sit through. This, even though Mank mostly zips by like Wile E. Coyote himself. The movie is not to all tastes; it will not be everyone’s cup of joe; you almost need to have the same obsessions Fincher does (I do, and I even appreciate the other winsome [and much maligned] Netflix dish on Tinsel Town, Ryan Murphy’s Hollywood, that surfaced this year. It swan-dives into a bawdy Hollywood Babylon vibe, even if it trips by retrofitting a fashionable redemption narrative). Mank is still one of the best productions released this terrible year, and I expect it to win zero Academy Awards. What a fine validation that could be.

1 Comment

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

[…] Mank | Review […]