Written by S. Edward Sousa

The Murder City Devils, one of the great outsider rock bands of the past two decades, once sang “Took a city like New Orleans to kill a man like Johnny Thunders / A man who died with a guitar in his hands.” It’s the city as beast slaying Thunders, The New York Dolls’ guitarist and former Heartbreakers’ front man who even in death still slings six-strings. Named after its subject, the song’s as tough as Thunders whose music couldn’t be pried from his cold dead hands. Solidifying the man’s mythos as he drifts off into death they scream, “And the very next song it was gonna be a hit…and all those young girls are crying, crying, ‘Why, why, why Johnny Thunders.’” In a lot of ways this the arch of Thunders’ life, living on the plateau of prominent obscurity only to become a rock n’ roll sacrifice. But you can’t help wondering as Murder City front man Spencer Moody yells, “I say, ‘Go, go, go Johnny Thunders,’” is this a tribute or a goodbye salute to a man for whom life held no payoff, but in death found immortality.

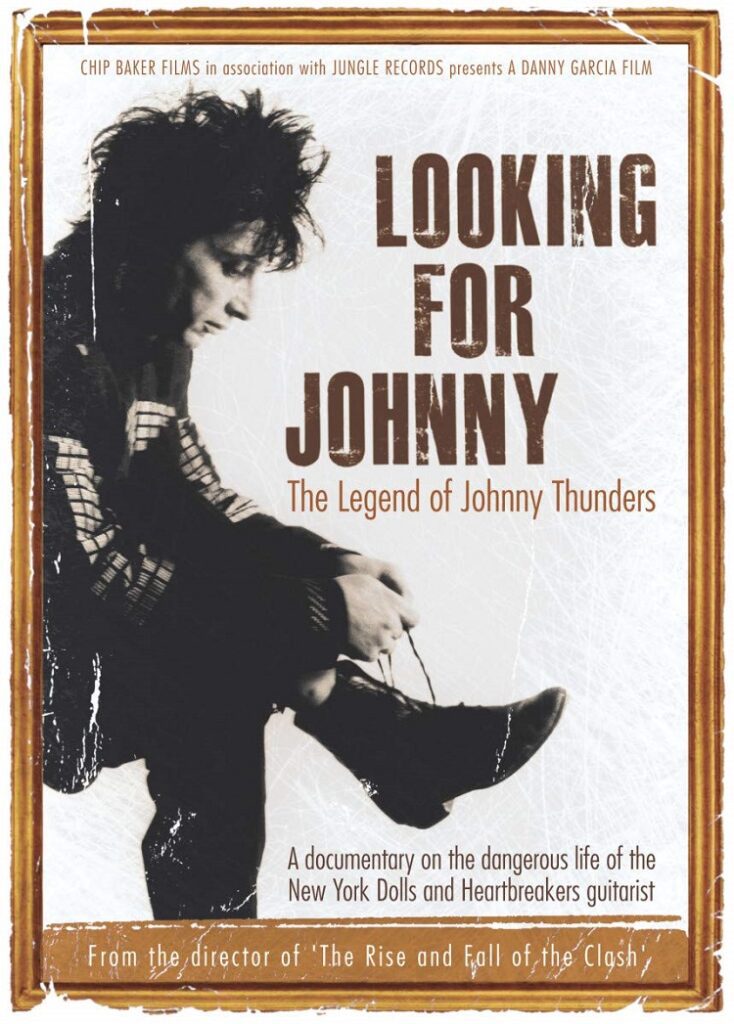

Spanish filmmaker Danny Garcia has this headstone hurdle to leap in his new documentary Looking For Johnny, out now on DVD through Chip Baker Films and Jungle Records. The specter of this legend haunts the space between the mainstream and the underground—Thunders’ Chuck Berry-esque guitar licks and heart-on-his-sleeve lyrics are a poltergeist to reckon with. But Garcia has the tenacity to see it through, he staked documentarian claim with The Rise & Fall of The Clash, a concise and in-depth look at another lingering ’70s musical force. But while in that film Garcia sought to unpack the tumultuous ending of The Clash and the tension between various members, Looking for Johnny is an empathetic and honest take on a talented artist whose thirst for human connection and personal intimacy could never be quenched by rock n’ roll, women, or drugs.

The documentary charges through Thunders’ life, starting with his childhood in a fatherless New York City home surrounded by his mother and two sisters. Thunders began playing out at age sixteen, first with The Reign then with Actress, who morphed into the New York Dolls. Johnny and his sisters got schooled in rock n’ roll at the Fillmore East and seeing the Stones at Madison Square Garden, where they make a brief appearance in Masyles’ film Gimme Shelter. Old friends, like Dolls’ guitarist Sylvain Sylvain and bassist Peter Jordan, talk about the musical brotherhood and love of dope Thunders and Dolls’ drummer Jerry Nolan shared. Sober-minded pals like photographer Bob Gruen and Heartbreakers’ bassist Walter Lure pop-in to dissect Thunders inability to hold it together long enough to maintain relationships or find commercial success. This is where old managers like Malcolm McLaren and Marty Thau pop-up to talk shop about the nature of Thunders shortcomings. That’s the thing with Thunders, the guy wrote soul-crushing classics like “Born to Lose,” “I Only Wrote This Song for You” and “You Can’t Put Your Arms Around a Memory,” a cut so sad and so memorable Bob Dylan once remarked he’d wished he’d written it. But these songs never catapulted him beyond cult status.

From here it’s a hodgepodge of ex-girlfriends and old pals like Suicide’s Alan Vega, Biographer Nina Antonia, and Lenny Kaye, a man whose dense knowledge of rock n’ roll warrants a documentary himself. Even Billy Rath turns up—he’s the bass player who replaced Richard Hell in the Heartbreakers and helped bill the record label for cocaine during the LAMF recording sessions. Charming anecdotes, both in the film and on the deleted-scenes reel, give depth and personality to the fragmented man Thunders was. What emerges through Garcia’s film is despite all the inebriation, debauchery, or delinquency Thunders was not erratic guy, but a rather sweet and sad man whose only hope of communicating with the world came through his guitar. His drug use takes center stage in his downfall, but there’s never a deluge of irreparable incidents to alienate him from his friends. Sure, he ends up in Detroit with Wayne Kramer doing Gang War just after Kramer does a bid for slinging cocaine, and yes, he’s estranged from his wife Julie and all four of his kids, but these are side notes to the main theme, Thunders was never sober enough to get his act together. Even towards the end of his life, Thunders put together a soul style revue called The Oddballs, who despite their full-bodied sound never connected with a larger audience.

And it’s his death in a New Orleans hotel room that lingers throughout the narrative, it’s sordid, drug-soaked details lend an air of mystery the film attempts to work out. Garcia relies on the footage of those who were there—visionary punk filmmakers like Don Letts and Rachel Amodeo or French director Richard Grandperret who directed Thunders in Mona et Moi. You see the physical changes wash over Thunders from the shifts in rock fashion—teased hair turns to a foot-high quaff—and from the years of rampant drug use as he thins out and grows paler over time. In the background Garcia paints a portrait of New York City in the 1970s and ’80s when the city was no more than an urban jungle seething with racial and class tension beneath every facet of its culture and society. He makes sense of a stunned and saddened Thunders as he emerges out of this dismal and turbulent setting into a wider world he struggled to find a place in.

Somewhere in the middle of the documentary, Thunders is onstage in front of a packed theatre in Sweden barking at the crowd between songs. He turns to them in a bit of a fog—one could only guess drug induced—and shouts “So what do you kids do for entertainment?” He pauses, sizes them up, and shouts, “What the fuck’s the matter with you kids anyway!?!” For a moment Thunders appears pitiful, mumbling angrily in a haze of dope, but then he tears into the next cut and you remember how much he sacrificed in attempt to achieve his vision. You can’t help but think back to Spencer Moody’s directive for Thunders, that perhaps he’d given us enough and in death he’d achieve an alluding emotional connection so many listeners in his songs. And then you stand there screaming, “Go, go, go Johnny Thunders!”