Comedy doesn’t tend to get the respect of drama in movie writing. Like horror, its effectiveness depends on whether or not the audience laughs – it demands, when done right, an immediate physical response. It’s hard to write oneself out of having laughed at a comedy a writer doesn’t want to enjoy for whatever reason, or to write oneself into praising a comedy that didn’t raise a yuck. Dramas have more stuff for writers to write about, and writers are the ones who make the lists of what’s important in cinema and what isn’t.

I’ve seen reviews of 1959’s Good Morning, Yasujiro Ozu’s rare later-career foray into comedy (which, like crime dramas was something he worked in regularly in his early career) that dismiss it as a sitcom. It has some of the narrative form of a sitcom – there’s a family, each of whom have their own little stories that coalesce into the larger whole, it strives for jokes rather than dramatic beats, and the dramatic stakes are pretty low. But this dismissal ignores that, while going for laughs rather than tears, Good Morning still finds moments of poignancy in the typical Ozu style, and is suffused with the warmth that pervade all his movies. Good Morning (called Ohayo in Japanese) is primarily focused on the Hayashi family – a husband and wife and two boys who live in a small Tokyo suburb. Their little community is close knit – perhaps too close knit: everyone’s front door is just a step or two away from everybody else’s, and one choice word (or lack of a word) in one conversation can start rumors that fly around practically instantaneously.

There’s a local couple who stay in their bedclothes all day, and have a TV that the kids come over to watch all the time. The boys of the community have decided, in that inimitable adolescent way, that farting on demand is now the height of sophistication, and so they all demonstrate their prowess as regularly as possible (one kid can’t get himself to do so without going a little too far, and is regularly making extra trips home to replace his underwear). The Hayashi boys are addicted to watching sumo wrestling on TV, but their parents don’t want them around that scandalous couple. From the boys’ perspective, the solution is simple: buy a TV. The father’s steadfast refusal to do so leads the kids to a shouting match with the old man, and eventually the Hayashi boys take a vow of silence: they will not speak until they get what they want.

This act of rebellion cascades into causing problems with the neighbors (who think the boys are snubbing them because of something Mrs. Hayashi said to them) the school and eventually the law. There’s a minor crisis when the boys appear to have run away, but as anyone familiar with and who appreciates Ozu will anticipate, not much comes of it. In fact, if there were a single central thesis to all of Ozu’s latter work, it might be that: not much comes of it, it being life, hopes, and dreams, whatever. A master of domestic drama with a deep loathe of anything approaching melodrama, Ozu makes his movies out of small moments, temporary crises, little decisions that all add up to life.

Ohayo means “Good Morning” and it’s just one of the little meaningless bits of social lubricant that help people go through the day. Good Morning is about how minor breeches in this etiquette can mean the difference between a friend and an enemy, between a quiet neighborhood or a rancorous one. There are two middle generation characters, older than the boys but not as old as the parents, who are clearly attracted to each other (we know this because they are the two prettiest people in the picture, and they have conversations. Movies aren’t rocket science) but can never bridge the gap of politeness enough to acknowledge it. They rely on “good morning”, “how are you”, “fine weather we’re having” and that’s as far as it goes.

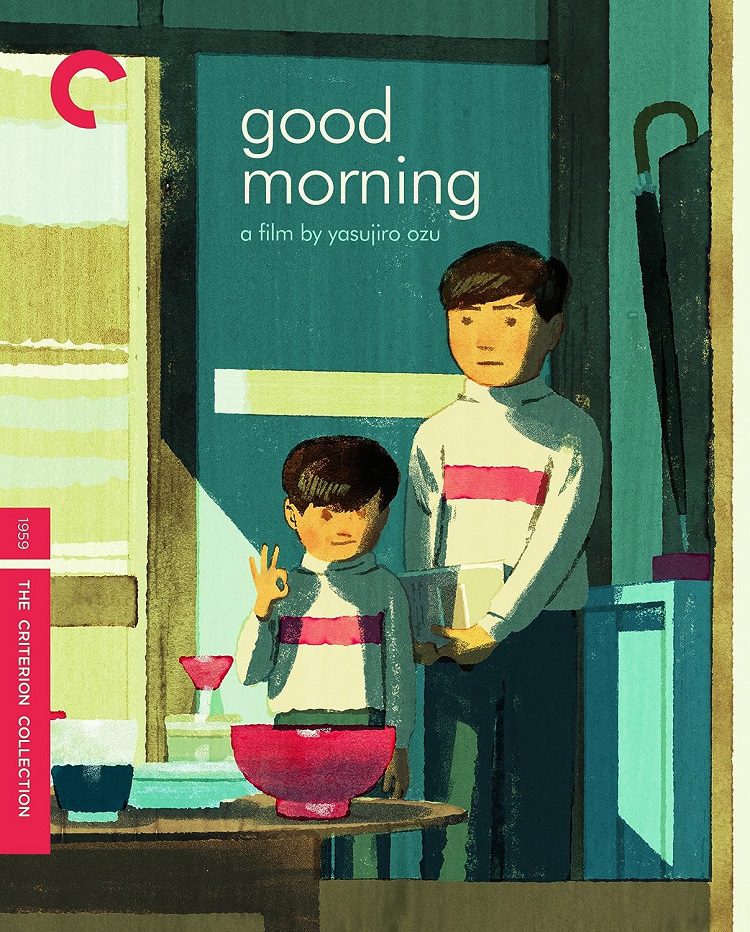

While there’s a general sense of light-heartedness to the entire film, I found most of the real comedy came from the kids – in particular, the youngest Hayashi brother, Isamu, played by seven-year-old Masahiko Shimazu. He was a child actor in several Ozu movies, as well as in Kurosawa’s High and Low. His compact features and build, along with his natural sense of comic timing make practically every gesture hilarious, without ever descending into obnoxious movie “cute kid” antics. His dark, serious expression hardly ever changes (except when he manages to break wind on demand, then he’s got a grin on his face). Dressed in the same clothes as his brother, just smaller, the image of the two, which little Isamu watching and then copying everything the older Minoru does, is the film’s most reliable sight gag.

Even in comedy, Ozu’s latter-day style is present: locked-down cameras, conversations that cut between straight-on shots of the actors, looking right into the camera. It’s never been a style that’s presented me with any problems enjoying Ozu’s material, but it is a stumbling block for some. It’s a style that Ozu refined after a lifetime of making movies. The Criterion Blu-ray release of Good Morning contains, among other extras, a second film that is cited (without much justification) as a movie Good Morning is a remake of, I Was Born, But… A silent from 1933, I Was Born, But… is also a comedy about two brothers who eventually go on strike against their parents, but its tone is different, its story darker (and significantly more focused on the brothers – in Good Morning the Hayashi boys might get the most screen time, but most people in the neighborhood get scenes to flesh out their situation and relationships). Interestingly, there is far more dynamic camera movement and editing in this old film than its supposed remake 26 years later.

Also on the disc is an excerpt from another Ozu movie about rebellious youth, A Straightforward Boy, a video essay about Ozu’s humor by David Cairns, and a short discussion of both Good Morning and I Was Born, But… by David Bordwell, who has written extensively about Ozu, including a full-length book examining the director’s films.

Good Morning may not be the first Ozu movie I’d show a first-time Ozu watcher. It is steeped in the man’s particular style and cinematic language, rhythms I found welcome and familiar, and enjoyed the change of pace from the director’s starker, more tragic films like Tokyo Story or Late Spring. But maybe it’s in the nature of comedy to feel slighter, less “important” than the sadder movies. For my money, Good Morning contains many of the same pleasures of Ozu’s dramas: the humane sympathy with every character and the wistful sense of resigned pessimism about human nature that never veers into cynicism. It’s a lovely film, happy to find some small poignancy is small, real moments.