It’s difficult to put a modern film-fan in the mind of a viewer from the past, because of the nature of the medium. Editing and compositional techniques that were once avant-garde become incorporated into the language of cinema so quickly that it can be hard to appreciate how mold-breaking films could be, since the most effective techniques of the vanguard rapidly become the de riguer filmmaking of the commercial set. Jump cuts and non-linear narrative used to be wildly experimental – just a decade later they’re regularly used in network television, the most staid and crowd-friendly of visual entertainment.

This is true of much of western New Wave cinema, which saw its techniques (when they were effective) almost immediately grasped by Hollywood cinema. But cinema is a worldwide art form, and there’s a lot more to it than American commercial and European art movies. Viewing the new wave, ground-breaking techniques of movie-making from other cultures can still approximate, I think, the jolt of the new that the European New Wave injected in the ’60s into American cinema, because it is still weird and unfamiliar to Western eyes.

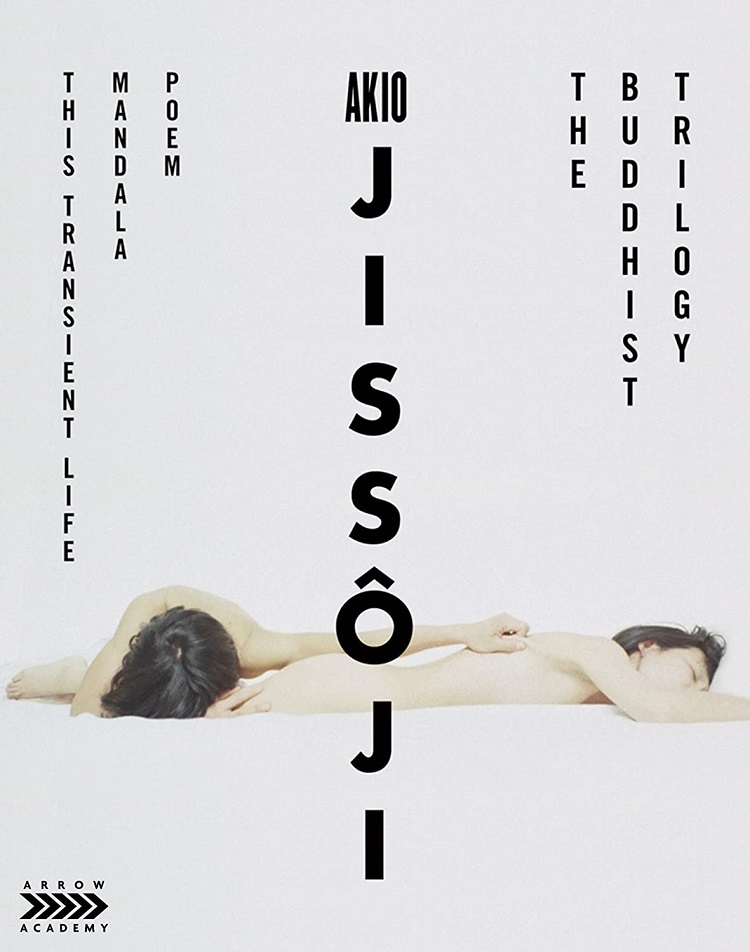

On several levels, Akio Jissoji: The Buddhist Trilogy exemplifies this kind of exhilarating newness, because it neither looks nor plays out like anything that American cinematic culture has subsumed into its maw of commercial-content ingestion and regurgitation. More than 40 years old, these films have a freshness to them and a raw excitement to their creation that can make them fascinating to watch.

Fascination is not the same thing as entertainment, though, and as interesting as they are to the cineaste, they might be overly perplexing, odd, or just plain incomprehensible to a general audience. And that’s even taking into account that every movie in this box set has copious, semi-graphic sex scenes with plenty of female nudity.

Akio Jissoji would, given his history prior to this trilogy of films (This Transient Life, Mandala, and Poem) seem as far as possible from an avant-garde art house director. His major credit before these films (and after, since he still worked in television) was being a major director of the Ultraman TV series, one of the original Kaiju-styled television series made in the wake of the success of Godzilla. “Tokukatsu” is the name of the style of film-making, meaning films made heavily from special effects.

The three (actually four, since there is another film included as a bonus feature) films of this box set are as far removed from that kind of crowd-pleasing action as possible. This Transient Life, made in 1970, is a strange stark tale of a man who lives completely with his own sense of morality. This sense includes happily beginning an incestuous relationship with his sister, eventually producing a child, and then engaging in an equally transgressive relationship with his mentor’s wife, eventually folding the mentor into it in a menage a trois scenario which thankfully is more talked about than shown on screen.

Masao, the transgressor in question, first semi-rapes his sister, Yuri, but in the tradition of much Japanese erotica, she eventually gets into it and welcomes his aggressive sexual attention. When she becomes pregnant, they cajole a servant boy who is infatuated with Yuri into taking credit for the child. Their incest doesn’t stop there, and they are spied on at various times by two men infatuated with Yuri – the servant boy, and the local Buddhist priest, who himself has lusted after Yuri from time to time.

Time is one of the things that this film plays with – years can pass by from a simple title card, but how much time is taken up is a mystery, as it the motivation of the characters themselves. Masao is a wicked protagonist, who despite being seeped in a selfish nihilism is consumed with the creation of Buddhist statues. He eventually becomes the student of a master carver, the mentor whose wife he eventually gets into a relationship with, though with her aggressive sexuality the question of who seduces who is wide open. The master’s son becomes aware of the relationship, and denounces it to the priest – but his motivation might be bred more from his lust for the father’s second wife than his disgust at Masao’s behavior.

Masao is a Dionysian figure, rejecting all aspects of Japanese traditional culture, and causing a wake of personal destruction in his path. But he never reconsiders his actions, and one of the central scenes of the film is his confrontation with the priest. The priest thinks Masao is some kind of demon; Masao believes he is a free spirit, and the only problems he causes arise from the hypocrisy of society.

It’s the most straightforward narrative of the three films, and perhaps the easiest to interpret, thought whether Masao is a force for destruction or of exhilarating release is left to the audience to determine. Shot in black and white, of the three films in this box-set This Transient Life seems to be the purest distillation of the director’s style. New Wave film-making embraced not only unconventional narratives, but also the breaking apart of the conventional forms of narrative film-making and the language of cinema. Compositions that would have gotten an American cinematographer fired on day one are the goal of this sort of film, and Jissoji is masterful at finding unconventional framing and camera movement strategies that also tell his particular stories.

The most common motif is occlusion: in several set-ups throughout the film most of the frame is blocked or left black except for the specific piece of information the director wants you to see. It’s not a new strategy – blacking out all of the frame besides a specific point has been around since the silent era. But Jissoji pointedly frames objects in the scene so that they fill up, unfocused, most of the field of view leaving the focused object small, often in the corner. In what would be conventional conversation scenes, shot and reverse shots are often absurdly close, calling attention to the artifice of the traditional cinematic language. Framing characters anywhere but at the center of the shot is another of the unconventional techniques that are regularly employed through all three films.

While both This Transient Life and Poem are shot in black and white, Mandala is a color feature film – though its use of color is so stark that it hardly seems in color while you’re watching it. The opening scene of this film is nothing less than relatively artfully shot soft core pornography, a vision of two bodies intertwined which has nearly nothing to do with real sex, but looks pretty fun.

But while there’s plenty of sex and nudity in these three films to fulfill the expectations of the soft-core market, the scenes are often undercut by the narrative. In This Transient Life, the incest brings the nausea. In Mandala, once the sex scene is over (right at the end of the opening credits) the woman talks about how hollow and empty it was.

She’s part of a partner swap, which she immediately regrets. The man, Shinichi, largely a nihilist, doesn’t understand what she’s so hung up on, since everything is meaningless anyway. The tryst takes place in a strange hotel that has apparently been rigged up for closed-circuit TV by Maki, a voyeur who turns out to be a cult leader with an extremely unorthodox recruitment method – he sends out two goons to follow Shinichi and his wife Yukiko onto the beach, knock him on the head, strip her naked and presumably rape her.

So, of course, Shinichi and Yukiko decide to check out the cult, since they seem to have it altogether. There isn’t much of a plot to the film, but rather a contrast of viewpoints between the two men in the partner swap. Shinichi gets into Maki’s philosophy of a return to primitivism through agriculture, rituals, and rape. The other man, Hirochi, visits the cult but is turned off by its collectivism – he’s a student who’d recently been run off campus by a communist student group who later hunt him down for betrayal of their collectivist ideals.

Shot in grainy color, interspersed with black and white, Mandala is as stylistically extreme in composition and camera movements as This Transient Life, and nearly as extreme in length. It was part of the rejection of rules that governed the production of these films: unconventional stories, filmmaking styles, and for the time uncommercial lengths: This Transient Life last 2 hours and 20 minutes, Mandala is 2 hours and 13. The theatrical cut of the third film, Poem, is under two hours, but the Blu-ray includes a director’s cut that tops out at 2 hours and 16 minutes. Deliberate pacing is another feature: these films make you work for them.

That’s particularly true of the conclusion to the trilogy, Poem. Opening with opaque shots of water running on stones, this black and white feature is about the Moriyama family, and their extraordinarily dedicated house boy Jun. He was sent to help with Yasushi’s law office, and is obsessive in his diligence. Every day he goes to the office from 9 to 5, and every night, bizarrely, he wakes up at midnight to patrol outside the house with a flashlight, in case there’s a fire.

The goings on in the Moriyama family are dysfunctional – Yasushi is a coward who wants to modernize his house, but is afraid to ask his father if he can do it. His wife Natsuko is undersexed, while his maid and law clerk are oversexed, but in secret, since their relationship would make Yasushi’s office lose reputation. Throughout it all Jun never wavers. When there’s an important case and Yasushi needs to work through the night, Jun leaves the office at 5 and cannot be persuaded to return. His devotion to his routine is total, and baffling, especially to the people he’s apparently devoted to.

These films are called The Buddhist Trilogy and some aspect of Buddhism is central to each story: In The Transient Life, Masao is training to make Buddhist statues. Jun in Poem traces the calligraphy on grave stones in a cemetery to learn calligraphy, and visits with the monk there. And while each film is deliberately obscure, and nuanced enough to be open to interpretation, I would say the general feeling is critical. Without spoiling the ends (though with these kinds of film spoilers seem almost beside the point) nothing good seems to happen to anybody involved with Buddhism, and the only hints of real transcendence come to a character who is one of the least sympathetic in the trilogy.

Akio Jissoji directed these films for the Art Theater Guild, a distributor and eventually a production company that was dedicated to bringing independent Japanese films into theaters. A number of important Japanese directors, such as Imamura and Oshima, worked with the ATG to create convention-challenging films. The Buddhist trilogy is certainly that: three very difficult films that demand, and reward close attention, even while contemplating and depicting repellent subjects like rape and incest, all within the context of critiques of Buddhist principles. That’s the sort of thing that appeals to a pretty limited, self-selecting audience. All of these films were intriguing, and provoking. I don’t know that they would fit many people’s definition of fun, though.

Akio Jissoji: The Buddhist Trilogy has been released by Arrow Academy on Blu-ray. Each film in the trilogy has an introduction and screen-specific commentaries by film professor David Dresser. There isn’t a commentary track over the entire film, but through several scenes, available through its own menu on the Blu-ray. Dresser is an amiable and informative guide through these very challenging films, pointing out cultural and cinematic aspects of the productions that can be easily overlooked by a befuddled viewer just trying to follow the story. The box set also has a booklet with essays on each film in the trilogy and one on Akio Jissoji’s place in Japanese film history.

There is also a fourth film in this package, It Was A Faint Dream, which is outside of the trilogy, though it shares similarities to the other films. First, it’s opaque as hell – maybe my mind was numbed by so much Jissoji in a short time, but I was maybe an hour into the film before I could discern who the story was about, and what relationship any character had to any other (and who knows? I might have it wrong.) Set in the 14th century among the various noble of the Japanese empire, it seems to be about the irresistible Shijo, who is forced to give up her child so she doesn’t disgrace her husband, who is not the child’s father. Of all of these films it has the most sympathetic lead, and is the only one to focus on a female protagonist. It does not have an introduction or commentary by Dresser or an essay in the booklet, but it sure would have come in handy.