Written by Kristen Lopez

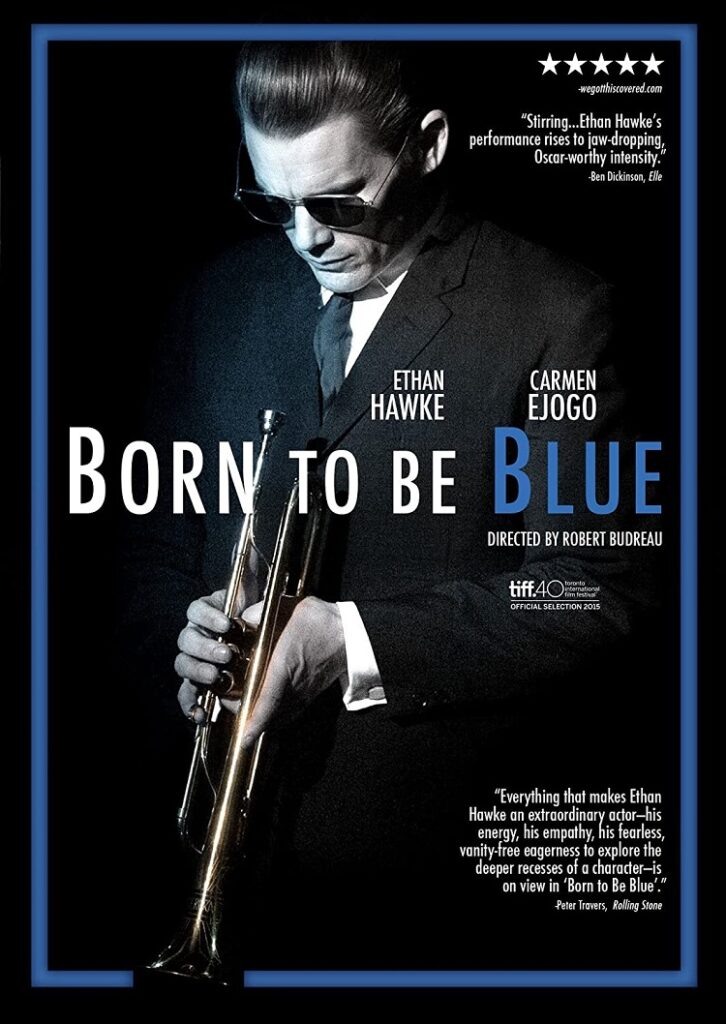

A week seemingly filled with biopics, from the Hank Williams story I Saw the Light to Don Cheadle’s Miles Ahead, director Robert Budreau’s Chet Baker biopic, Born to Be Blue, ironically finds itself in competition with Cheadle’s tale, both recounting the muddy lives of famous jazz musicians. (Born even has Baker (Ethan Hawke) ask a fan who’s better – him or Miles Davis – an unintentionally fun poke at the two film’s release this week.)

But on its own merits Budreau’s tale is an unconventional, if still remarkably straightforward, walk in Baker’s shoes, recounting his struggles with addiction and struggles to get back on top propelled by a momentous performance by Ethan Hawke.

While making a movie about his life, acclaimed trumpet player Chet Baker (Hawke) struggles to stay sober and get back to his peak after losing his embouchure, preventing him from playing trumpet like he used to.

As with the likes of Billie Holiday or Charlie Parker, many novice audience members hearing the name “Chet Baker” will probably only know he was a musician who died horribly – if that. As opposed to taking the typical “birth, lived, died” approach to biopics, Budreau, who wrote and directed, focuses on Baker’s life after his success and time at Charlie Parker’s Birdland – a location Baker lusts to return to as a means of proving his relevance and success.

With much of Baker’s history we’re given snatches, individual moments or compilations from his life. His performance at Birdland starts audiences, and Baker, on the highest precipice so there’s only one way to go. Baker chases his dream of returning to Birdland as much as he chases the white dragon of heroin. In fact, Budreau spends a lot of time comparing the peaks of fame to a literal intoxicant, putting Baker on a race for something to fulfill him at every moment, whether it’s drugs, the love of a woman, or success, creating a multilayered history for the character without having to fall on showing us specific scenes reenacted.

Interestingly, the film becomes a movie within a movie, with Chet playing himself and his girlfriend, Jane (an utterly jaw-dropping Carmen Ejogo) playing both his current flame as well as a self-confessed combination of all his wives and lovers in the film. Using black and white for the film and color for reality, there’s still an unspoken ambiguity regarding what we’re watching. Where is the threshold between fantasy and reality? Does Chet know that himself? The movie abandons the filmmaking conceit fairly quickly, but towards the latter half of the film, there’s an awareness of the conventions of the biopic. The movie, both the one Baker films and the one we’re watching, is a record of his talent – both become testaments of a past Baker can no longer reach.

And unlike other biopics where the character is mired in the squalor of addiction, everything looking like a retread of Trainspotting, Baker’s heroin addiction remains on the fringes, despite knowing it stayed with him the rest of his life, eventually killing him. Baker’s true colors shine in the sad descriptions of his time on heroin. For him, being high on drugs is the only time he’s “happy,” a terribly sad, if not honest, summation of drug addiction. As with the presentation of Baker at his peak, the soundtrack of Baker’s musical compositions dominate the soundtrack, playing as if in his mind as the elusive high he can’t catch but always remembers. Budreau captures the feeling of success, and the tormented hunger that comes from wishing to recreate it.

Like Michael Fassbender in Steve Jobs, Hawke doesn’t undergo any remarkable makeup effects to look like Baker. Much like the tone, it’s all about the proper feelings and emotions which Hawke simply defines! On the movie set he’s meek and quiet because after his fall from grace he’s perpetually terrified of disappointing people – and that’s what he does at several points throughout the film. His honesty comes off coarse, never as revelatory as he believes it to be. His relationship with Jane anchors the film, and it’s only a matter of time before their two very different lives fall apart, not from anything over-the-top, but because they’re two individuals with vastly different dreams.

You expect a Sid and Nancy-esque implosion in a biopic of this nature, and Born to Be Blue benefits from a less bombastic relationship, aided by the luminous performance by Carmen Ejogo. The woman’s proven herself more than capable of playing a tough woman of a different era with her role as Coretta Scott King in Selma. As Jane, and Baker’s ex Elaine in the film within the film, she spells it out she has a distaste of being “more than the women of Chet Baker.” Though her mere presence in his life fulfills that prophecy, Ejogo proves Jane a capable woman with dreams and ambitions. She stands by her man, and, if anything, wants him to be able to stand without her propping him up. Jane becomes Baker’s crutch, something she refuses to be. Ejogo steals the show, and both her and Hawke have some genuinely sexy chemistry.

Though still hitting the familiar biopic beats, Born to Be Blue takes the route of acknowledging the biopics inherent narrative constructs – how things aren’t necessarily authentic and driven by cinematic effects – which allows the audience to come at this as untainted by past notions as possible. Hawke and Ejogo are utterly amazing, eschewing performances for something more lived-in and relatable. Chet Baker was the “James Dean of jazz,” and the film effortlessly skates on that and showing us what happened when James Dean was no more.